Yams and sweet potatoes are completely different plants: true yams (Dioscorea genus) are starchy, dry tubers native to Africa and Asia with rough, bark-like skin, while sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) are sweeter, moister vegetables with smooth skin native to the Americas. In the United States, what's labeled as “yam” is almost always a variety of sweet potato.

Ever stood in the grocery store confused by the “yams” and “sweet potatoes” side by side? You're not alone. This common kitchen conundrum has persisted for decades, leaving shoppers wondering if they're buying two different vegetables or just one with multiple identities. Let's clear up this culinary confusion once and for all.

The Great Yam-Sweet Potato Mix-Up: What You Need to Know

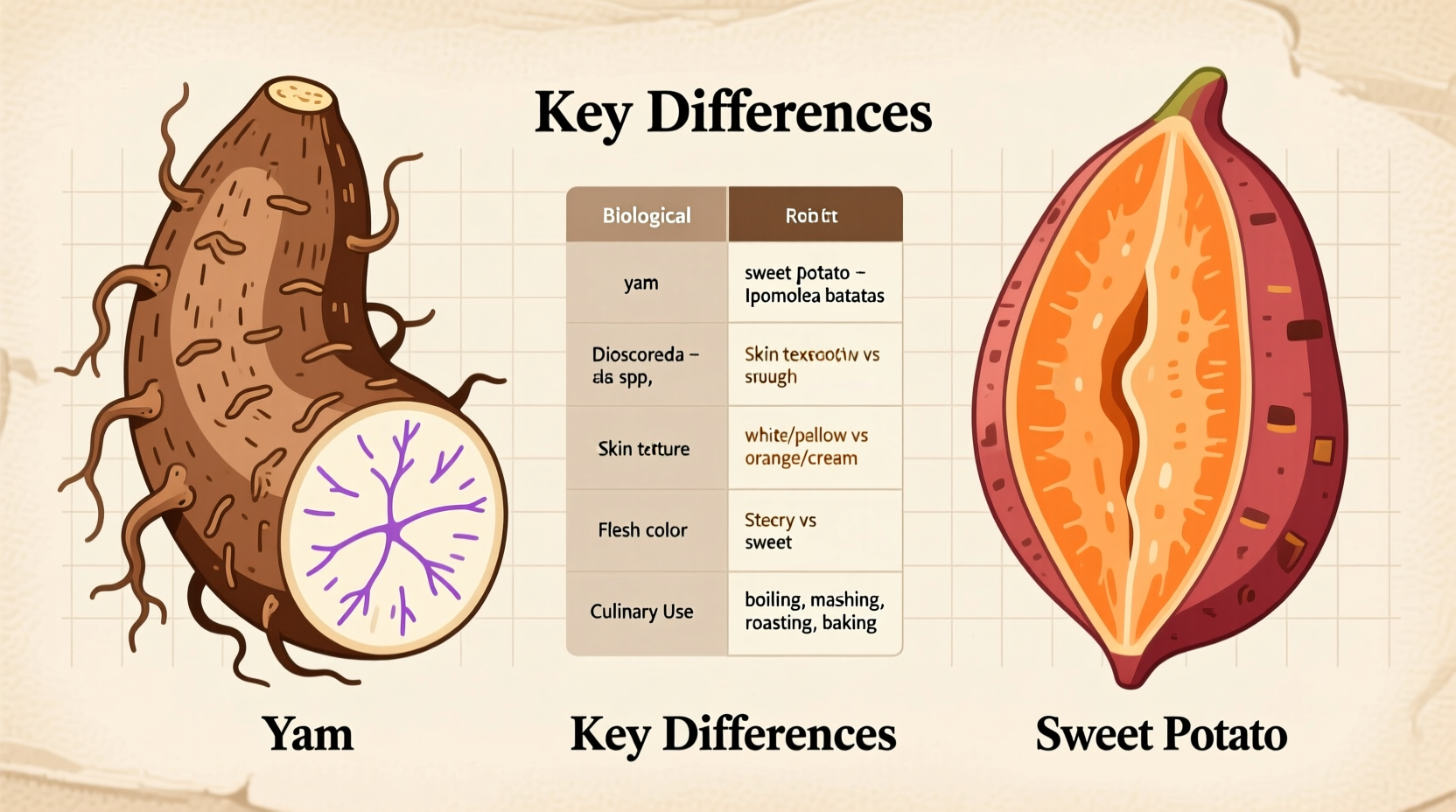

Despite what grocery store labels suggest, yams and sweet potatoes belong to entirely different plant families. True yams (Dioscorea genus) originate from Africa and Asia and feature rough, bark-like skin with white, purple, or reddish flesh. Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) come from the Americas, have smoother skin, and contain beta-carotene-rich orange flesh (though varieties exist with white or purple flesh).

The confusion began in the United States when soft varieties of sweet potatoes entered the market. To distinguish them from firmer sweet potatoes, producers started calling them “yams”—borrowing a term from West African languages (nyami or dhame) that describes true yams. The U.S. Department of Agriculture now requires that any product labeled “yam” must also include “sweet potato” to avoid consumer deception.

Spot the Difference: Visual Identification Guide

When shopping, these visual cues help distinguish between the two (though remember, true yams are rare in standard U.S. grocery stores):

| Characteristic | True Yam | Sweet Potato |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Family | Dioscoreaceae | Convolvulaceae (morning glory family) |

| Skin Texture | Rough, scaly, bark-like | Smooth, thin |

| Flesh Color | White, purple, or reddish | Orange, white, or purple |

| Taste | Starchy, neutral, less sweet | Naturally sweet, especially when cooked |

| Availability in US | Rare (specialty/international markets) | Widely available (all labeled “yams” are sweet potatoes) |

Why the Confusion Persists: A Historical Timeline

The mislabeling didn't happen overnight. Here's how this culinary identity crisis evolved:

- Pre-1930s: Two distinct sweet potato varieties existed in the U.S.—firm and soft—but both were called sweet potatoes

- 1930s: Southern producers began marketing soft sweet potatoes as “yams” to distinguish them from firm varieties, borrowing West African terminology

- 1953: The Louisiana Sweet Potato Commission formalized the practice to differentiate their moist-fleshed varieties

- Today: USDA regulations require “sweet potato” to appear alongside “yam” labeling, but the misnomer persists in grocery stores nationwide

Nutritional Comparison: Health Benefits Compared

While both provide valuable nutrients, sweet potatoes (the ones you're actually buying) offer distinct nutritional advantages. According to USDA FoodData Central:

- Sweet potatoes contain significantly more beta-carotene (which converts to vitamin A), providing over 400% of your daily value in one medium potato

- True yams have higher starch content and more potassium, but less vitamin A

- Both are excellent sources of fiber, vitamin C, and manganese

- Sweet potatoes have a lower glycemic index than white potatoes but higher than true yams

Practical Shopping Guide: What You're Really Buying

When navigating produce aisles in North America or Europe, keep these practical tips in mind:

- Orange-fleshed varieties labeled “yams” are always sweet potatoes (usually Jewel or Beauregard varieties)

- True yams have blackish-brown, scaly skin and off-white flesh—you'll typically find them in African or Caribbean specialty markets

- White-fleshed sweet potatoes (sometimes called “Japanese yams”) are still sweet potatoes, not true yams

- When recipes call for yams, they almost always mean orange sweet potatoes—use them interchangeably

Culinary Applications: Best Uses for Each

Understanding the difference matters for cooking results:

- Sweet potatoes (orange-fleshed) work best for roasting, mashing, and baking due to their natural sweetness and moist texture

- White-fleshed sweet potatoes hold their shape better for soups and stews

- True yams require longer cooking times and work well in African and Asian stews where their neutral flavor absorbs other ingredients

- For Thanksgiving dishes, any “yam” labeled product will work perfectly for casseroles and pies

Global Perspectives: What's Called What Around the World

The naming confusion varies significantly by region:

- In Nigeria (the world's largest yam producer), “yam” always refers to true yams, while sweet potatoes have different local names

- European markets typically use “sweet potato” exclusively, avoiding “yam” labeling

- Caribbean countries often distinguish between “yam” (true yam) and “sweet potato” or “batata”

- Australian markets use “sweet potato” for orange varieties and “ube” or “oca” for true yams

Common Misconceptions Debunked

Let's address some persistent myths:

- Myth: Yams are just a darker variety of sweet potato

Truth: They're botanically unrelated plants from different continents - Myth: The terms are interchangeable worldwide

Truth: Outside North America, “yam” almost always means the true yam - Myth: Sweet potatoes labeled as yams are genetically modified

Truth: They're naturally occurring varieties—no GMOs involved

Practical Takeaways for Your Next Grocery Trip

Now that you understand the difference, here's how to apply this knowledge:

- Don't worry about finding “real” yams for standard recipes—what's labeled as yams will work perfectly

- For authentic African or Asian dishes requiring true yams, visit specialty international markets

- When following international recipes, check whether they specify true yams or sweet potatoes

- Store both types in a cool, dark place (not the refrigerator) for optimal shelf life

FAQs About Yams vs Sweet Potatoes

Are yams and sweet potatoes the same thing?

No, they are completely different plants from unrelated botanical families. What's labeled as “yams” in U.S. grocery stores are actually sweet potatoes—a mislabeling practice that began in the 1930s to distinguish soft sweet potato varieties from firm ones.

Why does my grocery store call sweet potatoes yams?

This labeling practice started in the 1930s when soft-fleshed sweet potatoes entered the market. Producers began calling them “yams” (borrowing from West African terminology) to distinguish them from firmer sweet potato varieties. The USDA now requires that any product labeled “yam” must also include “sweet potato” to avoid consumer confusion.

How can I tell if I'm buying a real yam?

True yams have rough, scaly, bark-like skin that's difficult to peel, with off-white to purple flesh. They're rarely found in standard U.S. grocery stores—look for them in African, Caribbean, or Asian specialty markets. If the skin is smooth and the flesh is orange, you're definitely buying a sweet potato, regardless of what the label says.

Which is healthier, yams or sweet potatoes?

Both offer nutritional benefits, but sweet potatoes (what you're actually buying in the U.S.) contain significantly more beta-carotene (which converts to vitamin A), providing over 400% of your daily value in one medium potato. True yams have higher starch content and more potassium, but less vitamin A. Both are excellent sources of fiber, vitamin C, and manganese.

Can I substitute yams for sweet potatoes in recipes?

In North America, you don't need to substitute because what's labeled as “yams” are actually sweet potatoes. For recipes calling for true yams (common in African or Asian cuisine), sweet potatoes won't work as a direct substitute due to texture and flavor differences—true yams are starchier and less sweet. If you can't find true yams, consider using taro root or malanga as alternatives in authentic international dishes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4