Discover why fermented foods have sustained human civilizations for millennia and how they're revolutionizing modern nutrition. This guide delivers scientifically-backed insights you can trust, revealing exactly how fermentation transforms ordinary ingredients into nutritional powerhouses while addressing common safety concerns and practical usage tips.

The Science Behind Fermentation: Nature's Oldest Food Technology

Fermentation represents one of humanity's earliest food preservation techniques, harnessing beneficial microorganisms to transform raw ingredients. At its core, fermentation occurs when microbes like Lactobacillus bacteria or Saccharomyces yeast consume natural sugars in food, producing lactic acid, alcohol, or carbon dioxide as byproducts. This biological process creates the distinctive tangy flavors and textures we associate with fermented products while simultaneously preserving them.

Unlike spoilage—which involves harmful bacteria causing food deterioration—controlled fermentation encourages specific beneficial microbes to dominate, creating an environment where pathogens cannot survive. The resulting acidic conditions not only extend shelf life but also enhance nutritional value through biochemical transformations that increase vitamin content and break down anti-nutrients.

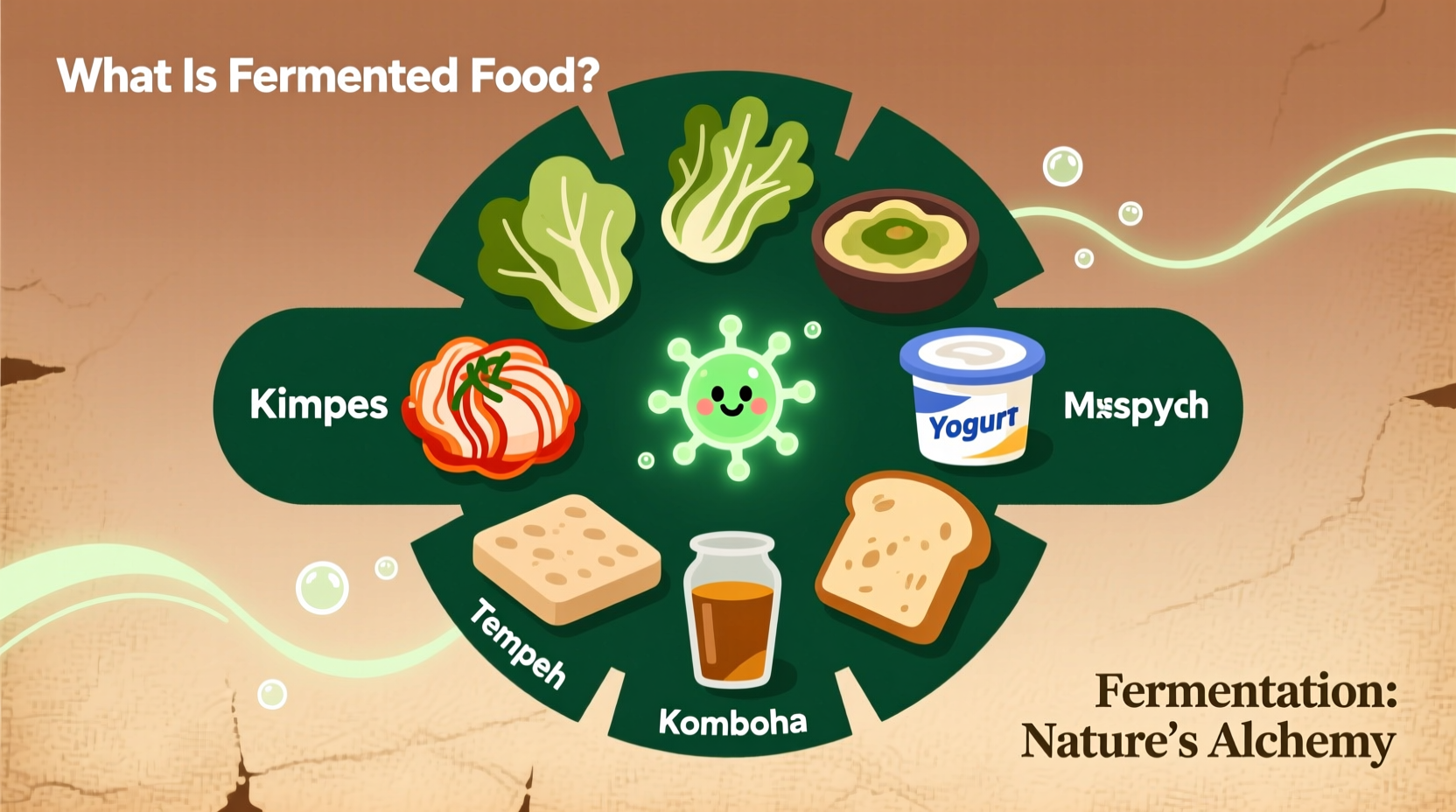

Global Fermented Food Categories: A Culinary World Tour

Fermentation practices have evolved uniquely across cultures, adapting to local ingredients and climate conditions. These traditional methods have created distinctive food categories that remain dietary staples worldwide.

| Category | Common Examples | Primary Microorganisms | Origin Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Ferments | Yogurt, kefir, cheese | Lactobacillus, Streptococcus | Middle East, Central Asia |

| Vegetable Ferments | Sauerkraut, kimchi, pickles | Lactobacillus plantarum | China, Europe, Korea |

| Grain-Based Ferments | Sourdough, injera, dosa | Lactic acid bacteria, wild yeast | Middle East, Africa, India |

| Soy Ferments | Miso, tempeh, soy sauce | Aspergillus oryzae, Rhizopus | China, Japan, Indonesia |

Evolution of Fermentation: From Ancient Preservation to Modern Science

The history of food fermentation spans thousands of years, evolving from accidental discoveries to precisely controlled processes:

- Prehistoric Era (10,000+ BCE): Early humans likely discovered fermentation accidentally when stored grains or fruits naturally fermented. Archaeological evidence shows fermented beverages existed in China as early as 7000 BCE.

- Ancient Civilizations (3000-500 BCE): Egyptians developed leavened bread, while Mesopotamians brewed beer. Chinese records document soy fermentation techniques dating to 300 BCE.

- Classical Period (500 BCE-500 CE): Romans perfected cheese making and wine production. Greek physician Hippocrates prescribed fermented foods for digestive ailments.

- Scientific Revolution (1857): Louis Pasteur identified yeast as the agent of fermentation, moving the process from folk tradition to scientific understanding.

- Modern Era (20th Century-Present): Development of starter cultures and controlled fermentation environments enabled consistent, safe production of fermented foods at scale.

This historical progression demonstrates how fermentation evolved from necessity to nutritional science, with recent research validating many traditional health claims through modern analytical methods.

Nutritional Transformation: Why Fermentation Boosts Food Value

Fermentation doesn't just preserve food—it fundamentally enhances its nutritional profile through several biochemical processes:

Microbial activity during fermentation increases bioavailability of nutrients by breaking down complex compounds. For example, the phytic acid in grains—which can inhibit mineral absorption—is significantly reduced during sourdough fermentation, making zinc and iron more accessible to the body. Similarly, the fermentation process in yogurt converts lactose into lactic acid, creating a more digestible product for lactose-intolerant individuals.

Research published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry confirms that kimchi fermentation increases levels of vitamins B and C while generating beneficial compounds like capsaicinoids and flavonoids. The same study documented how lactic acid bacteria in fermented vegetables produce enzymes that enhance the body's ability to utilize nutrients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognizes traditionally fermented foods as valuable sources of probiotics that support gut health. Unlike many commercial probiotic supplements, fermented foods deliver live microbes in their natural food matrix, potentially enhancing their survival through the digestive tract.

Safety Considerations: Identifying Quality Fermented Products

While properly fermented foods are remarkably safe due to the protective acidic environment they create, consumers should understand how to identify high-quality products:

- Visual indicators: Properly fermented vegetables should maintain their color without mold growth (except in specific traditional preparations like katsuobushi). Bubbling during active fermentation is normal, but slimy textures indicate spoilage.

- Smell test: Healthy fermentation produces pleasant sour or tangy aromas. Rotten, putrid, or alcoholic smells beyond expected levels suggest contamination.

- Storage requirements: Most fermented vegetables should be refrigerated after initial fermentation to slow the process. Products labeled "raw" or "unpasteurized" contain live cultures, while pasteurized versions do not.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides specific guidelines for safe home fermentation, emphasizing proper salt concentrations, clean equipment, and adequate submersion of vegetables in brine to prevent harmful bacterial growth. Commercial products must meet strict safety standards documented in the FDA's Fermented and Microbial Cultured Foods guidance.

Practical Integration: Adding Fermented Foods to Your Daily Diet

Incorporating fermented foods into your routine doesn't require dramatic changes. Start with these simple, sustainable approaches:

- Begin your day with ¼ cup of plain yogurt or kefir, which provides approximately 1-2 billion CFU (colony forming units) of beneficial bacteria.

- Add 2-3 tablespoons of sauerkraut or kimchi to sandwiches, salads, or grain bowls for tangy flavor and probiotic benefits.

- Replace regular vinegar with fermented alternatives like apple cider vinegar in dressings and marinades.

- Experiment with fermented condiments like miso paste, which adds umami depth to soups and sauces with just 1-2 teaspoons.

When selecting commercial products, look for "live and active cultures" on the label and avoid those with vinegar as the first ingredient, which indicates quick-pickled rather than traditionally fermented items. For best results, introduce fermented foods gradually to allow your digestive system to adjust to increased microbial activity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4