Processed food encompasses any food that has undergone changes from its natural state through methods like cooking, canning, freezing, or adding preservatives. The key distinction lies in the degree and purpose of processing—from minimally processed items like bagged spinach to ultra-processed products like soda and packaged snacks. Understanding what constitutes processed food helps consumers make informed dietary choices while recognizing that not all processing is inherently harmful.

When you search what constitutes processed food, you're likely trying to decipher confusing grocery labels or understand health recommendations. You deserve clear, science-based information—not oversimplified "good vs bad" narratives. This guide cuts through the noise with practical distinctions backed by food science experts, helping you identify processed foods in your pantry and make smarter choices without unnecessary fear.

Defining Food Processing: Beyond the Headlines

The term "processed food" often triggers negative assumptions, but processing itself isn't inherently problematic. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, food processing includes any method used to convert raw ingredients into food products. This spans centuries-old techniques like fermentation and modern industrial methods.

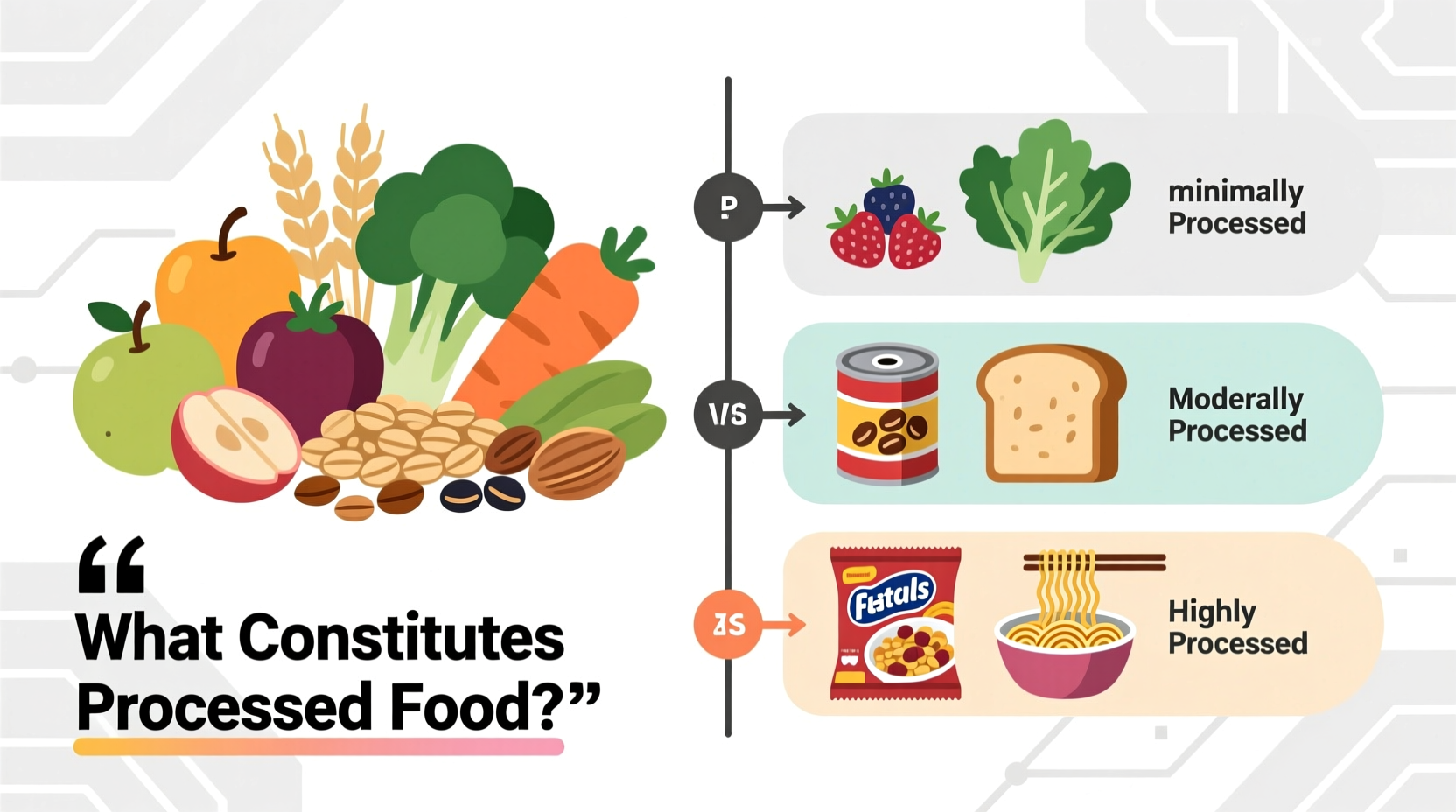

What matters is how much and why food is processed. The NOVA food classification system—developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo and now used globally—provides the most scientifically accepted framework. It categorizes foods based on processing extent rather than nutritional content alone:

| NOVA Category | Processing Level | Common Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Unprocessed/Minimally Processed | Fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, milk, dried beans | Altered only to extend shelf life (washing, freezing, pasteurization) |

| Group 2 | Processed Culinary Ingredients | Salt, sugar, oils, vinegar | Extracted from Group 1 foods for cooking |

| Group 3 | Processed Foods | Canned vegetables, cheese, freshly baked bread | Simple preservation methods; 2-3 ingredients |

| Group 4 | Ultra-Processed Foods | Soda, packaged snacks, ready-to-heat meals | Industrial formulations with 5+ ingredients; contain additives |

How Food Processing Evolved: A Historical Perspective

Food processing isn't a modern phenomenon—it's essential to human civilization. Understanding this timeline reveals why processing exists and how methods have changed:

- Prehistoric Era: Fire for cooking (improves digestibility and safety)

- Ancient Civilizations: Fermentation (yogurt, wine), drying (jerky), salting (preservation)

- 19th Century: Canning (Napoleonic Wars food preservation), pasteurization

- Early 20th Century: Freezing technology, hydrogenated oils

- Late 20th Century: Rise of ready-to-eat meals and food additives

- Today: High-pressure processing, flash freezing, clean-label movement

This historical context shows that processing primarily developed to solve real problems: prevent spoilage, improve safety, and increase food access. The shift toward ultra-processing emerged with industrialization, focusing on convenience and extended shelf life.

Identifying Processed Foods: Practical Detection Methods

Spotting processed foods requires looking beyond marketing claims. Here's how to analyze products like a food scientist:

Ingredient List Analysis

Check for these red flags indicating ultra-processing:

- More than 5 ingredients

- Unfamiliar chemical-sounding names (e.g., tertiary butylhydroquinone)

- Added sugars under multiple names (high-fructose corn syrup, maltodextrin)

- Artificial colors or flavors

Visual and Textural Clues

Ultra-processed foods often display these characteristics:

- Unnaturally uniform color/texture

- Excessive crispness or softness that doesn't match natural state

- Long ingredient lists where additives appear in the first third

When Processing Benefits Health (And When It Doesn't)

Not all processed foods deserve criticism. Context matters significantly:

Situations Where Processing Adds Value

- Pasteurization eliminates harmful pathogens in dairy

- Canning preserves seasonal produce year-round (e.g., tomatoes for winter sauces)

- Fortification adds nutrients (iodized salt prevents deficiency disorders)

- Freezing locks in nutrients shortly after harvest

Problematic Processing Scenarios

- Added sugars in 85% of packaged foods (American Heart Association)

- Trans fats from partial hydrogenation (now largely banned but legacy products exist)

- Nutrient stripping during refining (white flour vs. whole grain)

- Additives with uncertain long-term health effects

Making Smarter Choices: A Practical Framework

Instead of labeling all processed foods "bad," use this decision-making approach:

- Assess processing level using the NOVA categories

- Check ingredient count - aim for 5 or fewer recognizable items

- Evaluate added components - is sugar/oil/salt among first 3 ingredients?

- Consider nutritional density - does it provide meaningful nutrients per calorie?

- Question necessity - could you prepare this simply at home?

For example, plain Greek yogurt (Group 3) offers protein and probiotics with minimal processing, while fruit-flavored yogurt (Group 4) often contains added sugars and artificial colors. Both are processed, but their health impacts differ significantly.

Reading Between the Lines: Marketing vs. Reality

Food manufacturers use clever labeling to make processed foods appear healthier. Watch for these misleading tactics:

- "Natural" claims - legally undefined for most products

- "No artificial ingredients" - may still contain natural additives

- "Made with real fruit" - often means 2% fruit content

- Health halo effect - products marketed as "healthy" often compensate with added sugars

The USDA's Food and Nutrition Service recommends focusing on whole food ingredients rather than marketing claims when evaluating processed foods.

Building a Balanced Approach to Processed Foods

Complete avoidance of processed foods is unrealistic and unnecessary for most people. Instead, adopt these evidence-based strategies:

- Make Groups 1-3 foods 80% of your diet (per Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

- Use ultra-processed foods strategically for convenience during busy periods

- Learn simple home processing techniques (e.g., batch cooking, freezing)

- Read labels consistently—not just for calories but ingredient quality

Remember that processing exists on a spectrum. An apple is unprocessed, apple sauce is minimally processed, and apple-flavored candy is ultra-processed. The goal isn't elimination but informed selection based on your health goals and lifestyle.

Common Questions About Processed Foods

Is bread considered processed food?

Yes, most bread is processed (NOVA Group 3). Traditional bread requires flour, water, yeast, and salt—simple ingredients with minimal industrial processing. However, many commercial breads contain added sugars, preservatives, and dough conditioners that push them into Group 4 (ultra-processed). Look for breads with short ingredient lists and no added sweeteners for healthier options.

Are frozen vegetables processed?

Frozen vegetables are minimally processed (NOVA Group 1). They're typically blanched briefly then flash-frozen shortly after harvest, preserving nutrients better than some "fresh" produce that travels long distances. Unlike canned vegetables, they contain no added salt or sugar. Research from the University of California shows frozen produce often has comparable or higher nutrient levels than fresh counterparts sold weeks after harvest.

Does all processed food contain preservatives?

No. Many processed foods use natural preservation methods instead of chemical preservatives. Examples include: fermented foods like sauerkraut (acid preservation), dried fruits (moisture removal), and canned tomatoes (heat processing). Ultra-processed foods typically contain preservatives, but minimally processed items like frozen vegetables or vacuum-sealed roasted peppers often contain none.

How can I reduce ultra-processed foods without overhauling my diet?

Start with these manageable swaps: replace sugary breakfast cereals with plain oats, choose whole fruit instead of fruit snacks, swap soda for sparkling water with fresh citrus, and select plain yogurt instead of flavored varieties. The key is gradual replacement rather than elimination—research in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition shows small, consistent changes yield better long-term results than drastic overhauls.

Is organic processed food healthier?

Organic certification relates to farming methods, not processing level. An organic cookie still qualifies as ultra-processed if it contains multiple refined ingredients and additives. While organic options avoid synthetic pesticides and GMOs, they can still be high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats. Focus first on processing level (NOVA category), then consider organic status as a secondary factor for the foods you regularly consume.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4