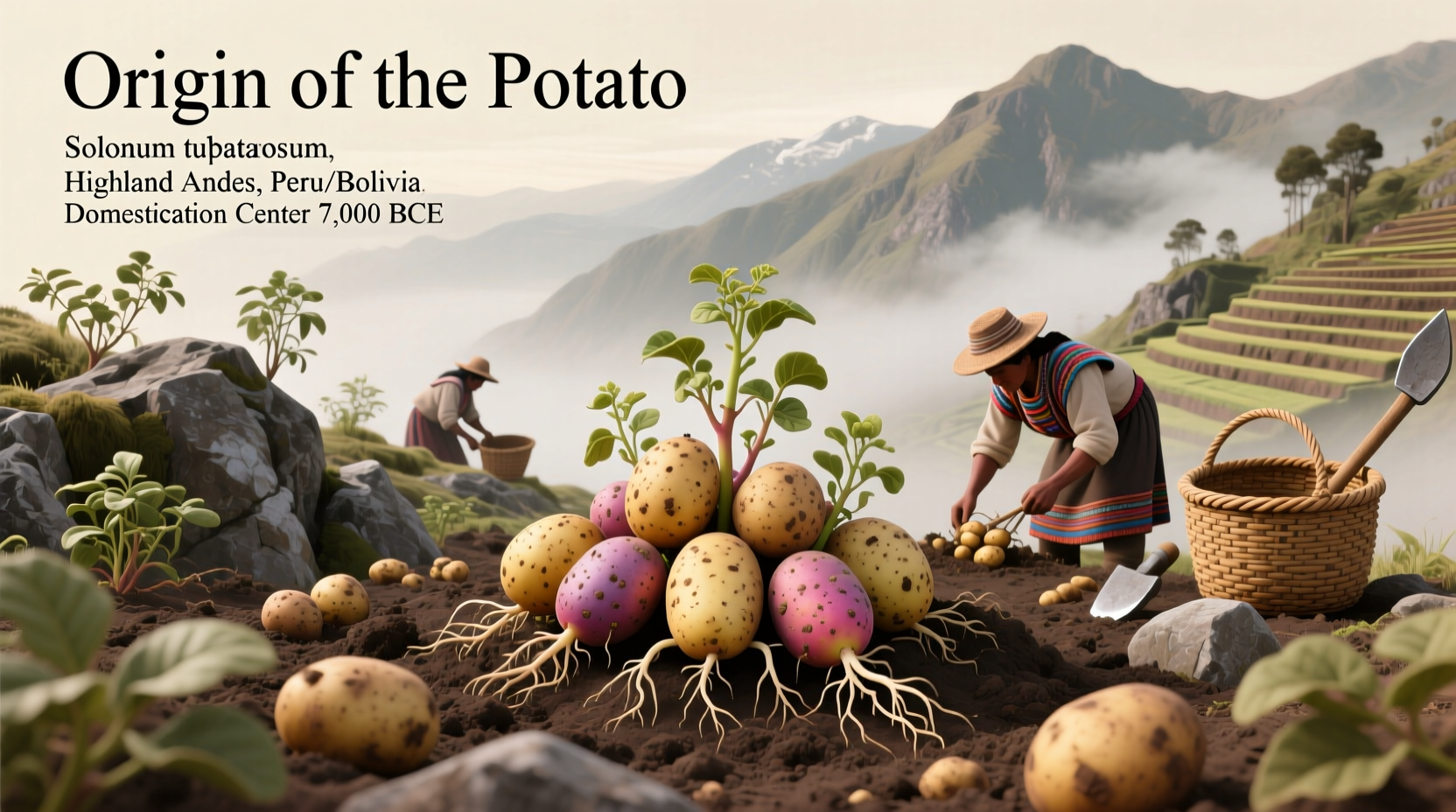

For centuries, the humble potato has been a dietary staple across the globe, but its journey began in one of Earth's most challenging environments. Understanding where potatoes originated isn't just a historical curiosity—it reveals how this resilient crop transformed from an obscure Andean tuber into one of humanity's most important food sources.

The Andean Birthplace of Potatoes

Archaeological evidence confirms that ancient peoples in the Andes Mountains first cultivated potatoes between 8,000 and 5,000 BCE. The Titicaca Basin, straddling modern-day Peru and Bolivia at elevations over 12,000 feet, provided the perfect conditions for early potato domestication. This harsh environment—characterized by freezing nights, intense sunlight, and thin soil—shaped the potato's remarkable genetic diversity and hardiness.

Researchers from the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru have identified over 4,000 native potato varieties still grown in the Andes today. These traditional varieties demonstrate incredible adaptations to different microclimates, soil types, and elevation ranges. The Quechua and Aymara peoples developed sophisticated agricultural techniques to cultivate potatoes in this challenging terrain, including:

- Freeze-drying potatoes to create chuño (a preservation method still used today)

- Developing terrace farming systems to maximize arable land

- Creating complex crop rotation systems to maintain soil fertility

Scientific Evidence of Potato Origins

Modern genetic research has pinpointed the exact origin of cultivated potatoes. A landmark study published in Nature Genetics analyzed the DNA of hundreds of potato varieties and confirmed that all modern potatoes trace back to a single domestication event in southern Peru near Lake Titicaca.

| Site | Location | Estimated Date | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tres Ventanas Cave | Peru | 2500 BCE | Oldest known potato remains found in archaeological context |

| Chilca Canyon | Peru | 2000 BCE | Evidence of early potato preservation techniques |

| Chiripa Settlement | Bolivia | 1500 BCE | Advanced potato storage systems discovered |

| Moche Culture Sites | Peru | 100-800 CE | Potato imagery in pottery and textiles |

The Journey from Andes to Global Staple

For thousands of years, potatoes remained exclusive to the Andean region until Spanish conquistadors encountered them in the 16th century. The first recorded introduction of potatoes to Europe occurred in 1570 when Spanish sailors brought them back from Peru. Initially met with suspicion, potatoes gradually gained acceptance across Europe through these key developments:

- 1585: First documented potato cultivation in Spain

- 1600s: Adoption by Irish farmers as a reliable crop

- 1700s: Promotion by European monarchs like Frederick the Great of Prussia

- 1795: Antoine-Augustin Parmentier's famous potato banquet for French nobility

By the 19th century, potatoes had become a dietary staple across Europe, though this dependence also led to the devastating Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852) when a potato blight destroyed crops. This tragedy underscored both the potato's importance to global food security and the dangers of relying on limited genetic diversity.

Why Potato Origins Matter Today

Understanding where potatoes originated isn't merely historical—it has profound implications for modern agriculture and food security. The native potato varieties still grown in the Andes represent a crucial genetic reservoir for developing disease-resistant, climate-resilient potato strains. As climate change threatens global food systems, researchers increasingly turn to these ancient varieties for solutions.

The International Potato Center maintains the world's largest collection of potato diversity, with over 7,000 accessions from 108 countries. Scientists regularly travel to Andean communities to collect traditional varieties that might contain genes for:

- Drought tolerance

- Pest and disease resistance

- Nutritional enhancement

- Adaptation to changing climate conditions

Modern Potato Production and Diversity

Today, China leads global potato production, followed by India and Ukraine. However, the greatest genetic diversity remains concentrated in the Andes, where indigenous farmers continue to cultivate hundreds of native varieties using traditional methods passed down through generations.

While commercial agriculture has narrowed potato varieties to just a few types (Russet, Yukon Gold, Red Bliss), the original Andean diversity offers solutions to modern agricultural challenges. Researchers have discovered that many native varieties contain higher levels of nutrients like iron and zinc compared to commercial varieties—a critical consideration for addressing malnutrition worldwide.

Preserving Potato Heritage

Efforts to preserve potato biodiversity face significant challenges as traditional farming practices decline and climate change alters growing conditions in the Andes. Organizations like the International Potato Center work with Andean communities to:

- Document traditional knowledge about potato cultivation

- Create community seed banks to preserve native varieties

- Develop markets for native potatoes to support farmer livelihoods

- Integrate traditional knowledge with modern agricultural science

This work recognizes that preserving potato diversity isn't just about maintaining historical artifacts—it's about safeguarding genetic resources essential for feeding a growing global population in an era of climate uncertainty.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4