Ever stood in the grocery store produce section, confused by labels calling orange-fleshed vegetables “yams” when you thought yams were something completely different? You're not alone. This widespread confusion affects millions of shoppers who want to make informed choices about these nutritious root vegetables. Let's clear up the misconception once and for all with scientifically accurate information you can trust.

Why the Sweet Potato vs. Yam Confusion Exists

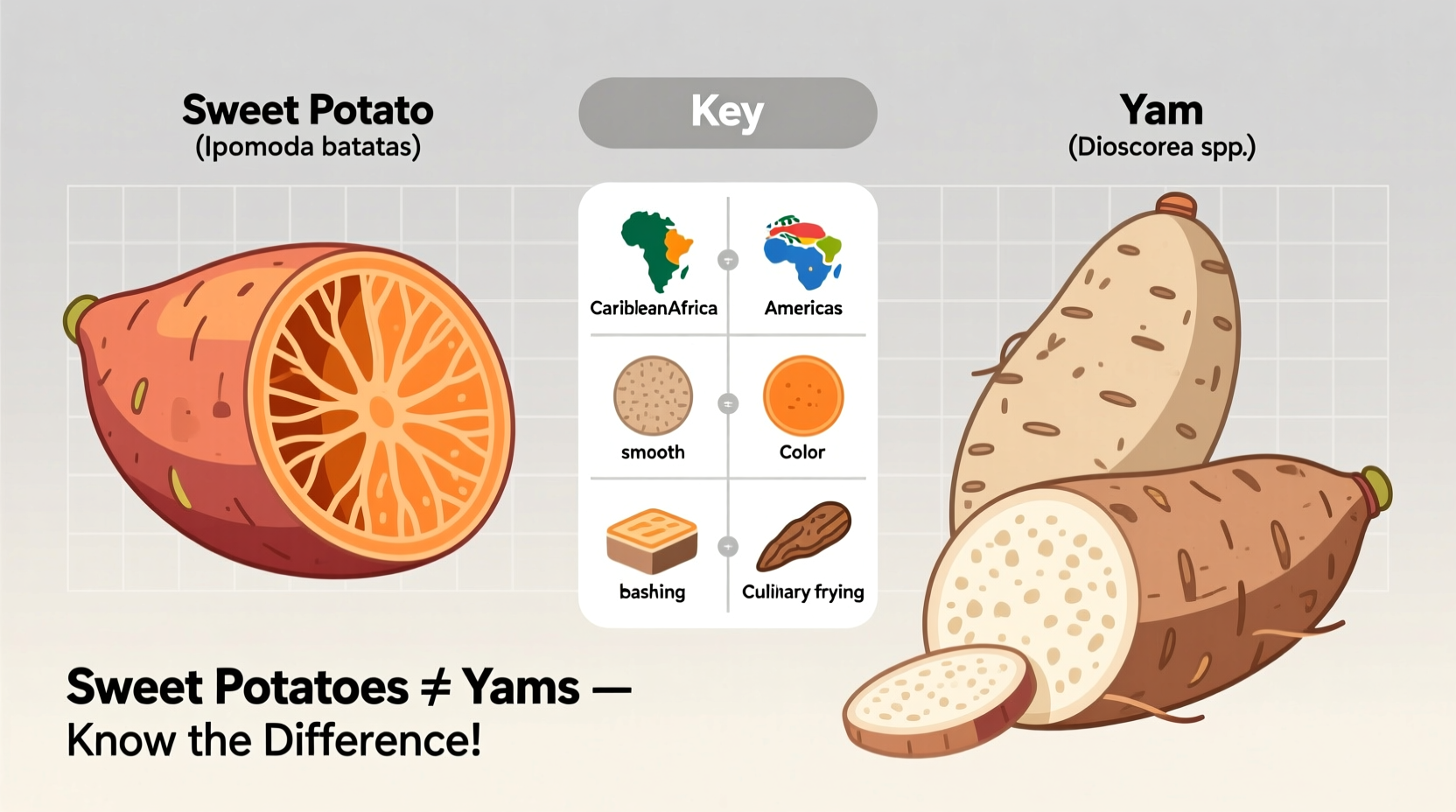

The mix-up between sweet potatoes and yams primarily stems from American marketing practices. When orange-fleshed sweet potatoes were introduced commercially in the 1930s, producers needed to distinguish them from the traditional white-fleshed sweet potatoes already in the market. They began using the African word “yam” (pronounced “yahm”), which refers to a completely different tuber, to describe these new orange varieties. This marketing strategy stuck, despite being botanically incorrect.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, all products labeled as “yams” in the U.S. must also include the term “sweet potato” to avoid consumer confusion. This regulation exists because true yams are rarely found in standard American grocery stores—you'll typically need to visit specialty international markets to find them.

Botanical Differences: Not Just Marketing Hype

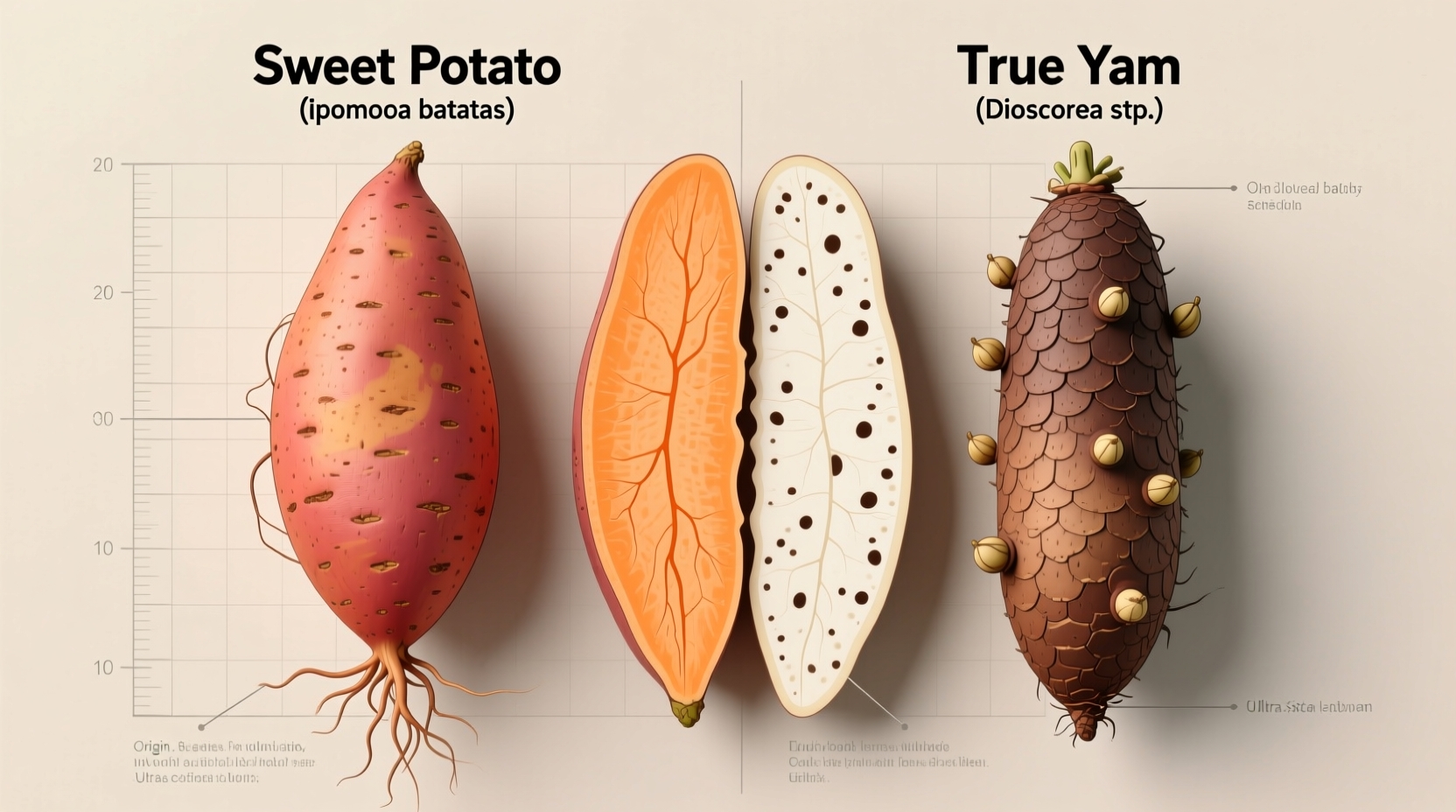

Understanding the fundamental botanical differences explains why these vegetables shouldn't be used interchangeably in recipes:

| Characteristic | Sweet Potato | True Yam |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Classification | Ipomoea batatas (morning glory family) | Dioscorea species (yam family) |

| Origin | Central and South America | West Africa and Asia |

| Skin Texture | Thin, smooth, often reddish-brown | Thick, rough, bark-like, blackish-brown |

| Flesh Color | Orange, white, purple, or yellow | White, yellow, or purple (rarely orange) |

| Taste Profile | Naturally sweet, moist | Starchy, dry, neutral flavor |

| Nutritional Profile | Higher in beta-carotene (vitamin A), vitamin C | Higher in potassium, fiber |

This factual comparison shows why substituting one for the other can dramatically affect your cooking results. Sweet potatoes contain up to 100% of your daily vitamin A needs in just one serving, while true yams provide more complex carbohydrates that release energy slowly.

How to Identify What's in Your Grocery Store

When shopping in North America or Europe, what's labeled as “yams” are almost certainly sweet potatoes. Here's how to tell what you're actually getting:

- Orange-fleshed varieties (often mislabeled as yams): These include Jewel, Garnet, and Beauregard varieties with copper skin and deep orange flesh

- White-fleshed sweet potatoes: Sometimes called “soft” varieties with tan skin and pale flesh

- True yams: Only found in specialty international markets, with black, bark-like skin and white or yellow flesh

Nutritional Comparison: Health Benefits Explained

While both provide valuable nutrients, their nutritional profiles differ significantly. According to USDA FoodData Central, a medium sweet potato (130g) contains:

- 400% of your daily vitamin A needs (as beta-carotene)

- 35% of your daily vitamin C

- 15% of your daily fiber needs

- Only 112 calories

True yams, by comparison, contain less vitamin A but more potassium and resistant starch, which supports gut health. The orange color in sweet potatoes comes from beta-carotene, which your body converts to vitamin A—a nutrient virtually absent in true yams.

Culinary Applications: When Substitution Works (and When It Doesn't)

Understanding these differences helps you make better cooking decisions:

Sweet potatoes work best when: You want natural sweetness and moist texture—perfect for roasting, mashing, or baking into pies. Their high sugar content causes caramelization that enhances roasted dishes.

True yams work best when: You need a neutral, starchy base that holds its shape—ideal for soups, stews, or dishes where you want the tuber to maintain firmness after cooking. In West African and Caribbean cuisines, yams are often boiled, fried, or pounded into fufu.

Professional chefs note that substituting true yams for sweet potatoes in desserts usually fails because of the significant moisture and sugar differences. However, in savory applications like soups, substitution might work with recipe adjustments.

Shopping and Storage Guide

Now that you can identify what's what, here's how to select and store these tubers properly:

- Selection: Choose firm specimens without soft spots, bruises, or signs of sprouting. Sweet potatoes should feel heavy for their size.

- Storage: Keep in a cool, dark, well-ventilated place (not the refrigerator). Properly stored sweet potatoes last 3-5 weeks; true yams can last up to a month.

- Preparation tip: Sweet potatoes oxidize quickly when cut—place in cold water until ready to cook to prevent discoloration.

Remember that refrigeration causes sweet potatoes to develop a hard center and unpleasant flavor. The ideal storage temperature is between 55-60°F (13-15°C)—much warmer than your standard refrigerator.

Global Perspectives on These Tubers

The confusion between sweet potatoes and yams highlights how food terminology varies globally. In West Africa, where true yams are a dietary staple, the word “yam” refers exclusively to Dioscorea species. Meanwhile, in Japan, what Americans call sweet potatoes are known as “satsumaimo,” while true yams are “jinenjo.” This linguistic variation explains why travelers often experience confusion when encountering these vegetables abroad.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4