Ever wonder why your grocery list includes items that don't grow on trees or in fields? Understanding processed foods isn't just about reading labels—it's about making empowered choices that align with your health goals. In this guide, you'll discover how to distinguish between beneficial processing techniques and problematic additives, backed by nutritional science rather than food fads.

The Processing Spectrum: From Farm to Fork

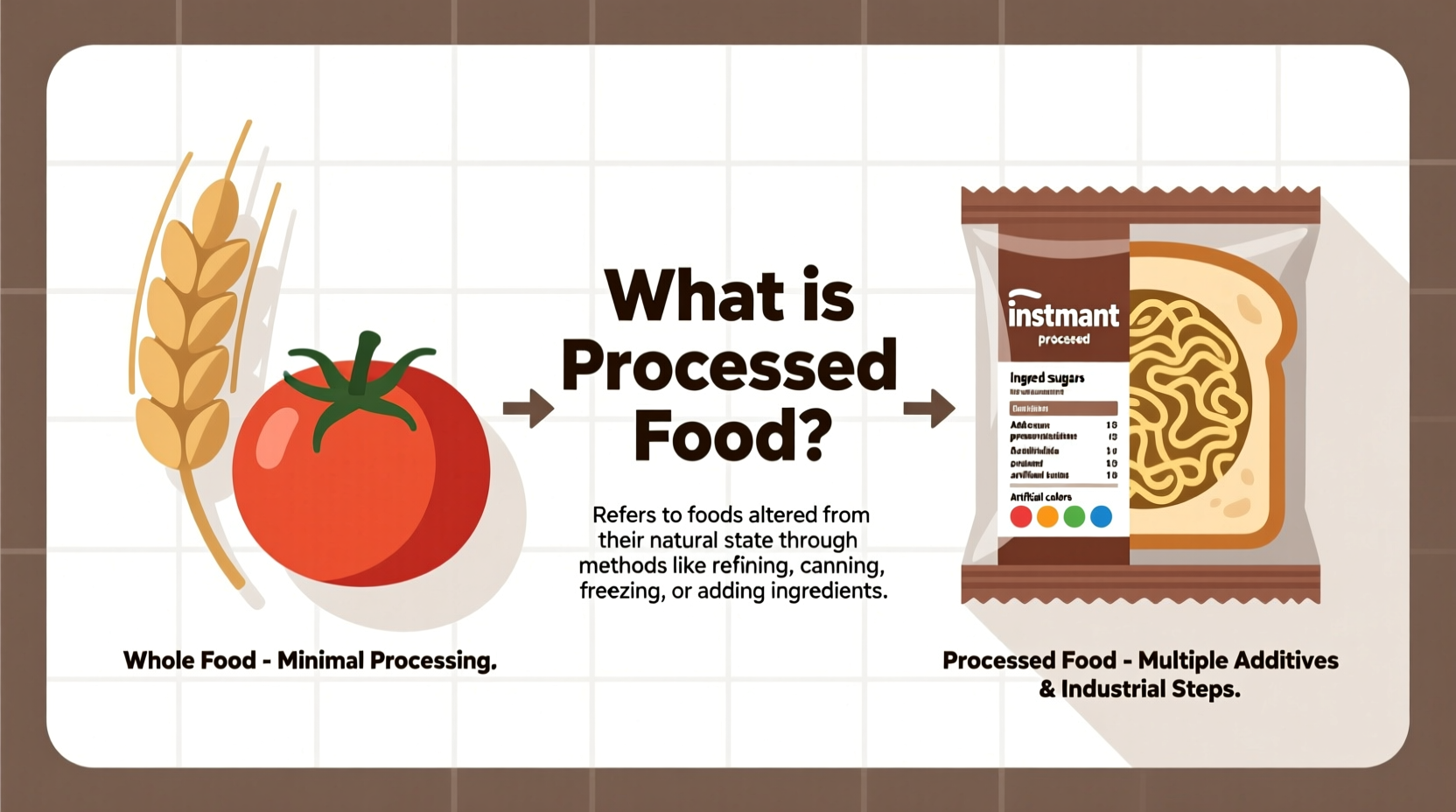

Food processing exists on a continuum, not as a simple "good vs bad" dichotomy. The NOVA food classification system, developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo and endorsed by the World Health Organization, categorizes foods by the extent and purpose of processing:

| Processing Level | Definition | Common Examples | Nutritional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unprocessed/Minimally Processed | Whole foods altered by washing, freezing, or pasteurization | Fresh produce, dried herbs, roasted nuts | Maintains natural nutrient profile |

| Culinary Ingredients | Substances extracted from whole foods for cooking | Olive oil, honey, sea salt | Concentrated nutrients but used in small quantities |

| Processed Foods | Simple preservation techniques with few added ingredients | Canned tomatoes, cheese, smoked fish | Preserves nutrients with minor sodium/sugar additions |

| Ultra-Processed Foods | Industrial formulations with multiple additives | Soda, packaged snacks, ready-to-heat meals | Often high in sugar/salt, low in fiber and micronutrients |

Historical Timeline: How Food Processing Evolved

Food processing isn't a modern invention—it's a survival strategy humans have refined for millennia. Understanding this evolution helps contextualize today's food landscape:

- Prehistoric Era: Early humans discovered fire for cooking (improving digestibility and safety)

- 8000 BCE: Fermentation techniques developed for preserving dairy (yogurt, cheese) and vegetables (sauerkraut)

- 1809: Nicolas Appert invented canning to preserve food for Napoleon's army

- 1920s: Freezing technology became commercially viable, preserving nutrients better than canning

- 1950s: Post-war industrialization led to convenience foods and the rise of additives

- 2009: NOVA classification system introduced to categorize processing levels

According to FDA records, the shift toward ultra-processed foods accelerated after World War II when food scientists developed techniques to extend shelf life and enhance flavors for mass production.

When Processing Benefits Health (And When It Doesn't)

Not all processing is created equal. Context determines whether processing enhances or diminishes nutritional value:

Situations Where Processing Adds Value

- Nutrient preservation: Flash-freezing vegetables within hours of harvest locks in vitamins better than "fresh" produce shipped long distances

- Food safety: Pasteurization eliminates harmful bacteria in dairy and juices

- Accessibility: Canned beans and tomatoes provide affordable nutrition year-round

- Fortification: Adding vitamin D to milk or folic acid to flour addresses public health deficiencies

Situations Where Processing Creates Problems

- Additive overload: Ultra-processed foods often contain emulsifiers, artificial colors, and preservatives linked to health issues in Harvard research

- Nutrient stripping: Refined grains lose 75% of B vitamins and iron during processing

- Hyper-palatable formulations: Engineered combinations of sugar, fat, and salt override natural satiety signals

- Displacement effect: Heavy reliance on processed options reduces intake of whole foods and fiber

Smart Shopping Strategies for Processed Foods

You don't need to eliminate all processed foods—just become a savvy navigator of the grocery aisles. Try these evidence-based approaches:

Read Between the Lines on Labels

Look beyond marketing claims like "natural" or "healthy" to examine the actual ingredient list:

- Choose products with 5 or fewer recognizable ingredients

- Watch for hidden sugars (appearing as high-fructose corn syrup, maltose, or dextrose)

- Compare sodium levels—aim for less than 140mg per serving

- Seek whole grains as the first ingredient (not enriched flour)

Apply the "Would My Great-Grandmother Recognize This?" Test

As food writer Michael Pollan suggests, if your great-grandmother wouldn't identify an ingredient, consider limiting that product. This simple heuristic helps avoid many ultra-processed items without requiring nutrition expertise.

Balance Your Plate Strategy

Follow the USDA's MyPlate guidelines adapted for processed foods:

- 50% of your plate: Minimally processed fruits and vegetables

- 25%: Whole grains or minimally processed starches

- 25%: Protein sources (prioritize unprocessed over processed options)

- Use processed items as condiments or occasional additions, not meal foundations

What the Research Really Says About Health Impacts

Recent studies reveal nuanced relationships between processing levels and health outcomes. A 2019 JAMA Internal Medicine study tracking 40,000 adults found that a 10% increase in ultra-processed food consumption correlated with a 12% higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

However, not all processing carries equal risk. The same study showed that minimally processed frozen vegetables or canned beans didn't demonstrate negative health associations. The key differentiator appears to be the degree of industrial formulation and additive content.

Nutrition scientists now emphasize that we should focus less on "processed" as a blanket term and more on how foods are processed and what has been added or removed during processing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is bread considered a processed food?

Yes, most bread is processed, but the level varies significantly. Artisan bread with just flour, water, yeast, and salt represents minimal processing. Commercial bread often contains dough conditioners, preservatives, and added sugars, making it more heavily processed. Whole-grain breads with short ingredient lists offer the best nutritional profile among processed bread options.

Are frozen vegetables healthy despite being processed?

Yes, frozen vegetables are typically flash-frozen at peak ripeness, preserving nutrients better than fresh produce that travels long distances. They undergo minimal processing with no additives. Studies show frozen produce often has comparable or higher nutrient levels than "fresh" supermarket produce harvested before peak ripeness.

What's the difference between processed and ultra-processed foods?

Processed foods typically have 2-5 ingredients and use traditional preservation methods (canning, freezing, fermenting). Examples include canned beans, cheese, and smoked fish. Ultra-processed foods contain 5+ ingredients including industrial additives, artificial flavors, and colors. They're formulated for hyper-palatability and long shelf life (soda, packaged snacks, ready-to-heat meals). The NOVA classification system distinguishes these categories based on processing purpose and extent.

Can processed foods be part of a healthy diet?

Absolutely. Many minimally processed foods enhance nutrition and convenience. Frozen vegetables, canned tomatoes, plain yogurt, and roasted nuts all undergo processing that preserves nutrients or improves safety without compromising health benefits. The key is prioritizing foods with recognizable ingredients and limiting ultra-processed options high in added sugars, sodium, and artificial additives.

How can I identify ultra-processed foods quickly?

Look for these red flags: ingredient lists longer than 5 items, unrecognizable ingredients (like maltodextrin or xanthan gum), added sugars in multiple forms (high-fructose corn syrup, cane juice, dextrose), and claims like "artificially flavored" or "contains preservatives." Products requiring little preparation (ready-to-eat meals, packaged snacks) are often ultra-processed. When in doubt, compare similar products and choose the one with the shortest, most recognizable ingredient list.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4