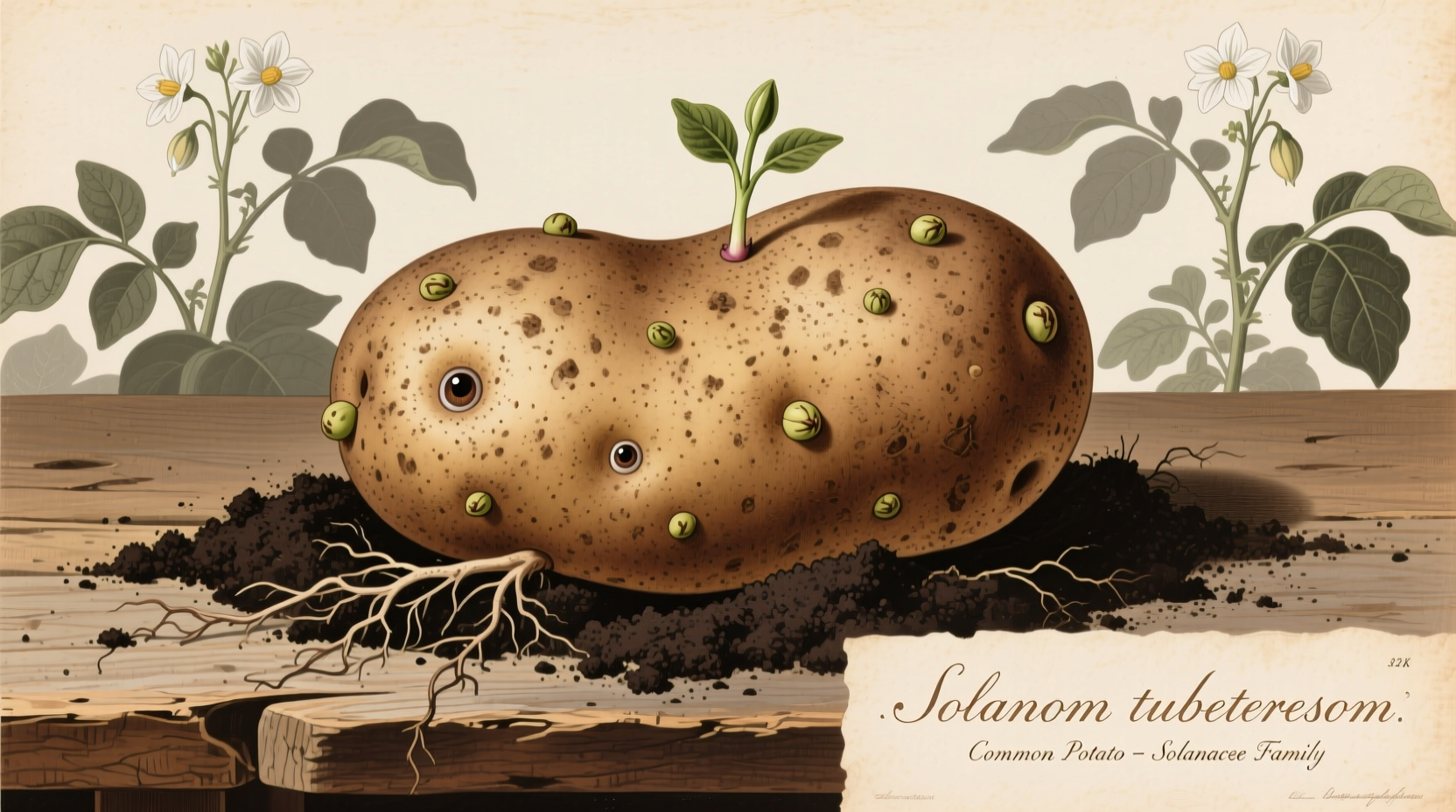

A potato is a starchy tuberous crop from the nightshade family Solanaceae, scientifically classified as Solanum tuberosum. Contrary to common belief, potatoes are not root vegetables but modified underground stems called tubers that store nutrients for the plant. Originating in the Andes mountains of South America over 7,000 years ago, potatoes now rank as the world's fourth-largest food crop after maize, wheat, and rice.

Ever wondered why this humble vegetable appears in cuisines worldwide yet gets misunderstood so often? You're not alone. Whether you're a home cook selecting the perfect spud for your recipe, a student researching plant biology, or simply curious about this dietary staple, understanding what a potato truly is transforms how you use and appreciate it. This guide cuts through common misconceptions to deliver scientifically accurate information you can trust.

The Botanical Reality: What Makes a Potato a Potato

Despite frequent classification errors, potatoes belong to the Solanaceae family alongside tomatoes and eggplants, not with root vegetables like carrots or beets. The edible portion develops as an underground stem modification called a stolon, which swells to form tubers. These tubers contain "eyes" - actually axillary buds capable of sprouting new plants. This biological distinction matters because it affects how potatoes grow, store, and behave in cooking.

According to the USDA Agricultural Research Service, over 5,000 potato varieties exist worldwide, each with unique characteristics suited to specific climates and culinary applications. The common misconception that potatoes are roots persists because they grow underground, but their stem-based origin explains why they contain more starch and less sugar than true root vegetables.

From Andean Highlands to Global Staple: A Historical Timeline

Potatoes began their journey in modern-day southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia, where indigenous peoples first domesticated them between 8,000 and 5,000 BCE. Spanish conquistadors introduced potatoes to Europe in the late 16th century, though widespread adoption took nearly two centuries due to initial suspicion about this nightshade family member.

| Time Period | Key Development | Global Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 8,000-5,000 BCE | Domestication in Andes mountains | Foundation of Inca civilization's food system |

| 1536 | Spanish introduction to Europe | Initial resistance due to nightshade family association |

| 1719 | Introduction to North America | Gradual adoption as reliable crop in cooler climates |

| 1795 | Antoine-Augustin Parmentier's promotion in France | Breaking European resistance through royal endorsement |

| 1845-1852 | Potato blight causes Irish famine | Global awareness of potato's agricultural importance |

| Present day | Global production exceeds 380 million tons annually | Fourth largest food crop worldwide after maize, wheat, and rice |

Understanding Potato Varieties: Matching Type to Purpose

Not all potatoes perform equally in every dish. Their starch content and moisture levels determine their best culinary applications. Generally categorized as waxy, starchy, or all-purpose, each type serves specific cooking functions:

- Starchy potatoes (Russet, Idaho): High starch, low moisture - ideal for baking, mashing, and frying

- Waxy potatoes (Red Bliss, Fingerling): Low starch, high moisture - maintain shape for salads and roasting

- All-purpose potatoes (Yukon Gold, Kennebec): Balanced starch content - versatile for most cooking methods

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension confirms that starch content directly affects texture outcomes. Russets contain 20-22% starch, making them fluffy when cooked, while waxy varieties contain only 16-18% starch, yielding firmer results. This scientific understanding helps home cooks achieve perfect results consistently.

Nutritional Profile: More Than Just Carbohydrates

Often unfairly maligned as "empty carbs," potatoes actually deliver significant nutritional value when prepared properly. A medium-sized potato with skin provides:

- 45% of the daily value for vitamin C

- More potassium than a banana

- Substantial vitamin B6 and dietary fiber

- Natural plant compounds with antioxidant properties

Research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health indicates that how you prepare potatoes dramatically affects their nutritional impact. Baking or boiling with skin intact preserves nutrients, while frying significantly increases calorie density. The glycemic index varies by preparation method and potato type - boiled new potatoes rate lower than mashed russets.

Practical Considerations: When Potatoes Aren't the Best Choice

While incredibly versatile, potatoes have specific limitations worth noting. For individuals managing diabetes, the high glycemic load of certain preparations requires careful portion control. Those following nightshade-free diets for autoimmune conditions must avoid potatoes entirely due to naturally occurring glycoalkaloids.

Proper storage proves crucial for maintaining quality and safety. The National Potato Council recommends keeping potatoes in a cool, dark place between 45-50°F (7-10°C) - never in the refrigerator, which converts starch to sugar. Exposure to light causes greening and increased solanine production, a natural toxin that can cause digestive upset in sensitive individuals.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4