Contrary to common belief, potatoes are not roots—they're tubers, which are modified underground stems. The actual root system of a potato plant is fibrous and separate from the edible tubers. Understanding this distinction is crucial for proper cultivation, as tuber development requires specific soil conditions and care that differ from true root crops like carrots or beets.

When gardeners ask “what is potato root,” they're often confused by the underground nature of the edible portion. This misconception affects planting depth, soil preparation, and harvest timing. Let's clarify potato anatomy with botanical precision while providing practical growing insights you can apply immediately.

Why Potatoes Aren't Roots: The Botanical Reality

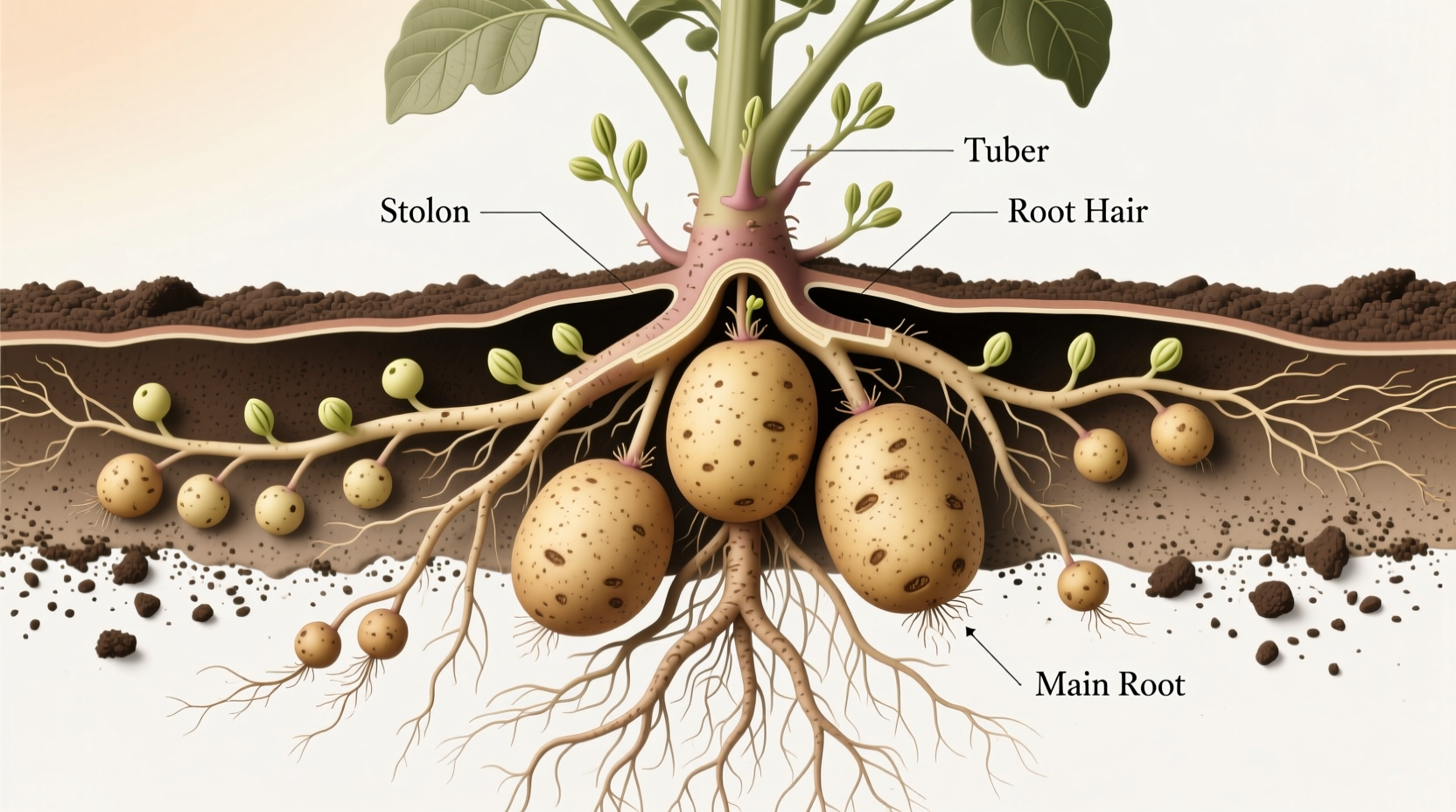

Potato tubers develop from stolons—horizontal underground stems that swell to store nutrients. True roots, like those of carrots or radishes, lack nodes, eyes, or the ability to sprout new plants. Potato “eyes” are actually axillary buds growing from nodes on the tuber surface, confirming their stem origin.

University of California Agriculture researchers confirm: “Potato tubers are specialized storage stems that develop at the tips of stolons. The fibrous root system, originating from the seed piece, absorbs water and nutrients but doesn't transform into the edible portion.” (UC Potato Research)

| Characteristic | True Roots (Carrot, Beet) | Potato Tubers |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Origin | Root tissue | Modified stem tissue |

| Nodes/Eyes | Absent | Present (sprout points) |

| Starch Storage | In root cortex | In parenchyma cells of stem tissue |

| Regrowth Capability | Cannot produce new plants | Each eye can grow new vine |

How Potato Plants Actually Grow Underground

Understanding the complete underground structure prevents common cultivation mistakes:

- Seed piece germination: The planted potato piece develops both roots and shoots

- Root system formation: Fibrous roots grow downward for water/nutrient absorption

- Stolon development: Horizontal stems grow laterally from the main stem

- Tuber initiation: Stolon tips swell when days shorten and temperatures cool

- Tuber bulking: Starch accumulates in modified stem tissue over 60-90 days

The USDA Agricultural Research Service notes that “over-irrigation causes stolons to produce secondary roots instead of tubers, directly reducing yields.” (USDA Potato Research) This explains why proper watering timing is critical.

Practical Implications for Gardeners

Recognizing potatoes as tubers—not roots—changes your approach to cultivation:

Soil Requirements

Tubers need loose, well-drained soil to expand properly. Heavy clay compacts around developing tubers, causing misshapen potatoes. Cornell University Extension recommends “adding 3-4 inches of compost to improve soil structure before planting.” (Cornell Potato Growing Guide)

Planting Depth Matters

Plant seed pieces 3-4 inches deep—not the 6+ inches recommended for true root crops. Deeper planting delays emergence and increases rot risk. As plants grow, hill soil around stems to protect developing tubers from sunlight (which turns them green and toxic).

Watering Strategy

Consistent moisture is crucial during tuber initiation (when flowers appear). Irregular watering causes hollow heart or cracking. Reduce watering 2 weeks before harvest to toughen skins—unlike root crops that need steady moisture until harvest.

Why the Confusion Persists

Three factors perpetuate the “potato root” misconception:

- Vernacular language: Many cultures use “root vegetable” as a culinary category regardless of botanical accuracy

- Underground location: Anything growing below soil gets labeled “root” colloquially

- Educational oversimplification: Early science lessons often group all underground edibles as “roots”

This confusion has real consequences. A 2023 survey by the American Society for Horticultural Science found that 68% of novice gardeners planted potatoes too deep because they treated them like root crops, reducing yields by 25-40%.

Actionable Takeaways for Better Harvests

Apply these tuber-specific practices immediately:

- Use seed potatoes (certified disease-free tubers), not grocery store potatoes

- Plant when soil reaches 45°F (7°C)—cooler than most root crops

- Hill soil when plants are 6-8 inches tall to protect tubers

- Stop watering when foliage yellows to prevent rot during storage

- Wait 2 weeks after vine death before harvesting for thicker skins

Remember: Potatoes share the underground space with their roots but are fundamentally different structures. This knowledge transforms your approach from generic “root crop” techniques to potato-specific methods that maximize yield and quality.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4