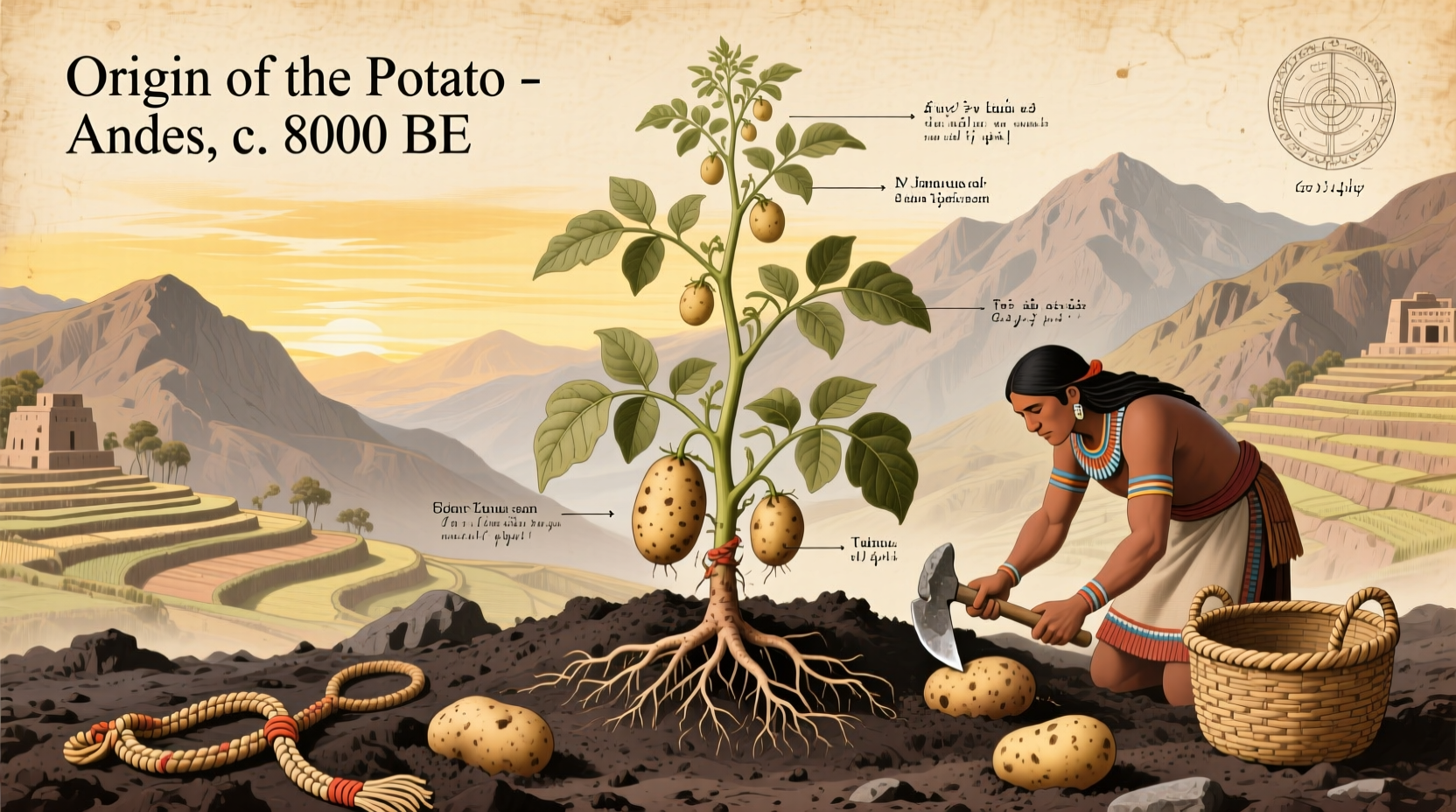

From Andean Highlands to Global Staple: The Potato's Remarkable Journey

For centuries, the humble potato has sustained civilizations, transformed economies, and shaped culinary traditions worldwide. But few realize this dietary cornerstone began as a wild tuber in the harsh conditions of the Andes Mountains. Understanding potato origins history reveals not just botanical evolution, but how one crop reshaped human civilization.

The Andean Birthplace: Where It All Began

Archaeological evidence confirms potato cultivation began between 8,000-10,000 years ago in the region surrounding Lake Titicaca, straddling modern Peru and Bolivia. Indigenous communities selectively bred wild Solanum species, developing thousands of potato varieties adapted to different elevations and microclimates. The Inca civilization elevated potato cultivation to an art form, developing freeze-drying techniques to create chuño—a lightweight, non-perishable food source that sustained their vast empire.

Unlike today's uniform supermarket varieties, ancient Andean farmers cultivated astonishing diversity. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru documents over 4,000 native potato varieties still grown in the Andes, each with unique colors, textures, and culinary properties. This genetic diversity proved crucial for the potato's global adaptation.

Timeline of Potato History: Key Milestones

| Time Period | Development | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 8,000-10,000 BCE | Initial domestication in Andes | Wild tubers selectively bred into edible varieties |

| 2,500 BCE | Widespread cultivation across Andes | Development of freeze-drying techniques for preservation |

| 1536 CE | Spanish conquistadors encounter potatoes | First European documentation of potatoes |

| 1570-1590s | Potatoes introduced to Europe | Initial resistance due to nightshade family association |

| 1700s | Adoption as staple crop across Europe | Population growth linked to reliable potato yields |

| 1845-1852 | Irish Potato Famine | Phytophthora infestans devastates monoculture crops |

| Present Day | Global production exceeds 400 million tons annually | Fourth most important food crop worldwide after maize, wheat, rice |

The Spanish Connection: Global Dispersal Begins

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America in the 16th century, they discovered potatoes sustaining the Inca Empire. Historical records from Spanish chroniclers like Pedro Cieza de León (1553) document indigenous potato cultivation techniques. Initially skeptical of this unfamiliar nightshade family member, Europeans gradually recognized the potato's nutritional value and adaptability.

By the late 16th century, potatoes reached Spain and began spreading across Europe. Historical resistance was significant—many considered potatoes poisonous due to their relation to deadly nightshade. It took influential advocates like Antoine-Augustin Parmentier in France (who convinced Louis XVI to promote potato cultivation) to overcome cultural resistance. The potato's ability to grow in poor soils with minimal care eventually won over European farmers, dramatically increasing food security.

Botanical Classification and Genetic Journey

Scientifically classified as Solanum tuberosum, potatoes belong to the nightshade family (Solanaceae), which includes tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants. Modern genetic research confirms all cultivated potatoes descend from a single domestication event in the Andes. The USDA Agricultural Research Service notes that wild potato species still grow across the Americas from the southwestern United States to southern Chile.

The journey from Andean staple to global crop required significant adaptation. European varieties developed thicker skins to withstand transportation, while tuber shapes changed to suit different culinary traditions. The International Potato Center's research shows that just 178 native Andean varieties formed the genetic foundation for all modern commercial potatoes—a concerning lack of diversity that makes global crops vulnerable to disease.

Cultural Impact: How Potatoes Transformed Societies

The introduction of potatoes triggered profound demographic shifts. Historical analysis published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics demonstrates that potato cultivation contributed to approximately 12% of the population growth in the Old World between 1700-1900. Regions adopting potatoes experienced reduced famine mortality and increased caloric intake, particularly benefiting lower socioeconomic classes.

However, this dependence created vulnerability. The Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852) tragically demonstrated the risks of monoculture when Phytophthora infestans (potato blight) devastated Ireland's primary food source, causing approximately one million deaths and triggering mass emigration. This historical event underscores why preserving the genetic diversity found in the Andes remains critical for future food security.

Modern Understanding of Potato Origins History

Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of potato origins. Paleobotanical studies analyzing starch residues on ancient Andean pottery confirm potato use dating to 3,000 BCE. Genetic sequencing projects like those at the Sainsbury Laboratory in the UK are mapping the complete potato genome to identify disease-resistant traits from wild relatives.

Today, the Andes remains the center of potato diversity, with communities in Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador maintaining traditional cultivation practices. Organizations like the International Potato Center (CIP) work with indigenous farmers to preserve heirloom varieties while developing climate-resilient strains for global agriculture. This ongoing research highlights why understanding potato origins history isn't just academic—it's vital for addressing modern food security challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where did potatoes originally come from?

Potatoes originated in the Andes Mountains of South America, specifically in the region around Lake Titicaca spanning modern-day Peru and Bolivia. Archaeological evidence shows domestication began 8,000-10,000 years ago by indigenous communities who selectively bred wild potato species.

How did potatoes spread from South America to the rest of the world?

Spanish conquistadors encountered potatoes in the 1530s and brought them to Europe in the late 16th century. Initial resistance gave way to widespread adoption as farmers recognized their nutritional value and ability to grow in poor soils. By the 18th century, potatoes had become a staple crop across Europe and began spreading to other continents through colonial trade routes.

Why were potatoes initially rejected in Europe?

Europeans initially distrusted potatoes because they belonged to the nightshade family, which includes poisonous plants like belladonna. Many considered them unfit for human consumption, associating them with witchcraft or believing they caused leprosy. It took influential advocates like Antoine-Augustin Parmentier in France to overcome these misconceptions through public demonstrations and royal endorsements.

How many varieties of potatoes existed historically compared to today?

Indigenous Andean farmers developed over 4,000 native potato varieties adapted to different elevations and conditions. In contrast, modern commercial agriculture relies on fewer than 200 varieties globally, with most supermarkets carrying just a dozen types. This dramatic reduction in genetic diversity makes global potato crops more vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

What role did potatoes play in historical population growth?

Research published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics shows potato cultivation contributed to approximately 12% of the population growth in the Old World between 1700-1900. Potatoes provided more calories per acre than grain crops, reduced infant mortality, and allowed populations to thrive in marginal agricultural regions, particularly benefiting lower socioeconomic classes with access to reliable nutrition.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4