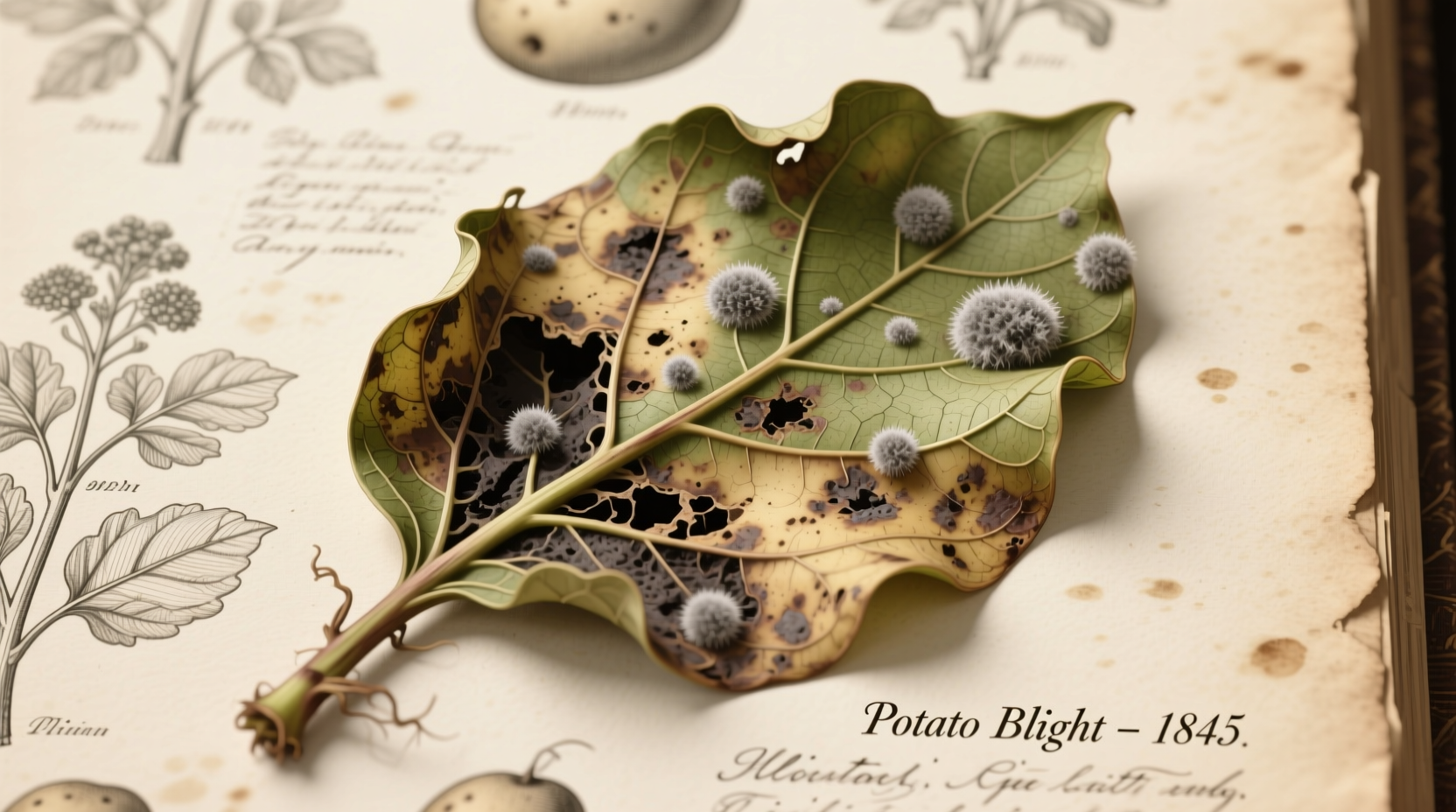

Irish potato blight, caused by the water mold Phytophthora infestans, rapidly destroys potato foliage and tubers in cool, wet conditions. This devastating plant disease triggered the Great Irish Famine (1845-1852), killing approximately one million people and forcing another million to emigrate. Today, it remains a serious threat to potato crops worldwide, requiring vigilant monitoring and management practices.

For gardeners and farmers, understanding this destructive pathogen isn't just historical curiosity—it's essential crop protection knowledge. When left unchecked, potato blight can wipe out an entire harvest in days during favorable weather conditions. The good news? Modern prevention strategies and resistant varieties have dramatically reduced its impact compared to the 19th century.

From Historical Tragedy to Modern Agricultural Challenge

The story of Irish potato blight begins long before it reached Europe. Researchers believe Phytophthora infestans originated in central Mexico's Toluca Valley, where wild potato relatives co-evolved with the pathogen. The disease likely traveled to Europe aboard merchant ships in the 1840s, finding ideal conditions in Ireland's cool, damp climate and spreading rapidly through the island's potato-dependent agricultural system.

| Key Historical Timeline of Irish Potato Blight | Events and Impact |

|---|---|

| 1843-1844 | First reported outbreaks in eastern United States |

| June 1845 | Disease detected in Belgium, then rapidly spreads across Europe |

| September 1845 | First confirmed cases in Ireland near Dublin |

| 1845-1849 | Great Famine period—potato crops fail repeatedly |

| 1847 | "Black '47"—worst famine year with approximately 400,000 deaths |

| 1852 | Famine officially ends, but population decline continues for decades |

Understanding the Science Behind Potato Blight

Despite its name, potato blight isn't caused by a fungus but by Phytophthora infestans, a water mold (oomycete) more closely related to algae than fungi. This distinction matters because many fungicides don't effectively control oomycetes.

The pathogen spreads through airborne spores that thrive in temperatures between 45-70°F (7-21°C) with high humidity or leaf wetness. Under ideal conditions, the disease cycle can complete in just 5-7 days, explaining its terrifying speed during the Irish Famine.

How to Identify Potato Blight in Your Garden

Early detection is critical for managing potato blight. Look for these telltale signs:

- Initial symptoms: Dark, water-soaked lesions on leaf edges that rapidly expand

- Progression: Lesions turn brown with a light green halo; white fungal growth appears on leaf undersides in humid conditions

- Advanced infection: Entire plants collapse; tubers develop reddish-brown rot beneath the skin

- Distinctive feature: Infected tissue often has a distinctive musty odor

Don't confuse potato blight with other common potato diseases. Unlike early blight (which creates target-like concentric rings) or bacterial soft rot (which causes mushy decay), potato blight spreads rapidly across entire fields during cool, wet weather.

Effective Prevention and Management Strategies

While we can't change the weather, modern growers have powerful tools to combat potato blight:

Cultural Practices That Reduce Risk

- Variety selection: Plant resistant varieties like 'Sarpo Mira', 'Defender', or 'Elba'

- Proper spacing: Allow 3-4 feet between plants for better air circulation

- Irrigation management: Water early in the day so foliage dries quickly; avoid overhead watering

- Crop rotation: Rotate potatoes with non-host crops (like grains) for at least 3 years

- Sanitation: Remove and destroy infected plant material; don't compost diseased plants

When Fungicides Become Necessary

For serious outbreaks, organic gardeners can use copper-based sprays as a preventive measure, applied before symptoms appear. Commercial growers often use more targeted systemic fungicides, but resistance management requires rotating different chemical classes.

According to the USDA Agricultural Research Service, integrated management approaches combining resistant varieties with strategic fungicide applications reduce blight incidence by 70-90% compared to untreated fields. Their research shows that monitoring weather conditions using the USAblight risk model helps growers apply treatments only when necessary, reducing chemical use by 30%.

Is Potato Blight Still a Threat Today?

Absolutely. While modern agriculture has reduced its impact, potato blight remains a serious global concern. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that Phytophthora infestans still causes $6.7 billion in annual crop losses worldwide.

Recent outbreaks demonstrate its ongoing threat:

- 2009: Severe outbreak in the northeastern United States destroyed up to 75% of crops in some areas

- 2010: Unusually cool, wet summer in Europe led to widespread blight problems

- 2022: Climate change patterns have expanded blight's potential range into previously unaffected regions

Researchers at Cornell University's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences note that new, more aggressive strains of the pathogen have emerged since the 1980s, overcoming some previously resistant varieties. Their ongoing work focuses on developing durable resistance through both traditional breeding and genetic approaches.

Protecting Your Potato Harvest: Action Plan

Follow this practical timeline for effective blight management:

- Before planting: Select resistant varieties and prepare well-drained soil

- Early season: Monitor weather using blight forecasting tools like USAblight

- When conditions favor blight: Apply preventive treatments (copper for organic, appropriate fungicides for conventional)

- At first sign of disease: Immediately remove infected leaves (if caught early) or entire plants (if widespread)

- During harvest: Carefully inspect tubers; store only perfect specimens in cool, dry conditions

- After harvest: Practice strict crop rotation and sanitation

Remember that complete eradication is impossible—our goal is effective management. By understanding the disease cycle and implementing integrated strategies, you can significantly reduce losses and enjoy a successful potato harvest even in blight-prone regions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4