Understanding potato carbohydrate content helps you make informed dietary choices whether you're managing blood sugar, tracking macros, or simply eating mindfully. This guide delivers precise nutritional data from authoritative sources, practical preparation insights, and context for incorporating potatoes into various eating patterns.

Breaking Down Potato Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates in potatoes primarily consist of starch, with smaller amounts of fiber and natural sugars. The exact composition varies significantly based on potato variety, size, and preparation method. Unlike processed carbs, potato carbohydrates come packaged with essential vitamins, minerals, and fiber that affect how your body processes them.

Starch makes up about 70-80% of potato carbohydrates, providing sustained energy release when consumed with the skin. The resistant starch content increases when potatoes are cooled after cooking, offering additional digestive benefits. This natural carbohydrate profile differs substantially from refined grains and processed foods that lack accompanying nutrients.

Potato Varieties Compared: Carb Content Analysis

Different potato types deliver varying carbohydrate profiles. The USDA's comprehensive nutrient database provides standardized measurements that account for typical preparation methods and edible portions.

| Potato Type | Size | Total Carbs | Dietary Fiber | Sugars | Net Carbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

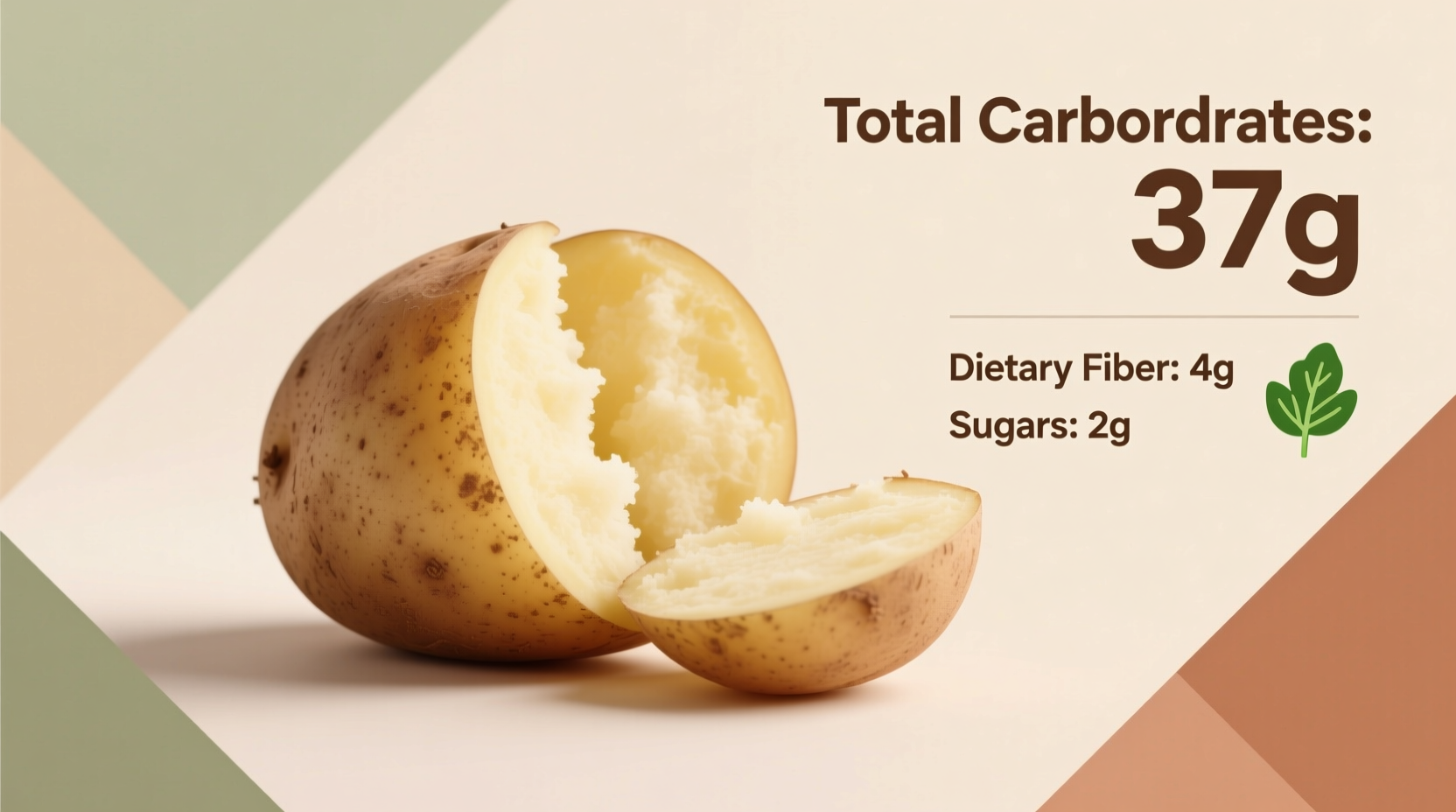

| Russet | Medium (173g) | 37g | 4.6g | 2.3g | 32.4g |

| Sweet Potato | Medium (130g) | 27g | 3.8g | 5.1g | 23.2g |

| Red Potato | Medium (150g) | 32g | 3.4g | 1.7g | 28.6g |

| Yukon Gold | Medium (150g) | 30g | 3.0g | 1.5g | 27g |

Data source: USDA FoodData Central, accessed September 2025. Measurements reflect edible portion after standard preparation.

How Cooking Methods Transform Carb Content

Your preparation technique significantly impacts the final carbohydrate profile of potatoes. While total carb content remains relatively stable by weight, cooking alters starch structure and digestibility:

- Boiling: Causes minimal carb change but increases resistant starch when cooled (up to 15% more than hot)

- Baking: Concentrates carbs slightly through moisture loss (about 10% higher density than boiled)

- Frying: Adds negligible carbs from oil but creates acrylamide compounds at high temperatures

- Microwaving: Preserves most nutrients with minimal structural change to starches

Notably, cooling cooked potatoes increases resistant starch content by 20-30%, which functions more like fiber in your digestive system. This transformation occurs through retrogradation, where starch molecules reorganize into a form that resists digestion. The effect peaks after 24 hours of refrigeration, making potato salad potentially more gut-friendly than hot mashed potatoes.

Nutritional Context: Potatoes in Your Daily Diet

For perspective, the 37 grams of carbs in a medium russet potato represents approximately 13% of the recommended daily carbohydrate intake for a 2,000-calorie diet. However, the glycemic impact varies considerably based on what you eat with your potatoes:

- Eating potatoes with protein sources like chicken or fish slows glucose absorption

- Adding healthy fats such as olive oil reduces the glycemic response by 30-40%

- Consuming potatoes with vinegar lowers post-meal blood sugar spikes by up to 35%

- Serving potatoes alongside non-starchy vegetables creates a more balanced meal

Research published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition demonstrates that whole potatoes consumed with their skin have a lower glycemic index than processed potato products. The fiber content in potato skin (nearly half the total fiber) plays a crucial role in moderating blood sugar response.

Practical Guidance for Different Dietary Needs

Whether you're following a specific eating pattern or managing health conditions, these evidence-based strategies help you enjoy potatoes appropriately:

For Blood Sugar Management

Pair potatoes with acidic components like lemon juice or vinegar, which can reduce the glycemic response by slowing gastric emptying. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends consuming potatoes as part of mixed meals rather than as standalone carbohydrate sources for better glucose control.

For Weight Management

Research from the University of California shows that cooled potatoes increase satiety hormones by 25% compared to hot preparations. The resistant starch formed during cooling acts as a prebiotic, supporting gut bacteria associated with healthy weight regulation.

For Athletic Performance

Sports nutritionists often recommend potatoes as an excellent carb source before endurance events. A study in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition found boiled potatoes provided comparable performance benefits to commercial carbohydrate gels during prolonged exercise, with added nutritional advantages.

Common Misconceptions About Potato Carbs

Several persistent myths cloud potato nutrition understanding. Scientific evidence reveals:

- Myth: All potato carbs are "bad" for blood sugar

Fact: Whole potatoes with skin have a moderate glycemic index (54-62), lower than white bread (70-85) - Myth: Sweet potatoes are always lower in carbs than regular potatoes

Fact: Per 100g, sweet potatoes contain slightly fewer carbs but more sugar than russets - Myth: Potato carbs cause weight gain

Fact: Population studies show no association between whole potato consumption and obesity when prepared without added fats

The USDA Agricultural Research Service emphasizes that preparation method and portion size matter more than the potato itself when considering carbohydrate impact.

Putting Potato Carbs in Historical Context

Understanding how we've measured potato nutrition reveals important insights about modern data:

- 1940s-1970s: Early nutrition science focused primarily on caloric content with limited carb differentiation

- 1980s: Glycemic index research began distinguishing between rapidly and slowly digested carbs

- 1990s: Resistant starch concept emerged, changing how we view cooked and cooled potato nutrition

- 2000s-Present: Advanced analytical methods allow precise breakdown of carb types and their metabolic effects

This evolution explains why older sources sometimes present conflicting information about potato carbohydrates. Modern analytical techniques provide more nuanced understanding of how different potato preparations affect your body.

Smart Potato Selection and Preparation

Maximize nutritional benefits while managing carb intake with these practical tips:

- Choose smaller portions (4-6 oz) of whole potatoes rather than large servings

- Always eat potatoes with their skin for maximum fiber content

- Cool cooked potatoes before eating to increase resistant starch

- Pair potatoes with protein and healthy fats to moderate blood sugar response

- Experiment with vinegar-based dressings to enhance satiety

- Consider purple potatoes for higher antioxidant content with similar carb profiles

Registered dietitians increasingly recognize potatoes as nutrient-dense carbohydrate sources when prepared appropriately. The key lies in understanding portion sizes and preparation methods that optimize their nutritional profile for your individual needs.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4