The potato originated in the Andes mountains of South America approximately 8,000-5,000 BCE, was introduced to Europe in the late 16th century, and has since become the world's fourth-largest food crop. This comprehensive history explores how a humble tuber transformed global agriculture, fueled population growth, caused devastating famines, and became a culinary staple across cultures.

For centuries, the potato has quietly shaped human civilization in ways few other foods have. From its ancient origins in the Andes to its status as a global staple, this unassuming tuber has influenced economies, altered population patterns, and even changed the course of history. Understanding the potato's journey reveals how a single crop can transform societies and why this history remains relevant to our food security today.

From Andean Highlands to Global Staple: The Potato's Remarkable Journey

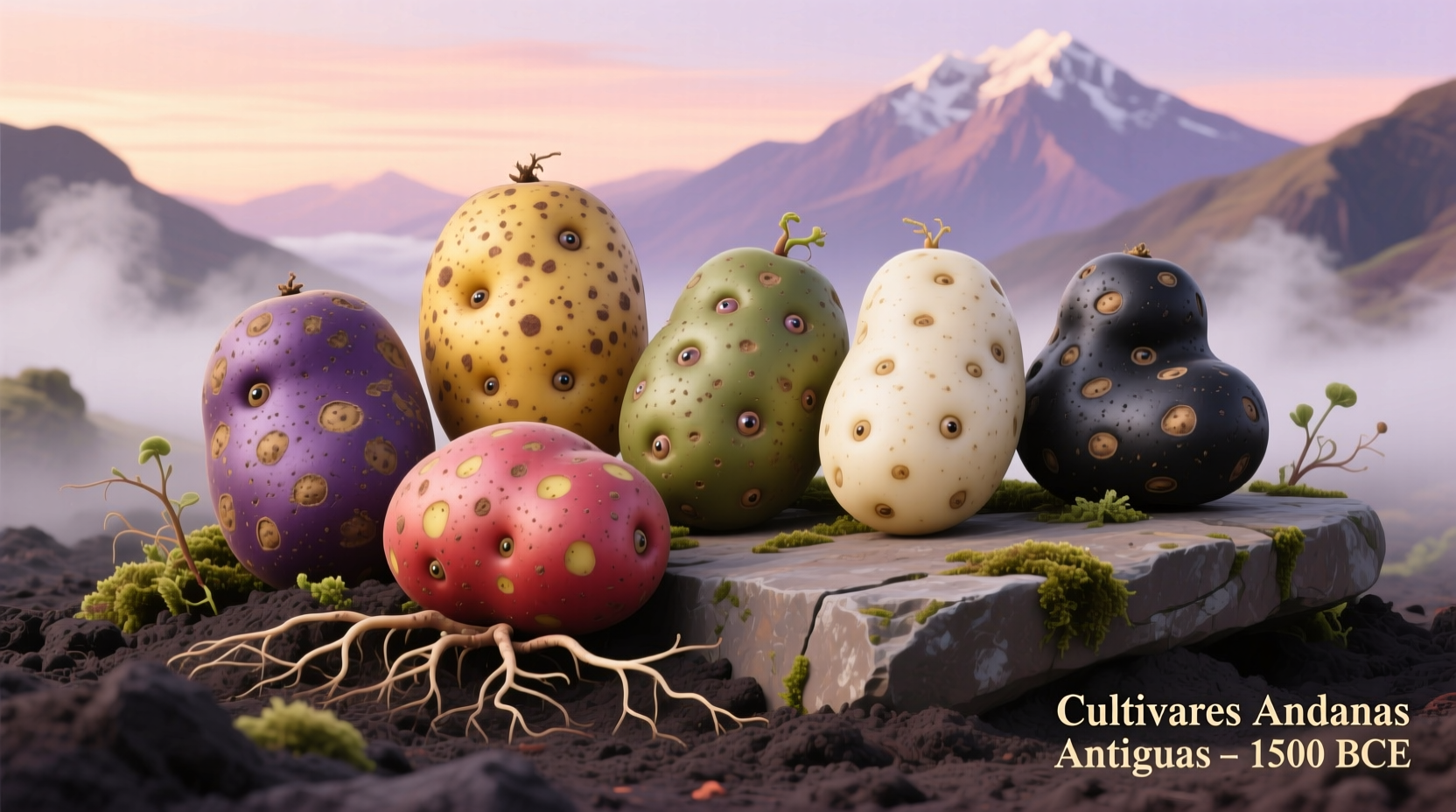

Long before Europeans set foot in the Americas, indigenous peoples in the Andes mountains had already mastered the cultivation of over 3,000 potato varieties. Archaeological evidence from sites near Lake Titicaca confirms potato domestication between 8,000 and 5,000 BCE, making it one of humanity's earliest cultivated crops. The Inca civilization revered the potato not just as food but as a sacred element of their culture, developing sophisticated agricultural techniques like freeze-drying to create chuño, a preservation method still used today.

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 16th century, they encountered this versatile crop that could thrive at high altitudes where other staples failed. Spanish historian Pedro Cieza de León documented potatoes in 1553, noting their importance to Andean communities. The first potatoes reached Spain around 1570, though historical records show confusion between potatoes and sweet potatoes, which had arrived earlier via different routes.

The Global Spread: Resistance, Adoption, and Transformation

Europe's initial reception of the potato was anything but enthusiastic. Many Europeans distrusted this unfamiliar tuber, believing it caused leprosy or was unfit for human consumption. French pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier championed the potato in the 18th century after discovering its nutritional value while imprisoned during the Seven Years' War. His clever marketing campaign, including royal endorsements and guarded potato fields designed to spark curiosity, helped overcome public resistance.

By the 1770s, the potato had become a crucial crop across Europe. Its ability to produce more calories per acre than grain crops made it instrumental in supporting population growth during the Industrial Revolution. In Ireland, where the potato required less land than grain crops, it became the primary food source for the rural poor, with a single acre potentially feeding an entire family.

| Historical Period | Key Developments | Global Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 8,000-5,000 BCE | Domestication in Andes mountains | Foundation for Andean civilizations |

| 1530s-1570s | Introduction to Europe via Spanish explorers | Initial resistance followed by gradual adoption |

| 1700s | Widespread cultivation across Europe | Population growth, reduced famine vulnerability |

| 1845-1852 | Irish Potato Famine | 1 million deaths, 1 million emigrations, global diaspora |

| 20th-21st century | Global expansion, scientific breeding | World's fourth-largest food crop, diverse culinary applications |

The Irish Potato Famine: A Turning Point in History

The devastating Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1852 represents one of the most significant events in potato history. When Phytophthora infestans, a water mold causing late blight, arrived in Europe, Ireland's dependence on the 'Lumper' potato variety—grown for its high yield but lacking genetic diversity—proved catastrophic. Within weeks, entire crops rotted in the fields.

The consequences were profound: approximately one million people died from starvation and related diseases, while another million emigrated, primarily to North America. This mass migration reshaped demographics across the Atlantic, influencing politics, culture, and labor markets for generations. The famine also spurred advances in plant pathology and highlighted the dangers of monoculture farming—a lesson still relevant to modern agricultural practices.

Modern Potato Production and Cultural Significance

Today, the potato stands as the world's fourth-largest food crop after maize, wheat, and rice, with global production exceeding 380 million tons annually according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). China leads global production, followed by India, Ukraine, and Russia. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports over 200 potato varieties cultivated commercially worldwide, though thousands of heirloom varieties exist, particularly in the Andean region.

Culinary traditions across the globe have embraced the potato in distinctive ways:

- Peru: Causa, Papa a la Huancaína, and over 3,000 traditional varieties

- Ireland: Colcannon, boxty, and champ

- France: Pommes dauphine, pommes frites, and gratin dauphinois

- India: Aloo gobi, samosas, and dum aloo

- United States: Mashed potatoes, french fries, and potato salad

Scientific advancements continue to shape potato history. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru, maintains the world's largest collection of potato diversity, preserving over 7,000 accessions. Researchers are developing climate-resilient varieties and exploring the potato's potential beyond food, including industrial applications and nutritional fortification to address vitamin deficiencies in developing countries.

Why Potato History Matters Today

Understanding the potato's historical journey offers valuable insights for contemporary challenges. The Irish Potato Famine serves as a stark reminder of the importance of crop diversity for food security. With climate change threatening agricultural stability, the potato's adaptability—growing in diverse conditions from the Andes to Scandinavian fields—makes it increasingly important.

Modern consumers can appreciate how this historical perspective enhances everyday cooking. Knowing that different potato varieties evolved for specific purposes—waxy for boiling, starchy for mashing—helps home cooks select the right type for each recipe. The resurgence of heirloom varieties connects us to centuries of agricultural knowledge while supporting biodiversity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where did potatoes originally come from?

Potatoes were first domesticated in the Andes mountains of South America between 8,000 and 5,000 BCE. Archaeological evidence from sites near Lake Titicaca confirms this early cultivation, where indigenous peoples developed sophisticated agricultural techniques for growing and preserving potatoes at high altitudes.

How did potatoes spread from South America to the rest of the world?

Spanish explorers introduced potatoes to Europe in the late 16th century, with the first documented arrival in Spain around 1570. Initially met with suspicion, potatoes gradually gained acceptance through the efforts of advocates like French pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier in the 18th century. From Europe, potatoes spread to other continents through trade and colonization.

What caused the Irish Potato Famine?

The Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852) was caused by Phytophthora infestans, a water mold that causes late blight. Ireland's heavy reliance on the 'Lumper' potato variety, which lacked genetic diversity, made the crop extremely vulnerable. When the blight arrived, it rapidly destroyed the primary food source for Ireland's rural poor, leading to approximately one million deaths and one million emigrations.

How many varieties of potatoes exist worldwide?

There are over 5,000 varieties of potatoes worldwide, with the greatest diversity found in the Andean region of South America. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru maintains a collection of over 7,000 potato accessions. Commercially, however, only about 200 varieties are widely cultivated, with popular types including Russet Burbank, Yukon Gold, and Maris Piper.

Why are potatoes important for global food security today?

Potatoes rank as the world's fourth-largest food crop and provide more calories per acre than most cereal grains. Their adaptability to diverse growing conditions, relatively short growing season, and high nutritional value make them crucial for food security. Organizations like the International Potato Center are developing climate-resilient varieties to address challenges posed by climate change while preserving genetic diversity essential for future food security.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4