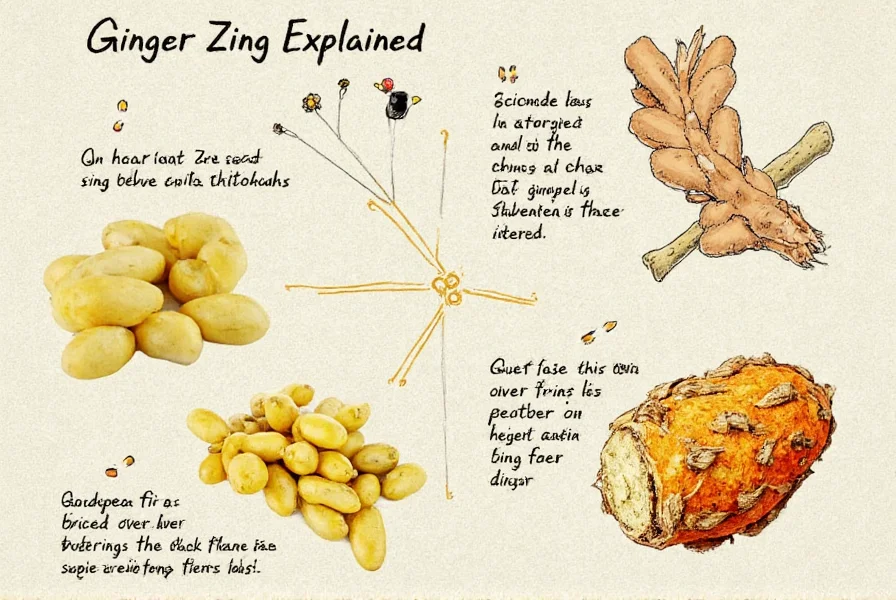

Ginger’s characteristic bite isn’t just a flavor sensation—it’s a biochemical interaction between your taste receptors and specific compounds evolved as the plant’s natural defense mechanism. Understanding these compounds unlocks better culinary applications and maximizes potential health benefits. This comprehensive guide explores the science behind ginger’s zing, how preparation methods affect its potency, and practical ways to harness its properties.

The Chemistry of Ginger’s Signature Zing

Gingerol, specifically 6-gingerol, constitutes approximately 60% of fresh ginger’s pungent compounds. This phenolic compound activates TRPV1 receptors—the same receptors triggered by capsaicin in chili peppers—creating that familiar warming sensation. Unlike capsaicin’s sharp burn, gingerol produces a more complex flavor profile with citrusy, peppery notes that dissipate faster.

When ginger undergoes different processing methods, its chemical composition transforms significantly:

| Preparation Method | Primary Compound | Pungency Level | Flavor Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh ginger | Gingerol | Moderate | Sharp, citrusy, clean heat |

| Dried ginger | Shogaols | High | Intense, woody, lingering heat |

| Cooked ginger | Zingerone | Low-Moderate | Sweet, warm, mellow spice |

| Fermented ginger | Paradols | Moderate-High | Complex, rounded heat with earthy notes |

How Processing Methods Transform Ginger’s Zing

The transformation between these compounds occurs through specific chemical processes. Dehydration converts gingerol to shogaols, which are approximately twice as pungent. This explains why dried ginger powder delivers a more intense kick than fresh root. When ginger is cooked, particularly in acidic environments like vinegar or citrus, gingerol converts to zingerone, creating a mellower, sweeter spice profile ideal for baked goods and warm beverages.

Chefs and home cooks can strategically manipulate these transformations. For maximum zing in stir-fries, add fresh ginger late in the cooking process. For deeper, warmer notes in curries, sauté ginger early to develop zingerone. When making ginger tea, crushing fresh ginger releases more gingerol, while simmering converts it to the gentler zingerone.

Health Implications of Ginger’s Active Compounds

Research indicates these compounds contribute to ginger’s well-documented health benefits. Gingerol demonstrates potent anti-inflammatory properties, with studies showing it inhibits COX-2 enzymes similar to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but without the gastrointestinal side effects. Shogaols, while more pungent, show enhanced antioxidant capacity and may offer greater neuroprotective benefits according to recent phytochemical research.

The varying bioavailability of these compounds affects their therapeutic potential. Fresh ginger’s gingerol has lower bioavailability but provides immediate sensory effects, while shogaols from dried ginger demonstrate higher absorption rates. For digestive support, fresh ginger’s rapid action makes it ideal for nausea relief, whereas dried ginger may provide longer-lasting anti-inflammatory effects.

Maximizing Ginger Zing in Culinary Applications

Understanding these chemical transformations allows precise control over ginger’s flavor impact. For beverages requiring pronounced zing, use freshly grated ginger with minimal heating. The enzyme myrosinase, active in raw ginger, enhances pungency when combined with acidic ingredients like lemon juice. In contrast, for subtle background warmth in baked goods, cooked or dried ginger works better.

Professional chefs employ several techniques to modulate ginger’s intensity:

- Freezing ginger before grating increases cell rupture, releasing more gingerol

- Combining ginger with fats (like coconut milk) helps distribute pungent compounds evenly

- Adding ginger to cold preparations (like dressings) preserves volatile compounds

- Peeling ginger reduces fiber content without significantly affecting pungency

Storage Methods That Preserve Ginger’s Potency

Proper storage significantly impacts ginger’s zing retention. Whole, unpeeled ginger root maintains maximum potency for 2-3 weeks when stored in a paper bag in the refrigerator’s crisper drawer. Freezing whole ginger preserves gingerol content for up to six months, with minimal degradation of pungent compounds. Avoid storing ginger in water or airtight containers, which accelerates enzymatic breakdown of gingerol.

Dried ginger powder loses potency more rapidly than fresh root. Store in an airtight container away from light and heat to preserve shogaol content for 6-12 months. The moment you open a container of ginger powder, volatile compounds begin evaporating, so purchase smaller quantities more frequently for maximum zing.

Safety Considerations and Optimal Consumption

While generally safe, excessive ginger consumption can cause heartburn or interact with blood-thinning medications due to gingerol’s antiplatelet effects. The European Medicines Agency recommends no more than 4 grams of ginger daily for adults. Those with gallstones should consult physicians before consuming large amounts, as ginger stimulates bile production.

Individual tolerance varies significantly. Start with small amounts (1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon grated fresh ginger) and gradually increase to determine personal tolerance. The pungency that makes ginger valuable therapeutically can become overwhelming if not properly balanced with other flavors in culinary applications.

Practical Applications for Home and Professional Kitchens

Understanding ginger’s chemistry transforms how you incorporate it into recipes. For immediate flavor impact in salads or cold soups, use freshly grated ginger with citrus juice to preserve gingerol. When making ginger simple syrup for cocktails, simmering converts gingerol to zingerone for a smoother, less aggressive spice. In fermented preparations like kimchi, ginger’s compounds interact with lactic acid bacteria to create unique flavor compounds not found in either ingredient alone.

Professional mixologists leverage these transformations to create balanced ginger cocktails. Muddled fresh ginger provides upfront zing in Moscow Mules, while ginger-infused syrups offer more integrated warmth in spirit-forward drinks. The key is matching the ginger preparation method to the desired sensory experience—whether you want an immediate spicy kick or subtle background warmth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4