Understanding the true meaning behind \"eye of newt\" requires examining historical herbology practices and Shakespearean context. During the medieval and Renaissance periods, apothecaries and herbalists often used cryptic names for common plants and ingredients. This served multiple purposes: protecting trade secrets, making remedies seem more potent, and aligning with mystical traditions.

The Shakespeare Connection

William Shakespeare immortalized the phrase in Macbeth (Act IV, Scene I) with the witches' chant: \"Eye of newt and toe of frog, Wool of bat and tongue of dog...\" For centuries, readers interpreted these ingredients literally, creating a persistent misconception. However, historical research into Elizabethan herbology reveals these were coded terms for ordinary plants.

Why Mustard Seed Was Called \"Eye of Newt\"

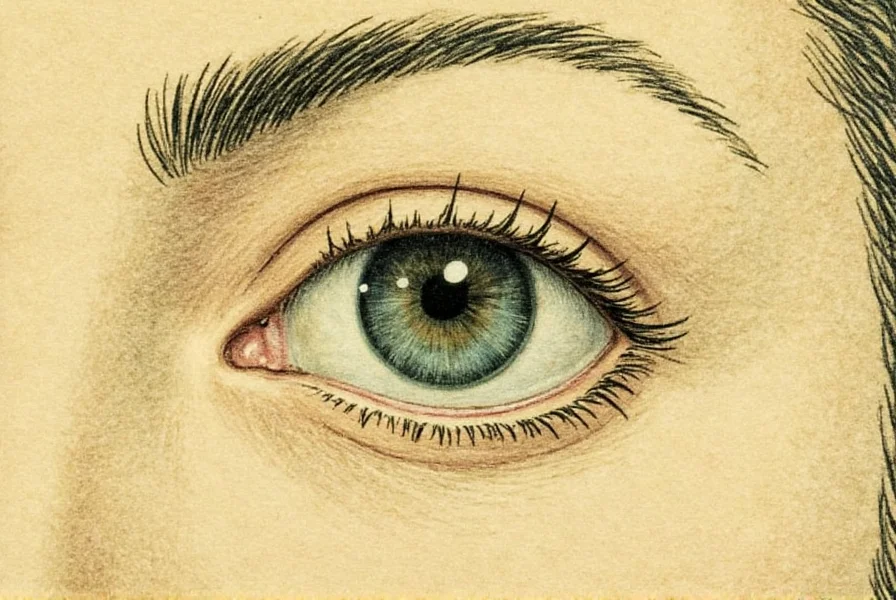

The connection between \"eye of newt\" and mustard seed stems from visual similarity and linguistic evolution:

| Historical Term | Actual Plant | Reason for Naming |

|---|---|---|

| Eye of newt | Mustard seed | Small, round seeds resemble a newt's eye |

| Toe of frog | Buttercup | Foot-like flower shape |

| Wool of bat | Hemp | Fibrous texture resembling bat fur |

Mustard seeds (Brassica nigra) are small, round, and dark—similar in appearance to a newt's eye. The term \"newt\" itself wasn't even used until after Shakespeare's time; the creature was called an \"eft\" in the 16th century. This linguistic evolution further complicated the misunderstanding.

Medieval Herbology Naming Practices

Herbalists like Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) documented these naming conventions in works such as The Complete Herbal. Plants received imaginative names based on:

- Appearance: Physical resemblance to animals or body parts

- Doctrine of Signatures: Belief that plants resembling body parts could treat those areas

- Trade protection: Obscuring ingredients to maintain competitive advantage

- Mystical associations: Connecting plants to supernatural properties

This practice explains why \"eye of newt mustard seed\" appears in historical texts—it was standard terminology, not a reference to actual animal parts. Modern scholars like Marjorie Nichols have traced these connections through herbology manuscripts from the 15th-17th centuries.

Modern Misconceptions and Clarifications

The confusion persists because:

- Shakespeare's dramatic context suggested literal ingredients

- Later adaptations portrayed witches using actual animal parts

- Few readers consult historical herbology references

- The term \"newt\" entered common usage after Shakespeare's time

When researching \"what does eye of newt mean\" or \"eye of newt in Macbeth meaning\", it's crucial to consult historical botanical sources rather than theatrical interpretations. The phrase represents how language evolves and how cultural context shapes our understanding of historical texts.

Practical Implications Today

Understanding the \"eye of newt mustard seed\" connection matters for:

- Literary analysis: Accurate interpretation of Shakespeare and other historical texts

- Historical cooking: Recreating authentic medieval recipes

- Botanical studies: Tracing the evolution of plant nomenclature

- Cultural literacy: Recognizing how language shapes perception

For those exploring \"historical meaning of eye of newt\" or researching \"medieval herbology terms\", this knowledge provides crucial context. Modern herbalists sometimes use the original terms for authenticity when recreating historical remedies, though they substitute actual mustard seed for the archaic phrase.

Does \"eye of newt\" literally mean an eye from a newt?

No, \"eye of newt\" never referred to an actual newt's eye. Historical evidence confirms it was the medieval term for mustard seed, based on the seed's visual similarity to a newt's eye. This was part of a common practice where herbalists used mysterious names for ordinary plants.

Why did Shakespeare use \"eye of newt\" in Macbeth?

Shakespeare used \"eye of newt\" because it was standard terminology in contemporary herbology texts. The phrase would have been immediately recognizable to Elizabethan audiences as mustard seed. He incorporated these ingredients to create an authentic witches' brew that reflected common beliefs about magical potions during that era.

What other ingredients in the witches' brew were misnamed?

Several ingredients in Macbeth's witches' brew used coded terms: \"Toe of frog\" meant buttercup, \"wool of bat\" referred to hemp, and \"tongue of dog\" was houndstongue plant. These were all standard herbology terms that described common plants through metaphorical naming conventions popular in medieval and Renaissance medicine.

Can I use \"eye of newt\" in cooking today?

Yes, but you'll need to substitute mustard seed. When recreating historical recipes that call for \"eye of newt\", modern cooks use black mustard seeds. The term \"eye of newt\" has no culinary meaning today beyond this historical reference, so always use actual mustard seed if attempting period-accurate cooking.

How did medieval people name plants and ingredients?

Medieval herbalists used descriptive, often metaphorical names based on appearance (\"eye of newt\" for mustard seed), perceived medicinal properties (\"lungwort\" for lung conditions), or mystical associations. This practice, called the Doctrine of Signatures, helped practitioners remember plant uses but created confusion that persists in historical texts like Shakespeare's works.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4