Ever stood in the grocery store wondering why some sweet potatoes are labeled as yams? You're not alone. This confusion affects millions of shoppers who want to make informed choices about these nutritious tubers. Understanding the real difference between yams and sweet potatoes helps you select the right ingredient for your recipes, maximize nutritional benefits, and avoid common shopping mistakes.

Botanical Reality: Two Completely Different Plants

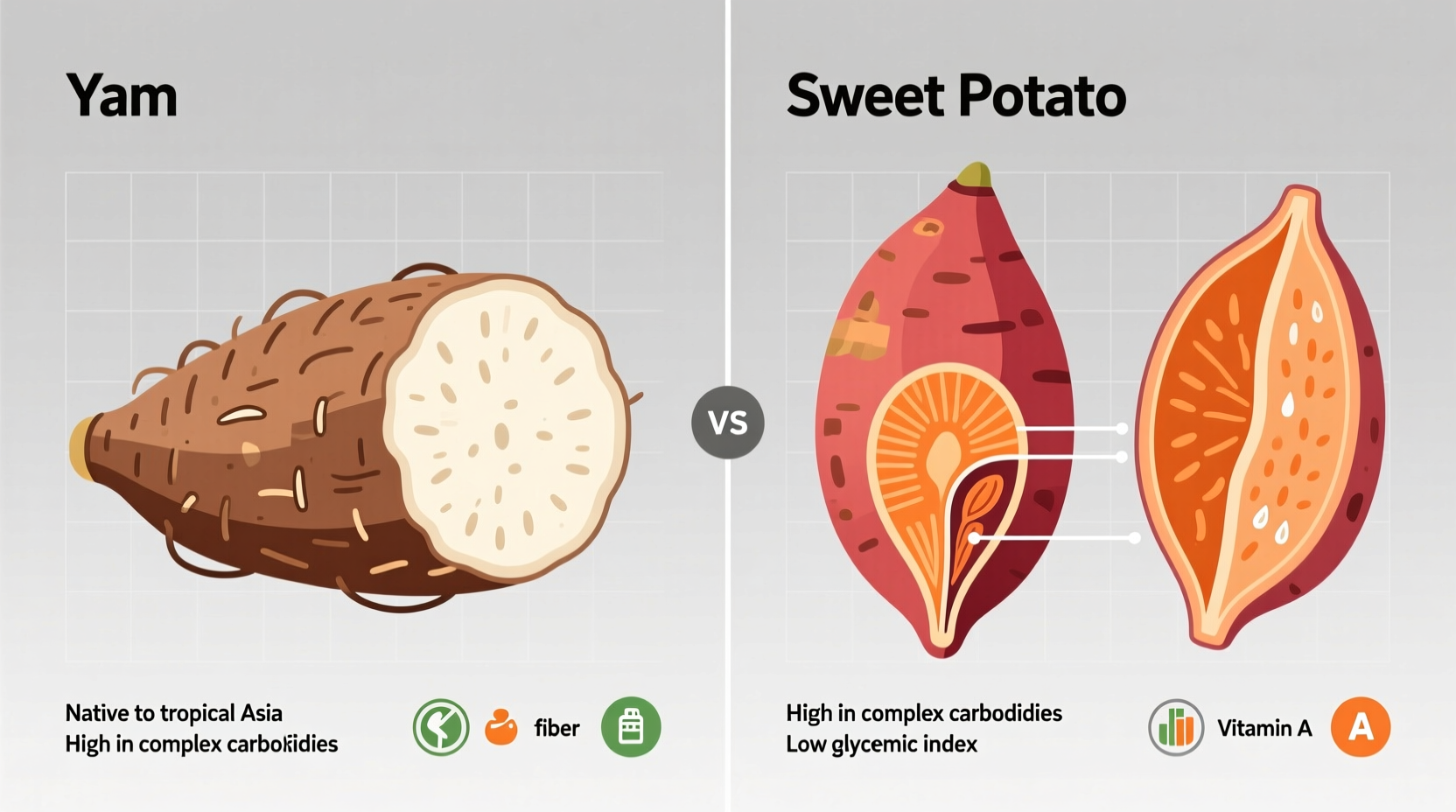

Despite common labeling practices, yams and sweet potatoes belong to entirely separate plant families. Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) are part of the morning glory family (Convolvulaceae), while true yams (Dioscorea species) belong to the Dioscoreaceae family. This fundamental botanical distinction explains their different growing requirements, nutritional profiles, and culinary properties.

| Characteristic | True Yam | Sweet Potato |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Family | Dioscoreaceae | Convolvulaceae |

| Scientific Name | Dioscorea spp. | Ipomoea batatas |

| Origin | Africa, Asia | Central/South America |

| Skin Texture | Rough, bark-like, scaly | Smooth, thin, sometimes reddish |

| Flesh Color | White, purple, or reddish | Orange, white, purple |

| Starch Content | Very high (up to 80% starch) | Moderate (around 20% starch) |

| Sweetness | Low (starchy, neutral flavor) | High (naturally sweet) |

Why the Confusion? A Historical Timeline

The mislabeling of sweet potatoes as yams in the United States dates back to the early 20th century. Here's how this persistent confusion developed:

- Pre-1930s: African slaves brought knowledge of true yams (Dioscorea species) from West Africa to America, but couldn't find them in the New World

- 1930s: Louisiana sweet potato growers began marketing their moist, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes as “yams” to distinguish them from drier, white-fleshed varieties

- 1950s: The U.S. Department of Agriculture mandated that any sweet potato labeled as “yam” must also include “sweet potato” on the label

- Present Day: Grocery stores continue using “yam” for orange sweet potatoes despite USDA requirements, perpetuating the confusion

According to research from the USDA Agricultural Research Service, this historical mislabeling has created such widespread confusion that most Americans believe yams and sweet potatoes are the same vegetable or different varieties of the same plant.

Nutritional Comparison: What You're Really Eating

Understanding the nutritional differences matters for both health and cooking. The USDA FoodData Central database shows significant nutritional variations between true yams and sweet potatoes:

- Vitamin A: Orange sweet potatoes contain over 400% of the daily value per serving, while true yams contain negligible amounts

- Vitamin C: Sweet potatoes provide about 30% of daily needs per serving; yams offer only 15%

- Potassium: Both are excellent sources, but sweet potatoes contain approximately 20% more per serving

- Glycemic Index: Sweet potatoes generally have a lower glycemic index (44-94 depending on cooking method) compared to yams (70-90)

Research published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition confirms that orange-fleshed sweet potatoes are among the most vitamin A-dense foods available, making them particularly valuable in regions where vitamin A deficiency is common.

Where to Find True Yams vs. Sweet Potatoes

Knowing where to find each tuber prevents shopping mistakes. In the United States:

- True yams: Available primarily in African, Caribbean, and Asian specialty markets, not mainstream grocery stores

- Sweet potatoes labeled as “yams”: Found in all major supermarkets (these are actually just orange-fleshed sweet potatoes)

- White-fleshed sweet potatoes: Often labeled correctly as “sweet potatoes” or “hard sweet potatoes”

The International Potato Center, a research institution focused on root and tuber crops, notes that true yams require specific tropical growing conditions and represent less than 1% of the tuber market in North America. What you're buying as “yams” in standard US grocery chains are always sweet potatoes.

Culinary Applications: Choosing the Right Tuber

Understanding the differences helps you select the best option for your recipes:

- For baking and desserts: Orange-fleshed “soft” sweet potatoes (often mislabeled as yams) work best due to their natural sweetness

- For savory dishes needing neutral starch: True yams are ideal for African and Asian stews where a potato-like texture is needed

- For roasting: White-fleshed “hard” sweet potatoes maintain better structure than orange varieties

- For mashing: Orange sweet potatoes create naturally sweeter, creamier mash than true yams

Common Misconceptions Clarified

Several persistent myths continue to confuse shoppers:

- Myth: Yams are just a darker variety of sweet potato

- Fact: They're completely different plant species with distinct genetic lineages

- Myth: All orange tubers are yams

- Fact: Orange color indicates beta-carotene-rich sweet potatoes, not yams

- Myth: Yams and sweet potatoes can be used interchangeably in recipes

- Fact: Their different starch and sugar contents significantly affect cooking results

Food historians at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History confirm that the mislabeling practice was primarily a marketing strategy that became entrenched in American food culture, despite efforts by agricultural authorities to correct it.

Shopping Guide: What to Look for at the Store

When selecting tubers at your local market:

- For true yams: Look for very rough, almost bark-like skin, cylindrical shape, and white or purple flesh (typically found in ethnic markets)

- For orange sweet potatoes (“soft” type): Smooth reddish skin, deep orange flesh, often labeled as “yams”

- For white sweet potatoes (“hard” type): Light tan skin, pale yellow or white flesh, labeled as “sweet potatoes”

Remember that the USDA requires that any product labeled as “yam” must also include “sweet potato” on the packaging, though this regulation is frequently ignored in practice.

Global Perspectives on Naming

The confusion isn't universal. In many countries, the distinction remains clear:

- Nigeria: “Ji” refers to true yams, while sweet potatoes are called “George”

- Japan: True yams are “nagaimo” while sweet potatoes are “satsumaimo”

- Caribbean: True yams are distinguished from “boniato” (white sweet potatoes) and “batata” (orange sweet potatoes)

Anthropological research from the University of California shows that indigenous communities in West Africa, where true yams originated, maintain precise terminology distinguishing dozens of yam varieties based on texture, flavor, and agricultural properties.

Practical Takeaways for Home Cooks

Now that you understand the real differences, here's how to apply this knowledge:

- Don't worry about finding true yams for most American recipes—what's labeled as “yams” will work perfectly

- Choose orange-fleshed sweet potatoes for maximum vitamin A benefits

- Store sweet potatoes in a cool, dark place (not the refrigerator) for optimal shelf life

- When following international recipes, check whether they call for true yams or sweet potatoes

- Experiment with different sweet potato varieties to find your preferred texture and sweetness

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4