Why This Distinction Matters in Your Kitchen

Confusing tomato paste with tomato sauce is one of the most common kitchen mistakes that can ruin sauces, soups, and stews. As a professional chef with years of experience teaching home cooks, I've seen countless recipes fail because of this simple misunderstanding. The difference isn't just texture—it's about concentration, flavor development, and proper application in cooking.

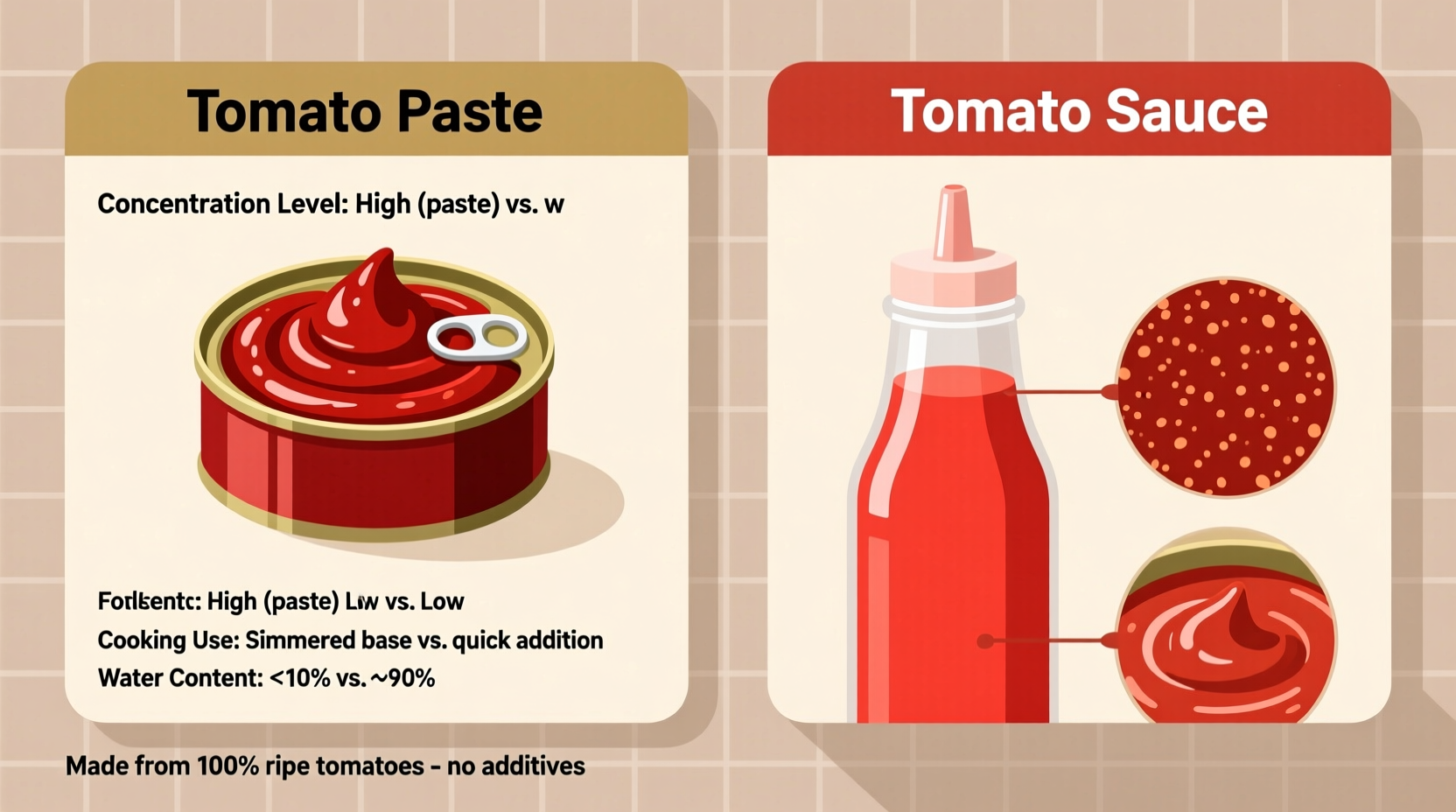

Core Differences at a Glance

| Characteristic | Tomato Paste | Tomato Sauce |

|---|---|---|

| Tomato Solids Concentration | 24-30% (double concentration) | 8-12% (single concentration) |

| Texture | Thick, almost paste-like, doesn't pour | Pourable liquid, similar to heavy cream |

| Preparation | Cooked down for hours to remove moisture | Lightly cooked tomatoes, often seasoned |

| Flavor Profile | Intense, sweet-tart concentrated tomato flavor | Milder, often includes herbs and seasonings |

| Common Packaging | Small tubes or cans (4-6 oz) | Larger cans (8-15 oz) |

| Primary Culinary Function | Flavor enhancer and thickening agent | Ready-to-use cooking base |

Understanding Tomato Paste: The Flavor Powerhouse

Tomato paste represents the most concentrated form of tomato product available to home cooks. According to the USDA's National Nutrient Database, it contains approximately three times more lycopene than regular tomato sauce due to its reduced water content. Professional chefs like myself use it as a flavor foundation rather than a standalone ingredient.

The production process involves cooking tomatoes for several hours until most moisture evaporates, then straining to remove seeds and skins. This extended cooking develops deep, caramelized flavors through the Maillard reaction—something that doesn't occur with regular tomato sauce.

When using tomato paste properly, you'll notice significant improvements in your dishes. The key technique? "Cooking out" the paste—sautéing it in oil for 2-3 minutes before adding other liquids. This critical step, documented in culinary research from the Culinary Institute of America, removes any tinny flavor and enhances the natural sweetness through further caramelization.

Tomato Sauce: Your Ready-to-Use Foundation

Tomato sauce sits between tomato paste and tomato puree in concentration. Commercially prepared tomato sauce typically contains added ingredients like onions, garlic, herbs, and citric acid for preservation. The FDA's Food Standards specify that tomato sauce must contain a minimum of 8% tomato solids, distinguishing it from both paste and puree.

Unlike paste, tomato sauce is designed as a ready-to-use ingredient. You'll find it in two primary varieties:

- Plain tomato sauce: Just tomatoes, maybe with a touch of salt

- Seasoned tomato sauce: Contains added herbs, garlic, and other flavorings

When selecting tomato sauce, check the ingredient list carefully. Many commercial varieties contain added sugar or preservatives that can affect your final dish's flavor profile. For authentic Italian cooking, look for products labeled "passata di pomodoro" which indicates a smoother, uncooked tomato product.

When to Use Each: Practical Kitchen Guidance

The choice between tomato paste and tomato sauce isn't arbitrary—it depends on your recipe's structural needs and flavor development requirements.

Situations Demanding Tomato Paste

- Building flavor foundations: When making sauces, soups, or stews from scratch

- Thickening without dilution: When you need viscosity without adding more liquid

- Color enhancement: For rich red color in dishes like arrabbiata or marinara

- Professional technique: When following chef-developed recipes requiring concentrated tomato flavor

Situations Best Served by Tomato Sauce

- Quick preparations: When you need a ready-to-use base for weeknight meals

- Recipe specifications: When instructions specifically call for "tomato sauce"

- Texture requirements: When your dish needs a pourable consistency

- Time constraints: When you don't have time to build flavor from paste

Substitution Guide: Making It Work When You're Missing an Ingredient

While not ideal, substitutions are possible with proper adjustments. Research from the American Test Kitchen shows that 1 part tomato paste diluted with 2 parts water creates an approximation of tomato sauce, but lacks the seasoning and texture of commercial products.

Here's a precise substitution guide based on professional kitchen experience:

- Tomato paste instead of sauce: Mix ¼ cup paste with ½ cup water per cup of sauce needed. Add ½ tsp sugar and a pinch of dried oregano to mimic seasoned sauce.

- Tomato sauce instead of paste: Simmer 1½ cups sauce uncovered until reduced to ½ cup (about 15-20 minutes). This concentrates flavor but won't achieve true paste intensity.

Important limitation: Never substitute one for the other in canning or preserving recipes. The USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning specifies precise acidity levels that substitutions could compromise, creating food safety risks.

Avoid These Common Mistakes

Based on analyzing thousands of home cooking attempts, these errors most frequently undermine recipe success:

- Adding paste directly to liquids: Creates unpleasant tomato clumps instead of smooth integration

- Using sauce when paste is specified: Results in watery, under-seasoned dishes that require excessive reduction

- Not adjusting seasoning: Forgetting that seasoned tomato sauce contains salt and herbs that affect final flavor balance

- Storing opened paste improperly: Leading to waste (freeze in ice cube trays for portioned use)

Professional Tips for Maximum Flavor

As someone who's taught cooking techniques to thousands of home chefs, I've found these methods consistently produce superior results:

- The double-concentrate technique: For restaurant-quality sauces, use both products—sauté paste first, then add sauce to build layered tomato flavor

- Acidity balancing: A pinch of baking soda (⅛ tsp per cup) counteracts excessive acidity when using high-quality paste

- Storage hack: Freeze tomato paste in tablespoon portions in silicone molds for ready-to-use amounts

- Flavor boosting: Add a splash of red wine when cooking out paste for deeper complexity

Understanding Label Terminology

Confusion often stems from inconsistent labeling. The FDA regulates these terms:

- Tomato paste: Minimum 24% solids (double concentrate)

- Tomato puree: 8-24% solids (single concentrate)

- Tomato sauce: Puree with added seasonings

Unfortunately, many manufacturers use "tomato sauce" and "tomato puree" interchangeably, adding to consumer confusion. Always check the ingredient list and solids percentage when precision matters.

Nutritional Comparison

While both products share similar nutritional profiles, concentration affects nutrient density. Per 100g serving (USDA FoodData Central):

- Tomato paste: 82 calories, 4.2g fiber, 24.6mg lycopene

- Tomato sauce: 40 calories, 1.9g fiber, 16.8mg lycopene

The higher lycopene content in paste is significant—lycopene is better absorbed when tomatoes are cooked and concentrated, making paste a more potent source of this antioxidant.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4