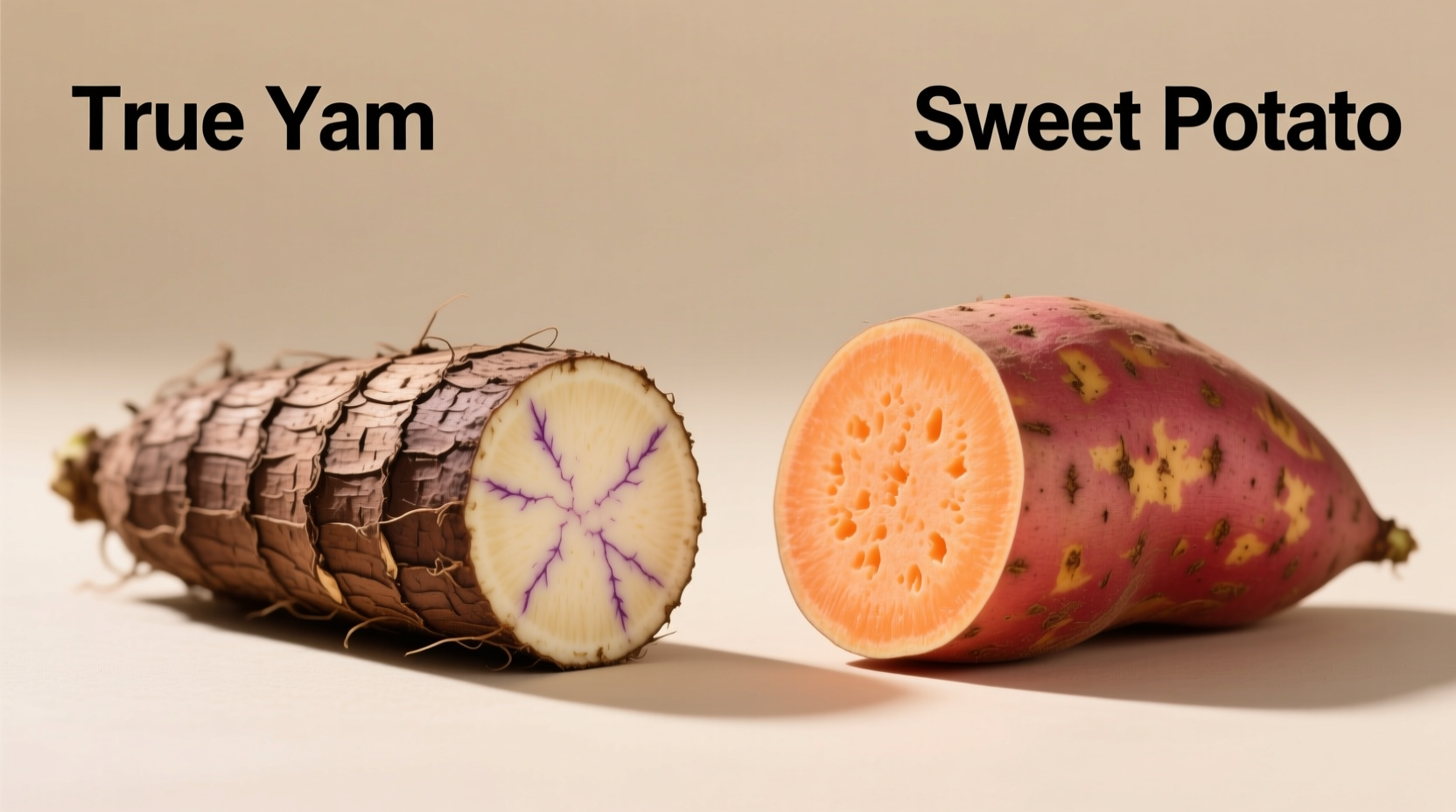

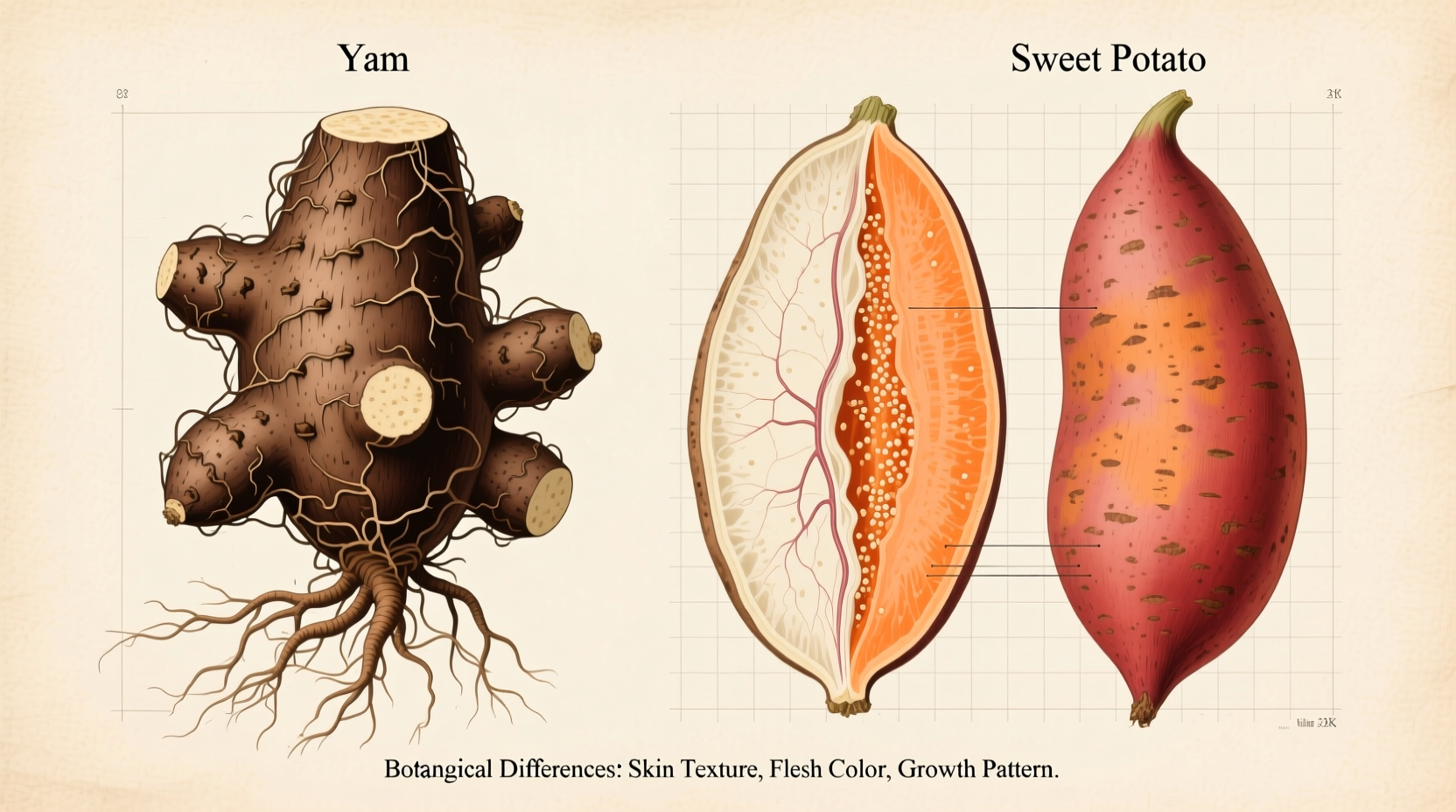

True yams and sweet potatoes are completely different plants. In the United States, what's labeled as “yams” are almost always just a variety of sweet potato with copper skin and orange flesh. Real yams have rough, bark-like skin, white or purple flesh, and are rarely found in standard American grocery stores.

Confused about yams vs sweet potatoes? You're not alone. For decades, American consumers have been mislabeled these two distinct root vegetables, creating widespread confusion that affects everything from holiday recipes to nutritional choices. Let's clear up this culinary mystery once and for all with scientifically accurate information you can trust.

The Great Grocery Store Mislabeling

Walk into any standard American supermarket and you'll likely see “yams” prominently displayed next to sweet potatoes. This labeling practice began in the 1930s when Louisiana growers needed to distinguish their moist, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes from the firmer, paler varieties already on the market. They borrowed the African word „nyami” (meaning “to eat”) and shortened it to “yam.” This marketing tactic stuck, creating decades of confusion.

| Characteristic | True Yam | Sweet Potato (Labeled as “Yam”) |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Family | Dioscoreaceae | Convolvulaceae |

| Origin | Africa, Asia, Caribbean | Central/South America |

| Skin Texture | Rough, bark-like, scaly | Thin, smooth, copper-colored |

| Flesh Color | White, purple, or reddish | Orange, yellow, or white |

| Starch Content | Very high (up to 35%) | Moderate (about 20%) |

| Sugar Content | Low | High (especially when cooked) |

How to Identify Them in Stores

When shopping, look beyond the labels. True yams (when available) have thick, rough skin resembling tree bark, often with black spots and root hairs. Their flesh is typically white, purple, or reddish. What's labeled as “yams” in most American stores are actually Jewel or Garnet sweet potato varieties with copper skin and orange flesh.

According to the USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service, all products labeled as “yams” in the United States must also include the term “sweet potato” to prevent consumer confusion, though this regulation is frequently ignored in practice.

Nutritional Differences That Matter

Understanding these differences is crucial for both culinary applications and nutritional planning. True yams contain significantly more starch and less sugar than sweet potatoes. A 100g serving of yam provides approximately 118 calories, 28g carbohydrates, and 0.5g sugar, while the same amount of sweet potato contains about 86 calories, 20g carbohydrates, and 4.2g sugar.

From a vitamin perspective, sweet potatoes dramatically outperform true yams in vitamin A content. One medium sweet potato provides over 400% of your daily vitamin A requirement, while yams contain negligible amounts. Both are good sources of vitamin C and potassium, but sweet potatoes contain nearly twice as much vitamin C as yams.

Culinary Applications: When to Use Which

The confusion extends to cooking applications. True yams maintain their structure better during cooking and have a more neutral flavor, making them ideal for West African dishes like fufu or Caribbean yam pies. Their high starch content creates a satisfying chewiness that holds up in stews.

Sweet potatoes (mislabeled as yams) caramelize beautifully when roasted, making them perfect for American-style candied yams, pies, and casseroles. Their natural sugars enhance baked goods, while their creamy texture works well in soups and purees.

Food scientists at Cornell University note that the Maillard reaction occurs differently in sweet potatoes versus true yams due to their varying sugar and amino acid profiles, explaining why sweet potatoes develop that characteristic caramelized flavor when roasted while true yams do not.

Global Context and Availability

Outside the United States, the distinction is much clearer. In Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean—where true yams are dietary staples—the term “yam” refers exclusively to Dioscorea species. Nigeria alone produces over 70% of the world's yam supply. In these regions, sweet potatoes are recognized as a separate crop with different preparation methods and cultural significance.

True yams require specific growing conditions—tropical climates with consistent rainfall—which explains their limited availability in temperate regions. They're typically planted at the beginning of the rainy season and harvested after 6-12 months, making them a more labor-intensive crop than sweet potatoes.

Shopping Guide: Getting What You Want

When shopping in the United States, ignore the “yam” labeling. Instead, look for these identifiers:

- For orange-fleshed sweet potatoes: Jewel, Garnet, or Beauregard varieties with copper skin

- For white-fleshed sweet potatoes: Hannah or O'Henry varieties with golden skin

- For true yams: Check specialty African or Caribbean markets; look for rough, bark-like skin and white or purple flesh

When purchasing sweet potatoes (often mislabeled as yams), choose firm roots without soft spots or cracks. Store them in a cool, dark place—not the refrigerator—where they'll keep for 3-5 weeks. True yams have a longer shelf life, often lasting 2-3 months when stored properly.

Common Misconceptions Clarified

Several persistent myths continue to confuse consumers:

- Myth: Yams are just a darker variety of sweet potato Fact: They belong to completely different plant families with distinct genetic profiles

- Myth: All orange-fleshed root vegetables are sweet potatoes Fact: Some true yam varieties do have orange flesh, though these are extremely rare in Western markets

- Myth: Yams and sweet potatoes can be used interchangeably in recipes Fact: Their different starch and sugar contents produce dramatically different results

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4