The Botanical Truth Behind Tomatoes

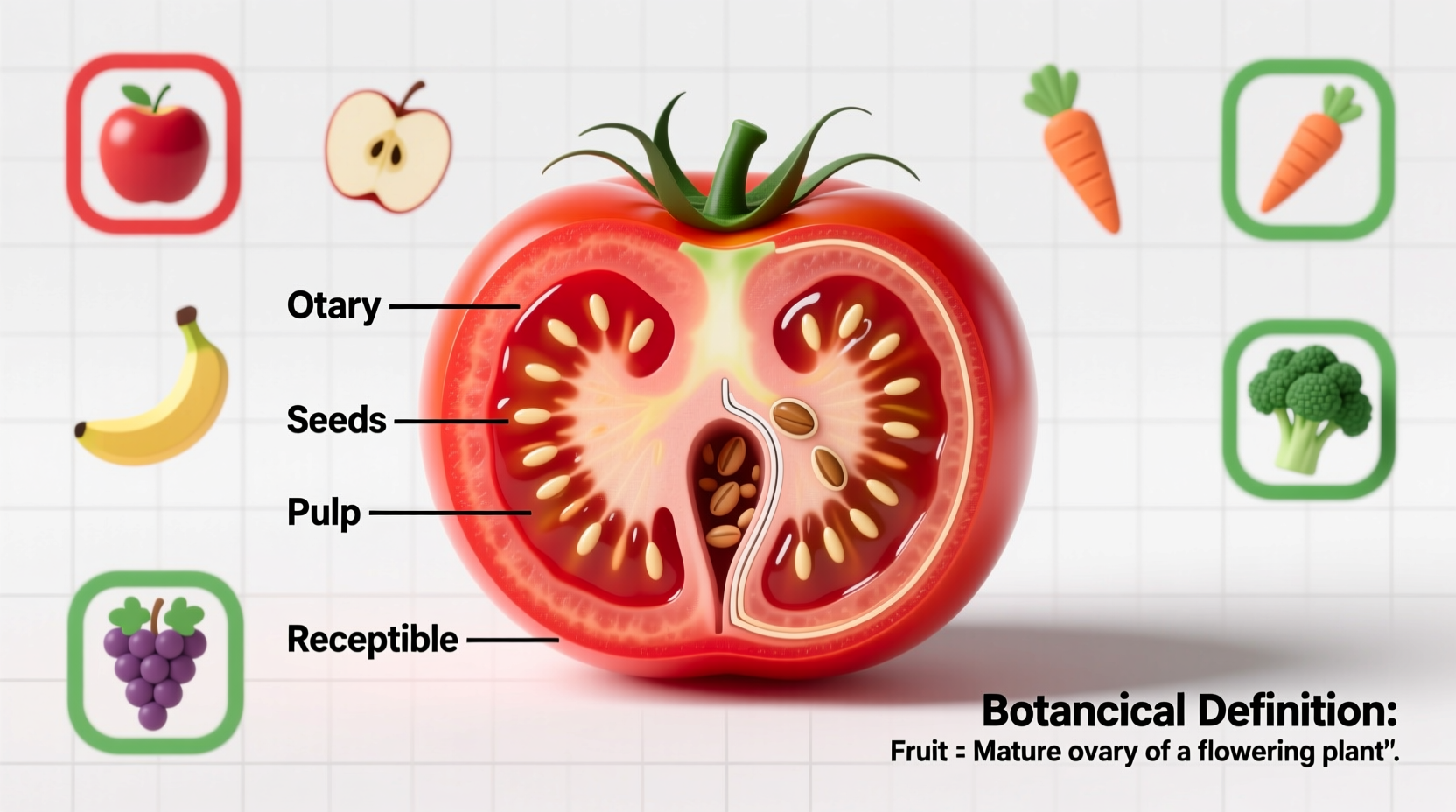

When you bite into a ripe tomato, you're enjoying what science unequivocally defines as a fruit. This classification isn't arbitrary—it's based on strict botanical criteria that have been consistent for centuries. Unlike culinary classifications which focus on taste and usage, botanical classification examines plant structure and development.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, a fruit is "the mature ovary of a flowering plant, usually containing seeds." Tomatoes perfectly fit this definition. They develop from the fertilized flower of the tomato plant (Solanum lycopersicum), with the ovary wall becoming the fleshy part we eat, all while protecting the seeds inside.

Why the Confusion? Botanical vs. Culinary Classification

The disconnect between scientific classification and everyday understanding creates widespread confusion. Here's where the two perspectives diverge:

| Classification System | Definition of Fruit | Tomato Status |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical | Structure developing from flower ovary containing seeds | Fruit |

| Culinary | Sweet-tasting plant product typically used in desserts | Vegetable |

| Legal (US) | Determined by common usage in meals | Vegetable |

A Landmark Legal Decision: Nix v. Hedden (1893)

The tomato's classification confusion reached the highest court in the United States. In 1893, the Supreme Court case Nix v. Hedden determined that tomatoes should be classified as vegetables for tariff purposes. Justice Horace Gray wrote in the unanimous decision:

"Botanically speaking, tomatoes are the fruit of a vine, just as are cucumbers, squashes, beans, and peas. But in the common language of the people, all these are vegetables which are grown in gardens, and which, whether eaten cooked or raw, are, like potatoes, carrots, parsnips, turnips, beets, cauliflower, cabbage, celery, and lettuce, usually served at dinner in, with, or after the soup, fish, or meats which constitute the principal part of the repast, and not, like fruits, generally as dessert."

This legal distinction, documented in the U.S. Supreme Court archives, created the enduring misconception that tomatoes aren't fruits. The ruling applied specifically to tariff classification, not scientific categorization, but the distinction has persisted in popular understanding.

Tomato's Journey: From Fruit to Vegetable in Public Perception

| Time Period | Tomato Classification | Key Developments |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-16th century | Wild fruit in South America | Grown as ornamental plant in Europe due to perceived toxicity |

| 18th century | Gradually accepted as edible | First culinary recipes appear in European cookbooks |

| 1893 | Legally classified as vegetable | Nix v. Hedden Supreme Court decision |

| Modern era | Scientifically fruit, culinarily vegetable | USDA includes tomatoes in vegetable food group for nutritional guidance |

When the Distinction Actually Matters

Understanding whether tomatoes are fruits or vegetables isn't just academic—it has practical implications:

- Gardening practices: As fruits, tomatoes require similar growing conditions to other fruiting plants, including proper pollination and ripening processes

- Nutritional understanding: While classified as vegetables in dietary guidelines, tomatoes share nutritional characteristics with fruits, particularly high vitamin C content

- Culinary applications: Knowing tomatoes are fruits explains why they pair well with other fruits in certain dishes (like tomato-watermelon salads)

- Food science: The fruit classification affects how tomatoes behave in preservation, as their acidity level differs from true vegetables

According to research from USDA Agricultural Research Service, tomatoes contain citric and malic acids that give them their characteristic tang—chemical properties more common in fruits than vegetables. This acidity level (pH 4.3-4.9) is why tomatoes can be safely canned using water bath methods unlike most vegetables.

Common Misconceptions About Tomato Classification

Several persistent myths surround tomatoes and their classification:

- "If it's a fruit, it must be sweet": Many fruits aren't sweet (cucumbers, peppers, eggplants), while some vegetables can be quite sweet (carrots, beets)

- "Botanical classification determines culinary use": Culinary traditions develop independently from scientific classification

- "The Supreme Court ruling changed the botanical classification": The court only addressed tariff classification, not scientific reality

- "All fruits have high sugar content": Tomatoes contain only 2.6g of sugar per 100g, compared to 10g in apples and 12g in bananas

Other Foods With Similar Classification Confusion

Tomatoes aren't alone in this botanical-culinary disconnect. Many common foods share this dual identity:

- Cucumbers (botanical fruits)

- Zucchini and other squash (botanical fruits)

- Peppers (botanical fruits)

- Eggplants (botanical fruits)

- Pumpkins (botanical fruits)

- String beans (botanical fruits)

Conversely, some foods commonly thought of as vegetables are actually roots (carrots, beets), stems (celery, asparagus), or leaves (lettuce, spinach)—none of which qualify as fruits botanically.

Practical Takeaways for Home Cooks and Gardeners

Understanding the fruit classification of tomatoes can improve your cooking and gardening:

- Store tomatoes at room temperature away from direct sunlight—they continue ripening after harvest like other fruits

- Don't refrigerate tomatoes unless absolutely necessary, as cold temperatures destroy flavor compounds

- When preserving, treat tomatoes like fruits due to their acidity level

- In gardening, provide support for tomato plants as they grow heavy fruit

- Rotate tomato crops annually to prevent soil-borne diseases common in fruiting plants

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4