For centuries, the humble potato has been a dietary cornerstone across the globe, but its journey began high in the Andes where ancient civilizations first cultivated this versatile tuber. Understanding where potatoes originally come from isn't just a historical curiosity—it reveals how this single crop transformed global agriculture, nutrition, and even population dynamics.

The Andean Birthplace of Potatoes

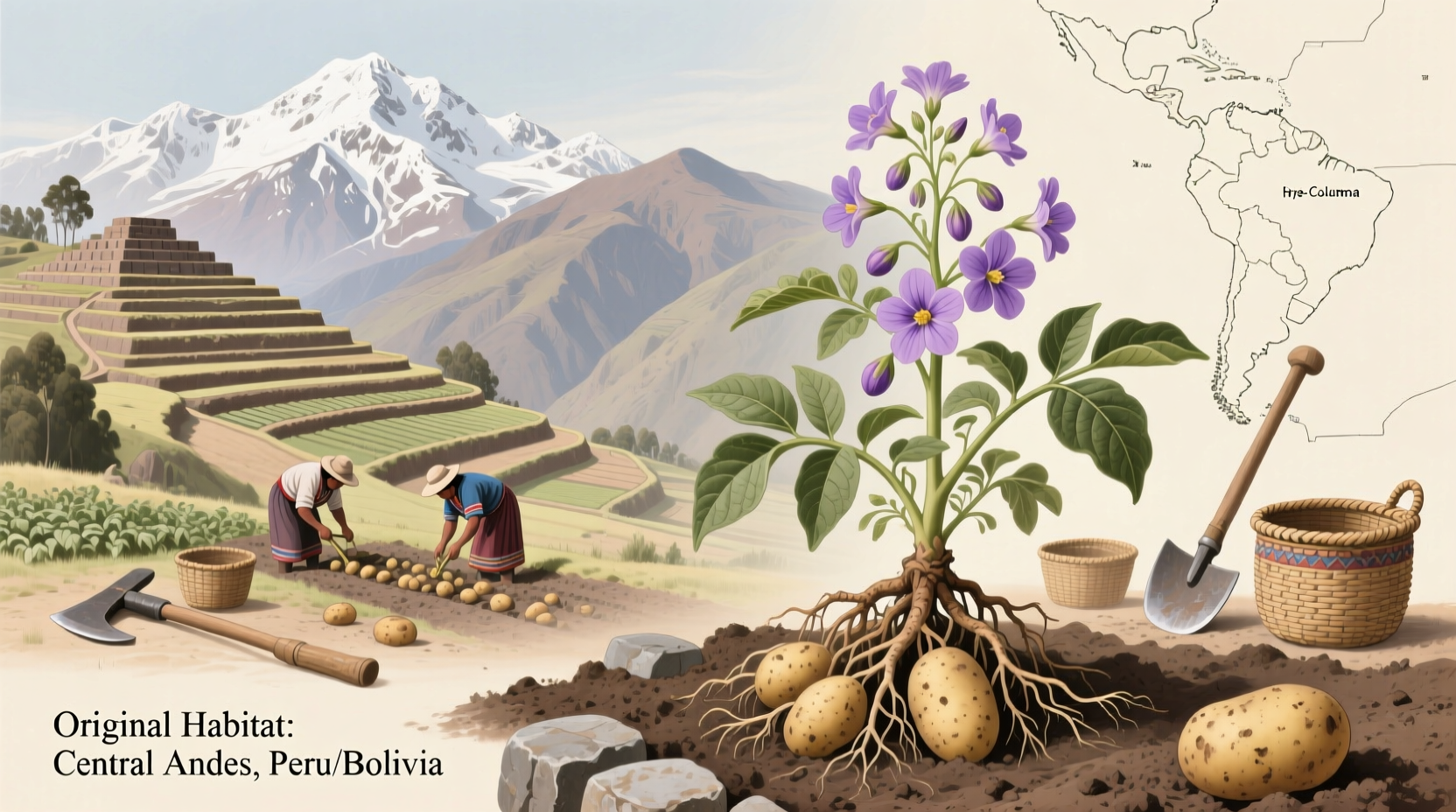

Archaeological evidence confirms that potatoes were first domesticated between 7,000 and 10,000 years ago in the region surrounding Lake Titicaca, which straddles the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia. Indigenous peoples in this high-altitude environment developed sophisticated agricultural techniques to cultivate over 4,000 distinct potato varieties adapted to different microclimates and elevations.

These early farmers mastered the art of chacra (traditional Andean farming), creating terraced fields that maximized limited arable land while preventing soil erosion. They developed freeze-drying techniques to preserve potatoes as chuño, allowing storage for years—a critical adaptation in the unpredictable mountain climate.

Scientific Evidence of Potato Origins

Modern genetic research has confirmed the Andean origin theory through DNA analysis of both wild and cultivated potato species. The International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru maintains the world's largest collection of potato varieties, with over 7,000 accessions that provide crucial evidence for tracing potato evolution.

| Evidence Type | Key Findings | Source Institution |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeological | Potato remnants dating to 2,800 BCE found at sites near Lake Titicaca | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Genetic | Closest wild relative is Solanum brevicaule, native to southern Peru | International Potato Center |

| Linguistic | Quechua word "papa" predates Spanish contact | Andean Language Institute |

Timeline of Potato Domestication and Global Spread

The journey of potatoes from obscure Andean tuber to global staple followed a precise historical trajectory:

- 8,000-10,000 BCE: Initial domestication by indigenous peoples in the Andes

- 2,800 BCE: Archaeological evidence of potato cultivation near Lake Titicaca

- 1530s: Spanish conquistadors encounter potatoes during South American expeditions

- 1570: First documented introduction of potatoes to Europe

- 1700s: Potatoes become staple crop across Europe, particularly Ireland

- 1845-1852: Irish Potato Famine demonstrates global dependence on this single crop

- Present: Potatoes rank as the world's fourth largest food crop after maize, wheat, and rice

How Potatoes Transformed Global Agriculture

The introduction of potatoes to Europe in the 16th century triggered profound demographic and agricultural changes. Unlike traditional European grains, potatoes provided exceptional nutritional value per acre—delivering more calories, protein, and vitamin C than wheat or barley. Historical research published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics demonstrates that regions adopting potatoes experienced significant population growth between 1700-1900.

However, this global spread came with limitations. European farmers initially grew only a few varieties, creating genetic vulnerability that culminated in the Irish Potato Famine when Phytophthora infestans (potato blight) devastated the genetically uniform crop. This historical lesson underscores why preserving the genetic diversity found in the potato's Andean homeland remains critically important today.

Modern Connections to Ancient Origins

While most commercial potatoes today descend from just a handful of varieties introduced to Europe, the Andes still harbor remarkable potato diversity. In Peru alone, farmers cultivate over 3,000 native varieties with colors ranging from deep purple to golden yellow, each adapted to specific altitudes and soil conditions.

Contemporary agricultural scientists increasingly recognize the value of these traditional varieties. Researchers at the International Potato Center have documented how indigenous Andean farmers maintain "living seed banks" through complex crop rotation systems that preserve genetic diversity while preventing soil depletion. These traditional practices offer valuable insights for developing climate-resilient potato varieties as global temperatures rise.

Why Potato Origins Matter Today

Understanding where potatoes originally come from isn't merely academic—it has practical implications for food security. As climate change threatens traditional potato-growing regions, scientists are returning to the crop's Andean origins to find varieties resistant to drought, frost, and disease.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization recognizes the importance of preserving potato biodiversity, noting that "the genetic resources conserved in the Andes represent the best hope for adapting potatoes to future environmental challenges." By studying ancient cultivation techniques and diverse native varieties, researchers aim to develop more resilient potato crops that can withstand the agricultural challenges of the 21st century.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4