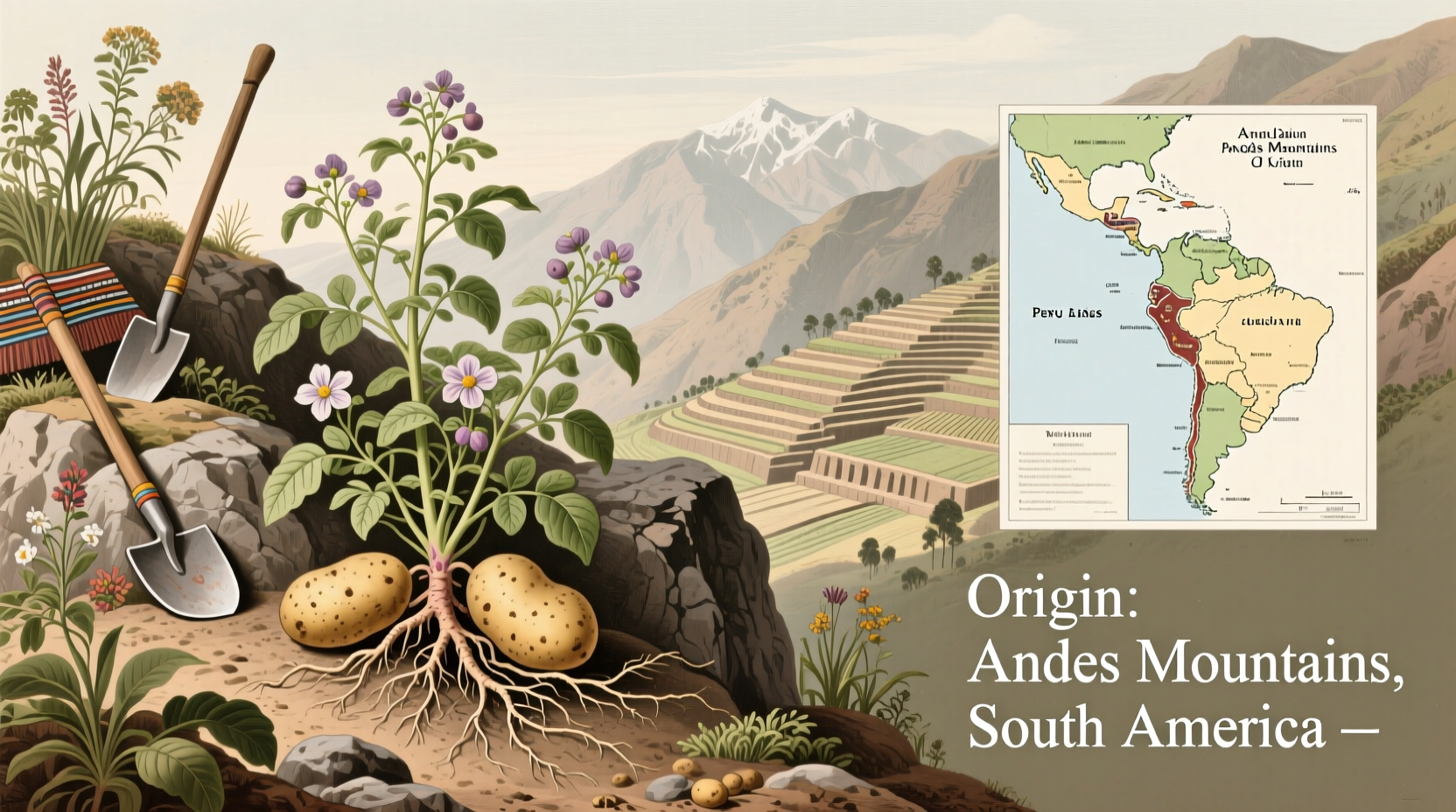

For centuries, the humble potato has fueled civilizations, transformed cuisines, and shaped global agriculture. But where did this versatile tuber actually begin its journey? The answer lies high in the Andes Mountains, where ancient civilizations cultivated the first potatoes long before Europeans ever set foot in the Americas.

The Andean Origins: Where It All Began

Archaeological evidence confirms that potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) were first domesticated in the region surrounding Lake Titicaca, which straddles the border between modern-day Peru and Bolivia. Indigenous communities in this high-altitude environment—living at elevations between 11,000 and 15,000 feet—developed sophisticated agricultural techniques to cultivate over 4,000 varieties of potatoes adapted to diverse microclimates.

These early farmers selectively bred wild potato species, transforming the small, bitter tubers of Solanum brevicaule into the nutrient-rich food source we recognize today. The potato became central to Andean culture, featuring in religious ceremonies and serving as a dietary staple that could withstand the region's challenging growing conditions.

Scientific Evidence: Tracing Potato Lineage

Modern genetic research has pinpointed the exact origin of cultivated potatoes. A landmark 2018 study published in Nature Genetics analyzed the DNA of over 400 potato varieties, confirming that all modern potatoes descend from a single domestication event in southern Peru. Researchers from the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima identified the wild species Solanum candolleanum as the most likely progenitor of today's cultivated potatoes.

| Evidence Type | Discovery Location | Time Period | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaeological Remains | Chilca Canyon, Peru | 6,000-8,000 years ago | Earliest known potato remnants showing domestication |

| Genetic Analysis | Lake Titicaca Basin | 7,000-10,000 years ago | Identified single domestication event from wild ancestors |

| Historical Records | Inca Empire territories | Pre-1532 CE | Documented sophisticated potato storage and freeze-drying techniques |

Timeline of Potato Domestication and Global Spread

The journey from Andean staple to global food crop unfolded through distinct historical phases:

- 8000-5000 BCE: Initial domestication by indigenous communities in the Titicaca region

- 2500 BCE: Development of chuño (freeze-dried potatoes) for long-term storage

- 1438-1533 CE: Inca Empire establishes sophisticated potato cultivation systems across the Andes

- 1532: Spanish conquistadors encounter potatoes during conquest of the Inca Empire

- 1570: First recorded introduction of potatoes to Europe via Spanish ships

- 1719: Potatoes reach North America, brought by Irish immigrants to New Hampshire

- 19th Century: Potato becomes staple crop across Europe and Asia

Why Potato Origins Matter Today

Understanding the potato's Andean origins isn't just historical trivia—it has practical implications for modern agriculture. The genetic diversity preserved in native Andean varieties provides crucial resistance to diseases like late blight, which caused the Irish Potato Famine. Scientists at the International Potato Center regularly collect wild potato specimens from the Andes to breed more resilient commercial varieties.

Climate change poses new challenges that ancient Andean potato varieties may help solve. Traditional varieties like papa nativa can withstand temperature fluctuations and poor soil conditions that would devastate modern commercial strains. This genetic reservoir, developed over millennia by indigenous farmers, represents an invaluable resource for global food security.

Preserving Ancient Knowledge

Today, organizations like the Parque de la Papa (Potato Park) in Peru work with six Quechua communities to preserve over 1,400 native potato varieties. This living museum of agricultural biodiversity demonstrates how traditional knowledge complements modern science. Indigenous farmers continue using ancient techniques like waru waru (raised field agriculture) that regulate soil temperature and moisture—methods now being studied for climate-resilient farming worldwide.

When you bite into a potato today, you're experiencing a food that has sustained Andean communities for thousands of years. From the high plateaus of Peru to kitchens across the globe, the potato's journey represents one of humanity's most successful agricultural partnerships between people and plants.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4