The Botanical Truth: More Than Just a Salad Staple

Despite common kitchen classification, tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are botanically fruits—specifically berries—containing seeds surrounded by fleshy tissue. This scientific reality contrasts with their legal classification as vegetables, established by the 1893 U.S. Supreme Court case Nix v. Hedden for tariff purposes. Understanding this dual identity helps explain why tomatoes function as both culinary vegetables and botanical fruits in different contexts.

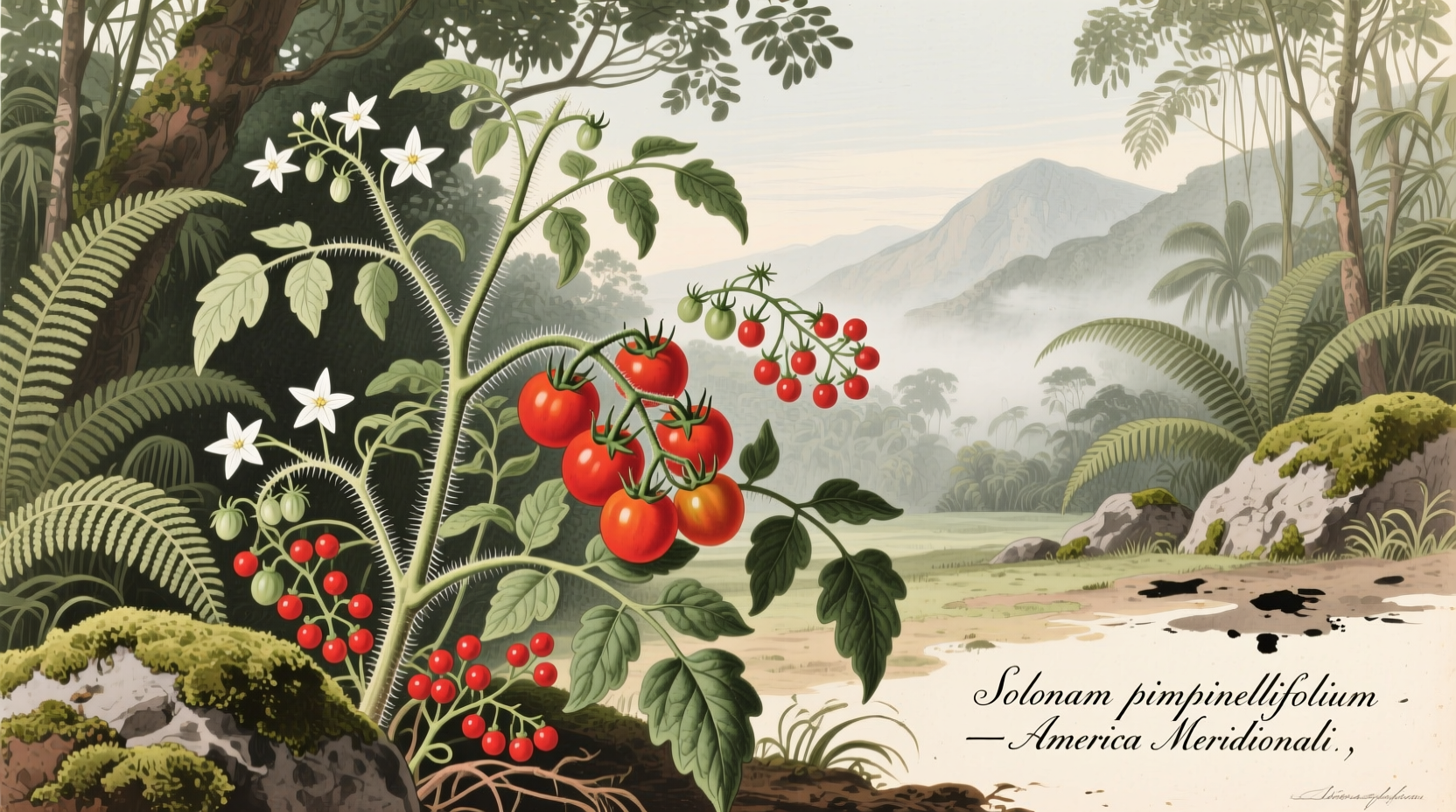

Tracing the Tomato's Journey: From Wild Berry to Global Staple

Wild tomato ancestors grew as small, greenish-yellow fruits in the Andes mountains. Archaeological evidence from Peru shows early cultivation dating back to 800 BCE. The transformation began when indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica selectively bred these wild varieties, creating larger, redder fruits that became integral to Aztec cuisine—used in sauces, stews, and as offerings in religious ceremonies.

| Era | Tomato Status | Key Developments |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-500 BCE | Wild species | Small, greenish fruits growing in Andean regions |

| 500 BCE-1500 CE | Domesticated crop | Mesoamerican civilizations develop larger, redder varieties |

| 1521-1600 | European curiosity | Initially grown as ornamental plants; feared as poisonous |

| 18th-19th century | Global food crop | Italy adopts tomatoes into cuisine; industrial canning begins |

Why Europeans Feared the "Love Apple" for Centuries

When Spanish conquistadors brought tomatoes to Europe in the 1520s, they were initially regarded with suspicion. Many Europeans believed tomatoes were poisonous due to their membership in the nightshade family (Solanaceae), which includes deadly species like belladonna. This misconception persisted for over 200 years, with tomatoes grown primarily as ornamental plants in elite gardens. Historical records from Italy's Tuscany region show tomatoes weren't regularly consumed until the late 17th century, and even then, only by the rural poor.

The Scientific Transformation: From Aztec Xitomatl to Modern Varieties

The word "tomato" derives from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word tomatl, which referred to a different fruit altogether—the husk tomato or tomatillo. Spanish explorers mistakenly applied this name to the red fruit they encountered. Modern genetic research published in Nature Genetics confirms that all cultivated tomatoes descend from a single domestication event in western South America, followed by intensive breeding in Mesoamerica that increased fruit size by 100-fold compared to wild ancestors.

Tomato Cultivation Today: A Global Phenomenon

China now leads global tomato production with approximately 68 million metric tons annually, followed by India and Turkey according to FAO data. The United States Department of Agriculture reports over 150 million tons of tomatoes are produced worldwide each year across 180 countries. Modern breeding has created thousands of varieties—from tiny cherry tomatoes to massive beefsteak types—each adapted to specific climates and culinary uses. Interestingly, the state of Ohio officially designated the tomato as its state fruit in 2000, recognizing its agricultural significance despite the botanical classification debate.

Why Tomato History Matters for Modern Cooks

Understanding tomato origins helps explain flavor variations between heirloom and commercial varieties. Traditional Mexican cooking techniques like roasting tomatoes on comals (clay griddles) before making salsa capitalize on the fruit's natural sugars—a practice rooted in pre-Hispanic culinary traditions. When selecting tomatoes today, knowing their South American heritage explains why they thrive in warm, sunny conditions and why certain heirloom varieties better preserve the complex flavor profiles developed through centuries of indigenous cultivation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4