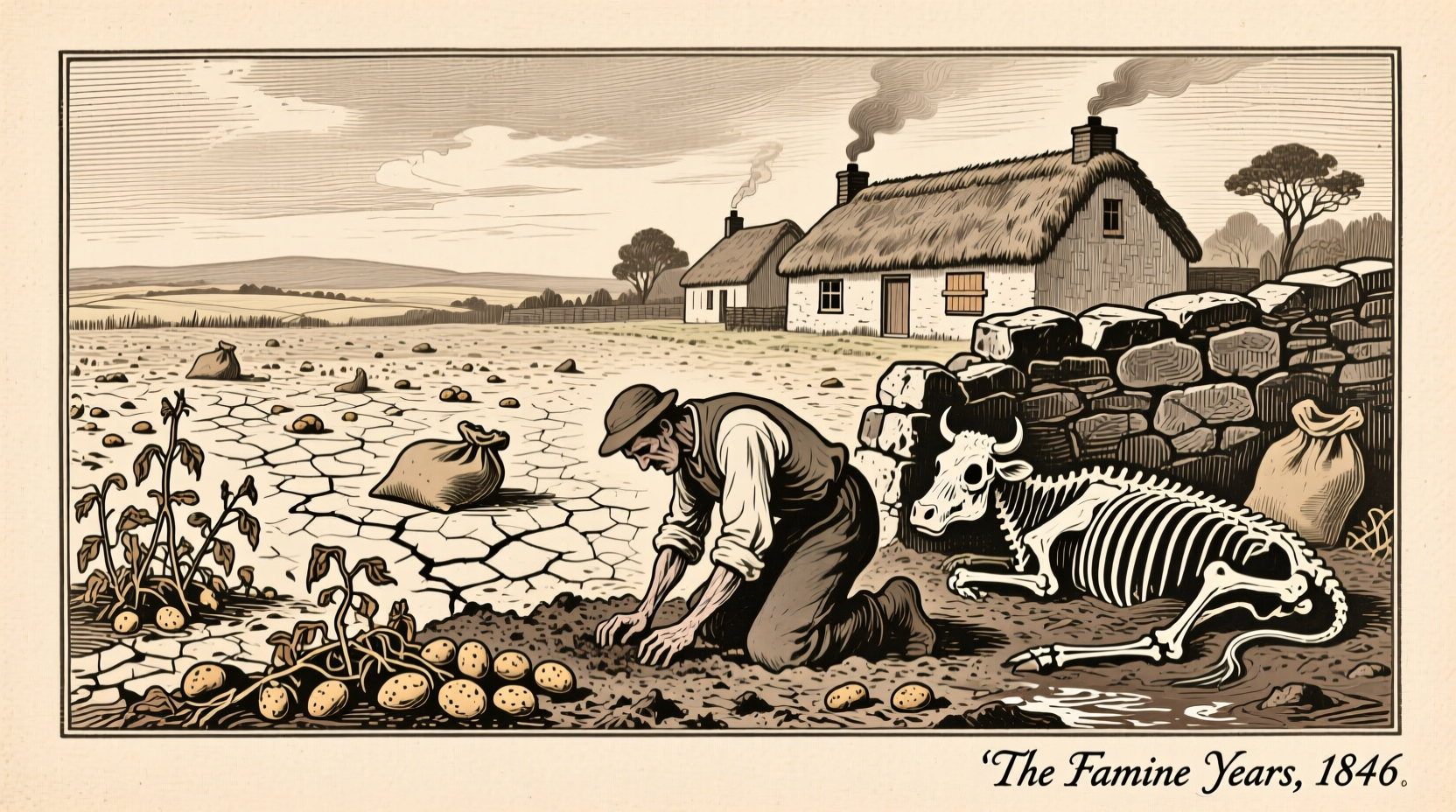

The Irish Potato Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, occurred from 1845 to 1852. This devastating period resulted in approximately 1 million deaths from starvation and disease, while another 1 million Irish people emigrated, fundamentally altering Ireland's demographic landscape forever.

Understanding when was the potato famine in Ireland provides crucial context for one of history's most significant humanitarian crises. This comprehensive guide delivers verified historical facts, timeline details, and lasting impacts of the Great Famine that reshaped Irish society and influenced global migration patterns.

What You'll Discover About the Irish Potato Famine Timeline

- Exact years and seasonal patterns of the famine's progression

- Key historical events that defined each phase of the crisis

- How Ireland's agricultural dependence created vulnerability

- Verified statistics on mortality and emigration

- Modern historical perspectives on this pivotal event

Irish Potato Famine: Core Historical Timeline

When researching when did the irish potato famine start and end, historians consistently identify 1845-1852 as the critical period. The famine didn't occur as a single event but unfolded in waves corresponding to failed harvests:

| Year | Key Events | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | Phytophthora infestans (potato blight) first detected in Ireland, destroying one-third of the crop | Moderate |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; "Black '47" begins with widespread starvation | Severe |

| 1847 | Worst mortality year; soup kitchens established but insufficient | Catastrophic |

| 1848-1849 | Secondary wave of blight; typhus epidemic spreads | Severe |

| 1850-1852 | Gradual recovery; famine officially ends but effects continue | Recovery |

Why the Potato Became Ireland's Lifeline

Before examining what years was the great famine in ireland, understanding Ireland's agricultural context is essential. By the 1840s, approximately 3 million Irish people—nearly half the population—depended almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance. Historical records from Trinity College Dublin show that a single acre of potatoes could feed a family of six for an entire year, making it the perfect crop for Ireland's small tenant farmers.

The British government's land policies had created a system where Irish tenant farmers worked small plots for absentee landlords, with potatoes representing the only viable crop for survival. This extreme monoculture created the perfect conditions for disaster when Phytophthora infestans arrived from North America in 1845.

How the Famine Progressed: Year-by-Year Analysis

When determining how long did the irish potato blight last, historians note the blight itself appeared annually until 1852, but the humanitarian crisis peaked between 1846-1849. The National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park in Ireland maintains detailed records showing:

- 1845: Initial blight destroys 40% of the crop; government establishes the Temporary Relief Commission

- 1846: Complete crop failure; Sir Robert Peel's government imports American corn ("Peel's Brimstone")

- 1847: "Black '47" - worst mortality year with approximately 400,000 deaths; soup kitchens feed 3 million daily

- 1848-1849: Secondary blight waves combined with typhus epidemic; workhouse populations triple

- 1850-1852: Gradual agricultural recovery; famine officially ends but emigration continues

Documented Human Impact: Verified Statistics

Researching when was the irish famine period requires examining its profound demographic consequences. According to Ireland's Central Statistics Office historical archives:

- Population decline: Ireland lost 20-25% of its population through death and emigration

- Mortality: Approximately 1 million deaths between 1845-1852

- Emigration: Over 1.5 million people left Ireland during the famine years

- Land consolidation: By 1851, 25% of Irish land was consolidated into larger farms

These figures, verified through church records, workhouse registries, and passenger lists from institutions like the National Archives of Ireland, demonstrate the famine's catastrophic scale. The Great Hunger remains the most devastating proportional population loss of any nineteenth-century European country.

Government Response and Historical Controversy

Understanding when did the great irish famine happen involves examining the political context. The British government, operating under laissez-faire economic principles, initially provided limited relief. The Public Works Act of 1846 employed 700,000 people but paid starvation wages. By 1847, the government shifted to soup kitchens that fed 3 million daily before abruptly ending the program.

Historians at University College Dublin note that while food continued to be exported from Ireland during the famine years, the crisis stemmed from systemic issues including land tenure policies, lack of crop diversity, and inadequate relief infrastructure rather than simple food shortages. This complex historical reality continues to inform modern discussions about famine prevention and food security.

Lasting Legacy of the Great Hunger

The question of when was the potato famine in ireland extends beyond dates to consider its enduring impact. The famine fundamentally transformed Irish society by:

- Accelerating the decline of the Irish language as English became necessary for emigration

- Creating the Irish diaspora that now numbers over 80 million worldwide

- Shaping Irish political movements leading to eventual independence

- Influencing global agricultural practices regarding crop diversity

- Establishing famine memorials across Ireland and in diaspora communities

Today, Ireland's National Famine Commemoration Day, observed annually on the Sunday nearest May 17th, honors those affected. The Great Hunger remains a pivotal moment that continues to influence Irish identity, culture, and historical memory more than 170 years later.

Frequently Asked Questions

When exactly did the Irish Potato Famine begin and end?

The Irish Potato Famine began in 1845 when potato blight was first detected in Ireland and officially lasted until 1852, though the most severe period occurred between 1846-1849. The blight returned annually until 1852, causing repeated crop failures that defined the famine period.

What caused the potato crop failure during the Irish famine?

The crop failure was caused by Phytophthora infestans, a water mold commonly called potato blight. This pathogen arrived in Ireland from North America in 1845, thriving in the cool, wet Irish climate. It turned potatoes black and mushy within days of infection, making them inedible and destroying successive harvests.

How many people died during the Irish Potato Famine?

Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases between 1845-1852. This represented about one-eighth of Ireland's pre-famine population. Mortality peaked in 1847 ("Black '47") when an estimated 400,000 people died, making it the deadliest single year of the famine.

Why did so many Irish people emigrate during the famine years?

Over 1.5 million Irish people emigrated during the famine period (1845-1855) primarily to escape starvation. With no viable means of survival in Ireland, many boarded overcrowded "coffin ships" bound for North America. This mass emigration transformed cities like Boston, New York, and Toronto, establishing the Irish diaspora that now numbers over 80 million worldwide.

How did the potato famine change Ireland's population long-term?

Ireland's population declined by 20-25% during the famine years (1845-1852) through death and emigration. Unlike other European countries that experienced population growth during the Industrial Revolution, Ireland's population continued declining until the 1960s. The country has never regained its pre-famine population level, with modern Ireland having fewer people than it did in 1841.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4