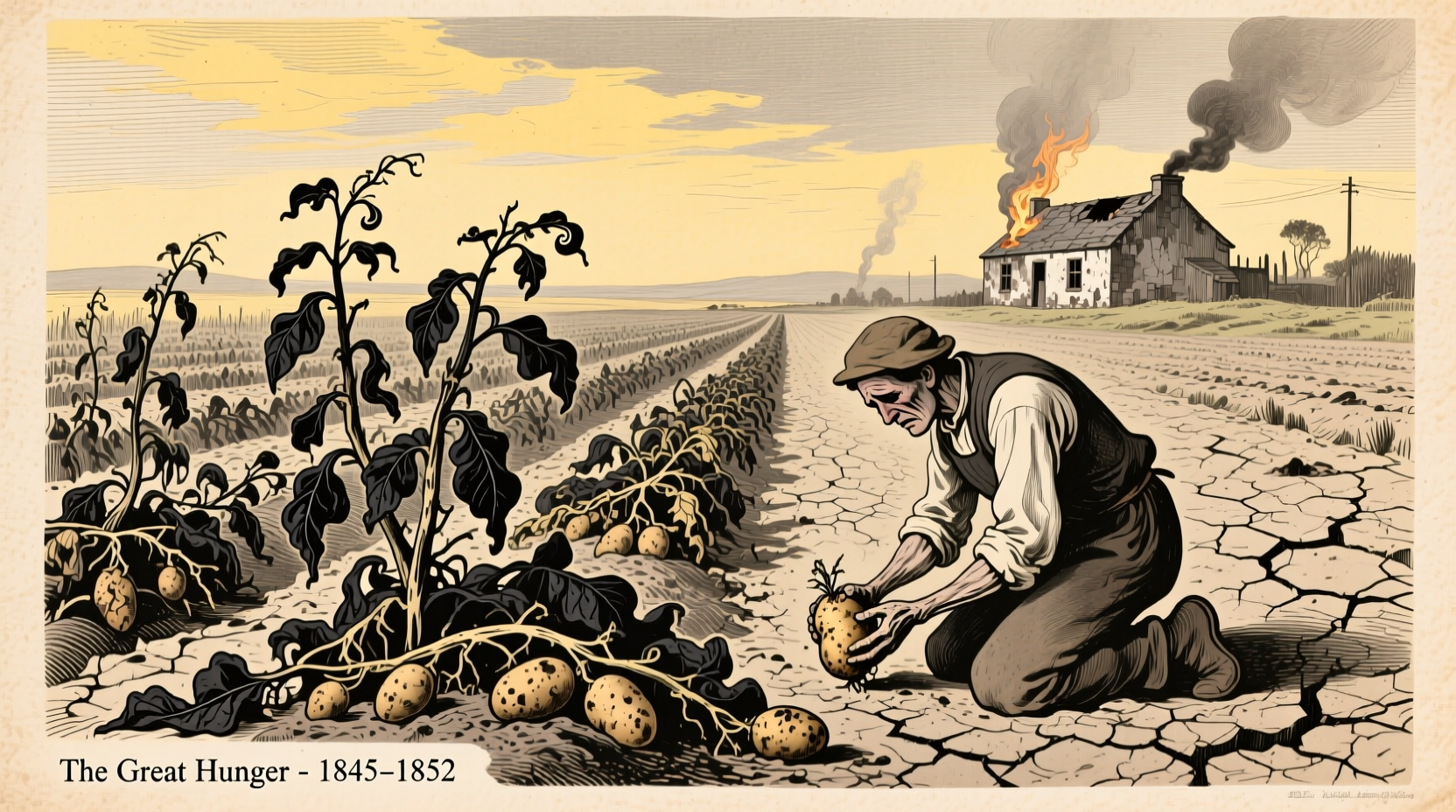

The Irish Potato Famine, also known as the Great Famine or An Gorta Mór, occurred from 1845 to 1852. This devastating period resulted in approximately 1 million deaths and triggered mass emigration that permanently altered Ireland's demographic landscape.

Understanding the Irish Potato Famine: A Historical Timeline You Need to Know

When searching for when was the potato famine, you're likely seeking not just dates but context about one of history's most catastrophic food crises. This article delivers precise historical facts while exploring the complex factors that made the Irish Potato Famine a defining moment in 19th century history.

Why the Potato Famine Matters Today

Understanding when did the irish potato famine happen provides crucial insights into how food dependency, colonial policies, and climate events can combine to create humanitarian disasters. The famine's legacy continues to influence Irish identity, diaspora communities worldwide, and modern approaches to food security.

The Historical Context: Ireland's Dependence on the Potato

Prior to the famine, approximately 3 million Irish people—nearly half the population—relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance. This monoculture dependence made Ireland uniquely vulnerable when Phytophthora infestans, a destructive water mold, arrived from North America in 1845.

The first blight appeared in September 1845 near Dublin. Within weeks, it spread across the country, turning healthy potato crops black and inedible. Successive failures through 1846-1849 created the prolonged crisis that defines the irish potato famine timeline.

Key Events in the Potato Famine Timeline

Understanding how long did the potato famine last requires examining its phased development. This verified timeline shows the progression of events:

| Year | Key Events | Documented Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | First appearance of potato blight in Ireland | One-third of potato crop destroyed |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; "Black 47" begins | Widespread starvation; workhouse populations surge |

| 1847 | "Black 47" - worst famine year | Approximately 400,000 deaths; mass emigration begins |

| 1848-1849 | Repeated crop failures; typhus epidemic | Additional 200,000+ deaths; peak emigration |

| 1850-1852 | Gradual recovery; lingering effects | Population decline continues through emigration |

Source: National Famine Museum, Strokestown Park, Ireland (strokestownpark.ie/famineArchive/)

Regional Variations in Famine Impact

While researching when was the great famine, it's essential to recognize that impact varied significantly across Ireland. The western and southern regions experienced the most severe consequences due to:

- Higher concentration of small tenant farmers dependent on potatoes

- Less access to alternative food sources

- More challenging transportation infrastructure

- Greater absentee landlord presence

Conversely, Ulster and eastern regions saw comparatively less severe effects due to more diversified agriculture and stronger industrial employment opportunities. This regional disparity explains why irish potato famine death toll estimates vary between historical accounts.

According to research from University College Dublin's School of History (ucd.ie/irishfamine/), counties like Cork, Kerry, and Mayo lost over 25% of their population through death and emigration, while Dublin and surrounding areas experienced losses closer to 10%.

Why the Famine Lasted Seven Years: Contributing Factors

The question how long did the potato famine last reveals important historical complexities. While the initial blight appeared in 1845, the crisis persisted until 1852 due to several interconnected factors:

- Repeated crop failures: Blight returned annually through 1849, preventing recovery

- Inadequate relief efforts: British government policies limited effective intervention

- Export paradox: Ireland remained a net food exporter during the famine

- Disease: Typhus, cholera, and dysentery spread among malnourished populations

- Structural issues: Land tenure system and absentee landlordism worsened vulnerability

Measuring the Famine's Human Cost

Historians continue to refine estimates of the irish potato famine casualties using modern demographic techniques. Current scholarly consensus indicates:

- Approximately 1 million deaths directly attributable to famine conditions

- Another 1-2 million people emigrated between 1845-1855

- Ireland's population declined by 20-25% during this period

- Population never recovered to pre-famine levels (8.2 million in 1841)

These figures represent one of the most severe demographic collapses in European history relative to population size. The National Archives of Ireland (nationalarchives.ie) maintains extensive records documenting individual experiences during this period.

Legacy of the Great Hunger

The question when did the irish famine end has both a specific answer (1852) and a more complex historical reality. While the immediate crisis subsided by 1852, the famine's consequences continue to shape Ireland and its global diaspora:

- Permanent population decline: Ireland remains the only European country with a smaller population today than in 1840

- Diaspora formation: Over 80 million people worldwide claim Irish ancestry, largely due to famine emigration

- Cultural trauma: The famine remains a central element in Irish historical consciousness

- Policy changes: Led to significant reforms in land ownership and agricultural practices

Understanding the precise great famine irish timeline helps contextualize these lasting impacts. The famine wasn't merely a natural disaster but the result of complex interactions between environmental factors, economic policies, and social structures.

Common Misconceptions About the Potato Famine

When exploring when was the potato famine in ireland, several persistent myths require clarification:

- Myth: The famine was caused solely by potato blight

Reality: While blight triggered the crisis, political and economic factors determined its severity - Myth: The British government did nothing

Reality: Relief efforts existed but were inadequate and often counterproductive - Myth: All Irish people ate only potatoes

Reality: The poorest tenant farmers were most dependent on potatoes - Myth: The famine ended when the blight disappeared

Reality: Recovery took years after the last blight outbreak

Learning More About This Pivotal Historical Event

For those seeking deeper understanding of when did the potato famine start and end, numerous authoritative resources exist beyond basic irish potato famine dates. The Great Famine remains one of history's most extensively documented humanitarian crises, offering valuable lessons about food security, governance during emergencies, and resilience in the face of catastrophe.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4