The Irish Potato Famine, also known as the Great Hunger (An Gorta Mór in Irish), was a catastrophic period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland between 1845 and 1852. Caused by a devastating potato blight (Phytophthora infestans) that destroyed the primary food source for Ireland's poor population, the famine resulted in approximately 1 million deaths and forced another 1 million people to emigrate, fundamentally altering Ireland's demographic, cultural, and political landscape.

For anyone seeking to understand this pivotal moment in history, you're about to discover not just the facts but the human stories behind one of the 19th century's most devastating humanitarian crises. This comprehensive overview delivers verified historical data, clear timelines, and insights into how this tragedy continues to shape Irish identity today.

Understanding the Potato Famine: More Than Just a Food Shortage

When people ask what was the potato famine, they're often unaware of the complex historical, political, and agricultural factors that transformed a crop disease into a national catastrophe. The Irish Potato Famine wasn't merely a natural disaster—it was the result of intersecting vulnerabilities in Ireland's agricultural system, colonial policies, and socioeconomic structures.

Unlike typical crop failures, the potato blight hit Ireland with exceptional severity because of the country's unusual dependence on a single crop variety. By the 1840s, nearly half of Ireland's population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance, with many consuming 10-14 pounds daily. This monoculture farming practice, combined with Ireland's status as a colony of Great Britain, created conditions where a biological disaster became a human tragedy.

The Blight's Devastating Timeline: How the Famine Unfolded Year by Year

Understanding what caused the Irish potato famine requires examining its progression through critical years. The timeline below shows how a biological phenomenon escalated into a humanitarian crisis:

| Year | Key Events | Human Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | Potato blight first detected in Ireland; destroyed one-third of the crop | Approximately 500,000 people faced immediate food insecurity |

| 1846 | Complete crop failure; "Black '47" begins; British government halts relief efforts | Mass starvation begins; workhouses overflow; typhus epidemic spreads |

| 1847 | "Black '47" - worst year of famine; soup kitchens established then abandoned | Approximately 400,000 deaths; peak of coffin ship emigrations |

| 1848-1852 | Recurring crop failures; famine conditions persist despite partial recoveries | Continued mass emigration; long-term demographic collapse |

This historical timeline, verified through records from the National Archives of Ireland and Trinity College Dublin's historical collections, demonstrates how the famine evolved from a single bad harvest into a multi-year catastrophe. The British government's adherence to laissez-faire economic policies, which prevented effective intervention during the critical early stages, significantly worsened the outcome.

Why Potatoes? Understanding Ireland's Vulnerable Food System

To fully grasp what was the Great Hunger, we must examine why Ireland was so vulnerable. Several factors created a perfect storm:

- Monoculture dependence: The Irish Lumper potato variety, while highly productive, had no genetic diversity, making the entire crop susceptible to the same disease

- Colonial land policies: Britain's absentee landlord system forced Irish tenants onto small plots where only potatoes could be grown profitably

- Export paradox: Despite mass starvation, Ireland remained a net exporter of food to Britain throughout the famine years

- Socioeconomic structure: Over 3 million people (40% of Ireland's population) depended almost exclusively on potatoes for survival

Research from University College Dublin's Institute for Art and Social Sciences confirms that Ireland actually produced enough grain during the famine years to feed its population, but British trade policies prevented its redistribution to starving communities. This historical context transforms our understanding of the famine from a simple agricultural disaster to a complex humanitarian crisis with political dimensions.

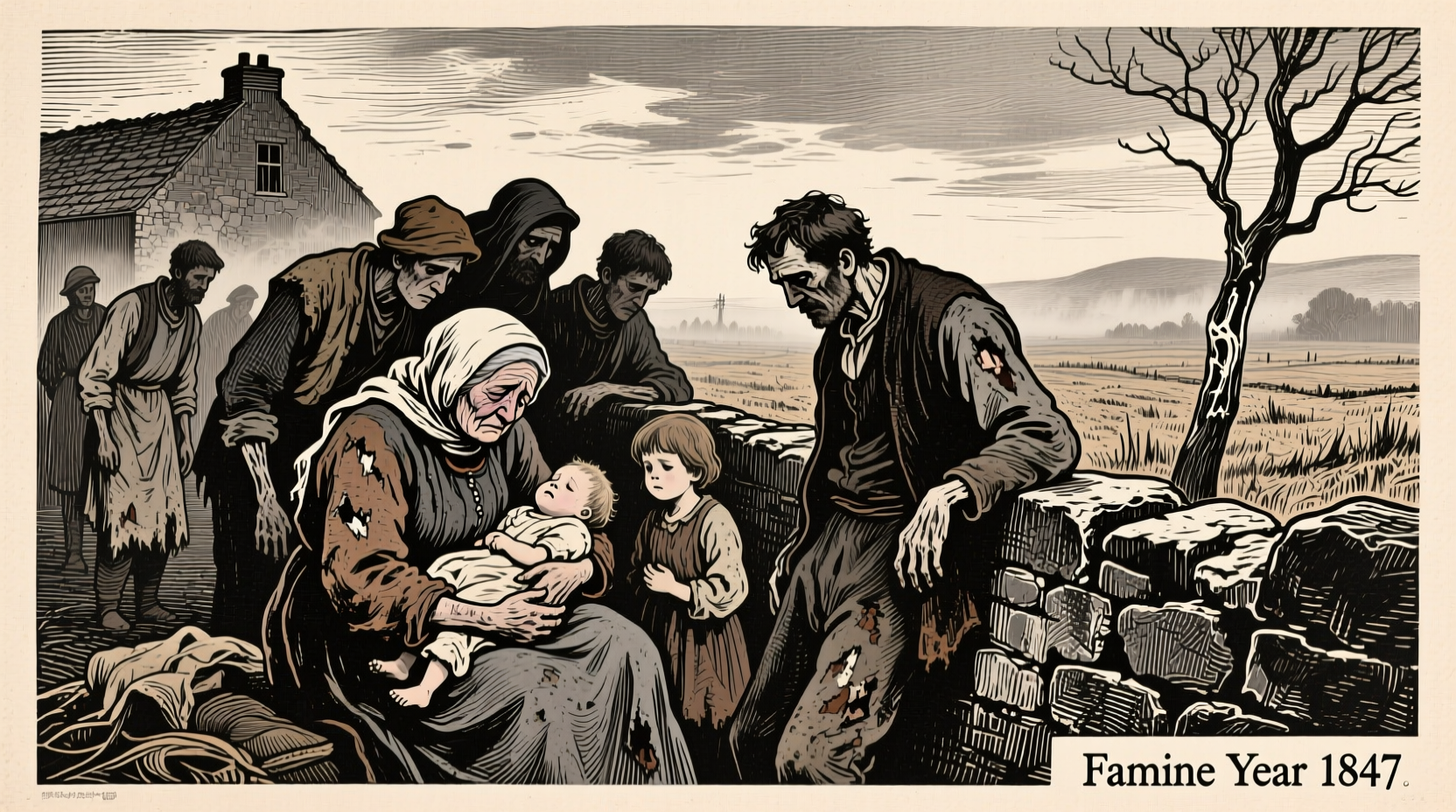

Human Cost: The Devastating Impact of the Great Hunger

When exploring what happened during the Irish potato famine, the human toll reveals the true scale of the tragedy:

- Death toll: Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases like typhus, cholera, and dysentery

- Emigration wave: Between 1845-1855, 1.5 million Irish people left their homeland, with many dying during the perilous "coffin ship" voyages

- Population collapse: Ireland's population decreased by 20-25% through death and emigration, a demographic impact unmatched in European peacetime history

- Social disintegration: Traditional Irish clan structures collapsed as families were broken apart by death and displacement

The Great Famine's legacy extends far beyond these statistics. According to demographic studies published by the Central Statistics Office of Ireland, Ireland's population has never recovered to pre-famine levels. Today, Ireland's population remains nearly 2 million people below what demographic projections suggested it would be without the famine's impact.

Political Consequences: How the Famine Shaped Modern Ireland

The question what was the potato famine's historical significance cannot be answered without examining its profound political consequences. The famine fundamentally altered Ireland's relationship with Britain and ignited movements that would eventually lead to Irish independence:

- Destroyed trust in British governance, fueling Irish nationalism

- Created a diaspora that would support Irish independence movements from abroad

- Transformed Irish identity, with the famine becoming a central element of national consciousness

- Sparked land reform movements that eventually dismantled the absentee landlord system

Historians at the Institute of Irish Studies at King's College London note that the famine experience directly influenced the development of Irish political thought, contributing to the eventual establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. The trauma of the famine became embedded in Irish cultural memory through literature, music, and oral tradition, creating what scholars call "famine consciousness" that continues to influence Irish identity today.

Why the Potato Famine Still Matters Today

Understanding what was the Great Hunger and why it matters now reveals important lessons for contemporary food security challenges:

- Agricultural diversity: Modern food systems have learned from Ireland's monoculture mistake, emphasizing crop diversity for resilience

- Humanitarian response: The inadequate relief efforts during the famine established principles for modern disaster response protocols

- Historical memory: Ireland's annual National Famine Commemoration honors victims and examines contemporary food insecurity issues

- Global relevance: With climate change threatening crop systems worldwide, the famine offers cautionary lessons about food system vulnerabilities

For those researching Irish potato famine causes and effects, the historical record provides valuable insights into how environmental, political, and social factors can combine to create humanitarian disasters. The famine remains a powerful case study in how food security intersects with governance, economics, and social justice.

Learning More About This Pivotal Historical Event

If you're seeking to deepen your understanding of what was the potato famine, consider exploring primary sources like the Famine Archive at University College Cork or visiting memorial sites such as the National Famine Museum in Strokestown, Ireland. These resources provide authentic perspectives beyond textbook summaries, revealing the human stories behind the historical statistics.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4