Understanding what started the potato famine requires examining both the immediate biological cause and the complex historical conditions that turned a crop disease into a national catastrophe. While Phytophthora infestans was the direct trigger, Ireland's extreme dependence on a single potato variety, combined with British colonial policies and socioeconomic structures, created the perfect conditions for disaster.

The Biological Trigger: Potato Blight Arrives

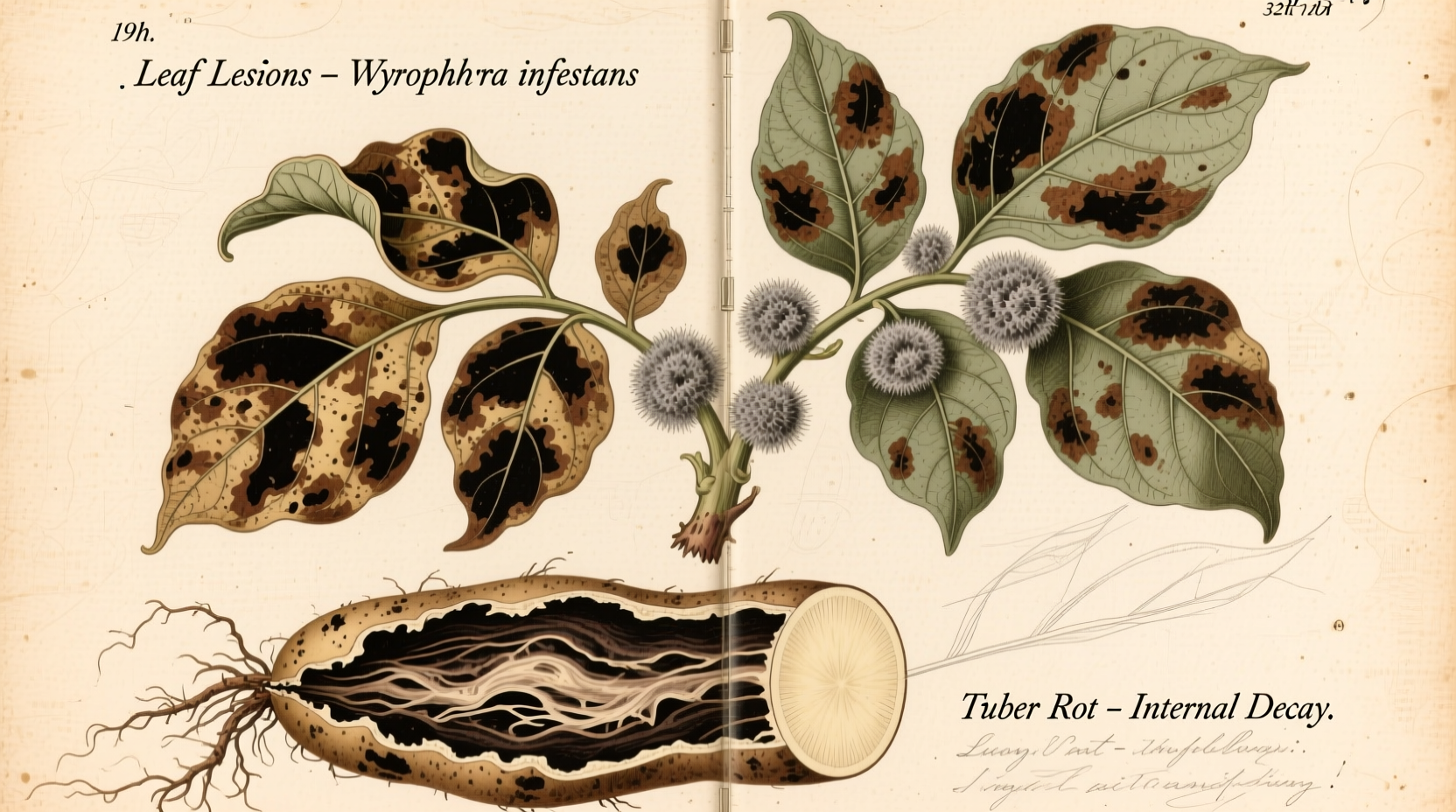

In August 1845, farmers across Ireland noticed their potato plants suddenly wilting. Leaves developed mysterious dark spots, stems blackened, and underground tubers rotted in the ground. Within weeks, entire fields were destroyed. This was Phytophthora infestans, a water mold (not a true fungus) that likely originated in South America and spread to Europe through trade routes.

Unlike previous crop failures, this pathogen spread with unprecedented speed and severity. The cool, damp Irish climate provided ideal conditions for the mold to reproduce and spread. By September 1845, approximately 40% of Ireland's potato crop had been destroyed, with nearly total losses occurring in subsequent years.

| Year | Crop Loss | Estimated Deaths | Key Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 40% | 30,000 | Blight first detected; inadequate government response |

| 1846 | 90-100% | 250,000 | "Black '47" begins; mass evictions; soup kitchens established |

| 1847 | 75% | 400,000 | "Black '47" peak; workhouse system overwhelmed |

| 1848-1852 | Variable | 300,000 | Gradual recovery; mass emigration continues |

Why Was Ireland So Vulnerable?

The devastating impact of the blight stemmed from Ireland's unique agricultural and socioeconomic conditions:

- Monoculture dependence: Over one-third of Ireland's population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance, with many consuming 8-14 pounds daily

- Land tenure system: Most Irish farmers were tenant farmers on absentee British-owned estates, paying rent through cash crops while subsisting on potatoes

- Lack of crop diversity: The Irish Lumper potato variety dominated cultivation but had no resistance to blight

- Export paradox: Despite the famine, Ireland remained a net exporter of food to Britain throughout the crisis

British Policy and the Escalation of Crisis

While the blight initiated the famine, British government policies significantly worsened its impact. The doctrine of laissez-faire economics guided the initial response, with Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel's government reluctant to interfere with market forces. Though Peel did arrange for secret purchases of maize from the United States, the quantity was insufficient and the unfamiliar grain required processing that many starving Irish couldn't manage.

The situation deteriorated further under Lord John Russell's administration, which:

- Maintained the export of grain and livestock from Ireland to Britain

- Insisted on workhouse-based relief that required recipients to give up their land

- Ended direct food aid in 1847, replacing it with inadequate public works programs

- Failed to ban exports despite widespread starvation

According to historical records from the UK National Archives, over 4,000 ships carried food from Ireland to England during the famine years, while the Irish starved. This policy reflected the prevailing belief among British officials that the famine was divine punishment for Irish "moral failings" and an opportunity to modernize Irish agriculture.

Common Misconceptions About the Potato Famine

Several persistent myths obscure the true causes of the famine:

| Misconception | Historical Reality |

|---|---|

| The potato famine was purely a natural disaster | While blight triggered it, policy decisions turned crop failure into mass starvation |

| Ireland had no food during the famine | Ireland remained a net food exporter throughout the crisis |

| The British government did nothing | Policies were implemented but were often counterproductive or insufficient |

| Only potatoes were affected | Other crops grew normally but were exported or inaccessible to the poor |

The Lasting Impact of the Great Hunger

The famine's consequences reshaped Ireland and the world. Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and disease, while another 1 million emigrated, primarily to North America. Ireland's population never recovered, declining from 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.6 million by 1851, and continuing to fall for decades.

The trauma of the famine created deep political resentment that fueled Irish nationalism and eventually contributed to Ireland's independence movement. In the United States, famine refugees formed the foundation of large Irish-American communities that would significantly influence American politics and culture.

Modern historians like Dr. Christine Kinealy, director of Cranaghan Irish Institute at The Catholic University of America, emphasize that understanding what started the potato famine requires examining both the biological trigger and the political context that transformed a crop disease into a demographic catastrophe.

Why This History Matters Today

The Irish Potato Famine offers critical lessons about food security, colonialism, and government responsibility during crises. Modern agricultural practices still face challenges with monoculture farming and pathogen vulnerability. The famine demonstrates how socioeconomic factors can transform a natural disaster into a humanitarian catastrophe—a warning relevant to contemporary climate change and food system vulnerabilities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4