Unlock the Secret of Culinary Satisfaction

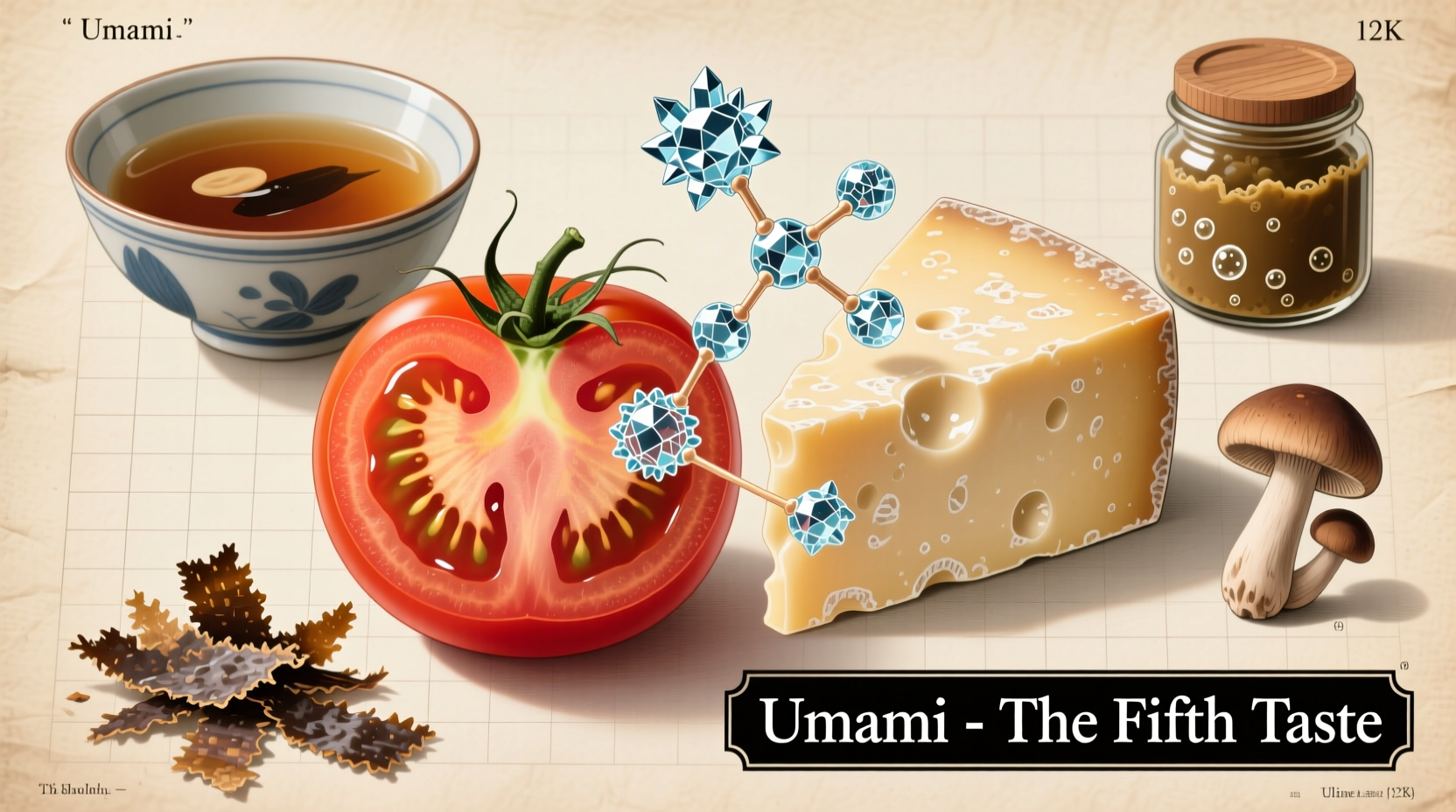

Understanding what is umami taste transforms how you experience food. This essential taste element—the fifth basic taste alongside sweet, sour, salty, and bitter—creates that deep, satisfying savoriness that makes dishes memorable. When you recognize umami, you'll elevate your cooking and dining experiences by intentionally incorporating this flavor dimension that professional chefs rely on to create balanced, mouthwatering meals.

The Science Behind Umami: More Than Just "Savory"

Umami isn't just "savory"—it's a scientifically verified taste sensation detected by specific glutamate receptors on your tongue. Discovered in 1908 by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, umami comes from glutamate (an amino acid) and ribonucleotides like inosinate and guanylate. These compounds trigger a unique neurological response that creates that satisfying "mouthfeel" and lingering deliciousness.

Unlike the other basic tastes that serve as warning signals (bitter for poison, sour for spoilage), umami signals protein-rich, nutritious foods. Your body literally craves this taste because it indicates valuable nutrition. When glutamate binds to receptors, it sends signals to your brain that enhance flavor perception and stimulate saliva production, preparing your digestive system for protein intake.

| Taste Type | Chemical Trigger | Natural Food Sources | Physiological Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet | Sugars | Fruits, honey | Energy source detection |

| Sour | Acids | Citrus, vinegar | Food ripeness/spoilage indicator |

| Salty | Sodium ions | Seafood, vegetables | Electrolyte balance maintenance |

| Bitter | Alkaloids | Dark greens, coffee | Potential toxin warning |

| Umami | Glutamate, nucleotides | Tomatoes, cheese, mushrooms | Protein/nutrition identification |

Umami's Historical Journey: From Kitchen Discovery to Scientific Recognition

While humans have enjoyed umami-rich foods for millennia, its scientific identification began in 1908 when Professor Kikunae Ikeda of Tokyo Imperial University investigated the distinctive taste of dashi (Japanese seaweed broth). He isolated glutamate from kombu seaweed and named this fifth taste "umami" ("umai" meaning delicious, "mi" meaning taste).

Despite Ikeda's discovery, Western science didn't officially recognize umami as a basic taste until 2000, when researchers at the University of Miami identified specific glutamate receptors on the human tongue. The American Chemical Society formally acknowledged umami in 2009, cementing its status alongside the other four basic tastes.

Everyday Foods Packed with Natural Umami

You likely already enjoy umami-rich foods daily without realizing it. These natural sources contain high levels of glutamate and nucleotides that create that satisfying depth of flavor:

- Aged cheeses (Parmesan, Gouda, Roquefort) - aging increases free glutamate

- Ripe tomatoes - especially sun-dried varieties

- Mushrooms (shiitake, porcini) - contain guanylate

- Seaweed (kombu) - traditional Japanese dashi ingredient

- Soy sauce and fermented products - fermentation releases glutamate

- Meat and fish (especially when cooked) - cooking breaks down proteins into glutamate

The umami content significantly increases through processes like aging, curing, drying, and fermentation. For example, fresh tomatoes contain about 140mg of glutamate per 100g, while sun-dried tomatoes contain over 1,000mg per 100g. Similarly, fresh Parmesan contains minimal glutamate, but aged Parmesan develops substantial amounts through the aging process.

Practical Cooking Applications: Harnessing Umami in Your Kitchen

Understanding umami taste examples transforms your cooking. Professional chefs use umami strategically to create depth without excessive salt. Here's how to apply this knowledge:

Umami layering technique: Combine foods with complementary umami compounds. Glutamate (from tomatoes) plus inosinate (from meat) creates a synergistic effect that multiplies the umami sensation. This explains why tomato-based sauces taste better with meat, and why mushrooms enhance vegetarian dishes.

Context boundaries matter: Umami works best in savory dishes but can overwhelm delicate flavors. In soups and sauces, umami creates body and richness. In grilled meats, it enhances the Maillard reaction flavors. However, adding umami-rich ingredients to sweet desserts typically creates imbalance unless carefully calibrated.

For home cooks, simple umami boosters include adding a Parmesan rind to tomato sauce, including dried mushrooms in vegetable broth, or finishing dishes with a splash of soy sauce. These techniques add complexity without making the dish taste specifically of the umami source.

Debunking Common Umami Misconceptions

Despite growing recognition, several myths persist about umami:

Myth: Umami equals MSG

Reality: While monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a purified form of glutamate that enhances umami, umami itself occurs naturally in countless foods. MSG simply delivers glutamate in concentrated form.

Myth: Umami is just "salty"

Reality: Umami creates a distinct neurological response separate from salt receptors. Scientific studies show umami activates different taste pathways and creates longer-lasting flavor satisfaction.

Myth: Only Asian foods contain umami

Reality: Umami exists globally—think aged European cheeses, Italian sun-dried tomatoes, or American grilled meats. The concept originated in Japan, but the taste sensation is universal.

Experiencing Umami: A Simple Taste Test

Try this experiment to isolate the umami sensation:

- Place a small amount of tomato paste on your tongue

- Notice the initial sweet-tart flavor (from sugars and acids)

- Wait 10-15 seconds as the paste dissolves

- Identify the deep, satisfying savoriness that emerges and lingers

This lingering sensation is umami—the taste that makes you want to keep eating. Unlike other tastes that fade quickly, umami creates that "more please" response that defines craveable foods.

Why Umami Matters for Modern Cooking

Understanding how to describe umami taste gives you a powerful tool for creating balanced, satisfying dishes. In today's health-conscious cooking, umami helps reduce sodium while maintaining flavor depth. Chefs use umami strategically to make plant-based dishes more satisfying and to create complex flavors with fewer ingredients.

As research continues, scientists are discovering umami's role in satiety and nutrition. Studies published in the journal Flavour suggest umami-rich foods may promote feelings of fullness, potentially helping with portion control. This makes understanding umami not just a culinary technique, but a potential component of mindful eating practices.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4