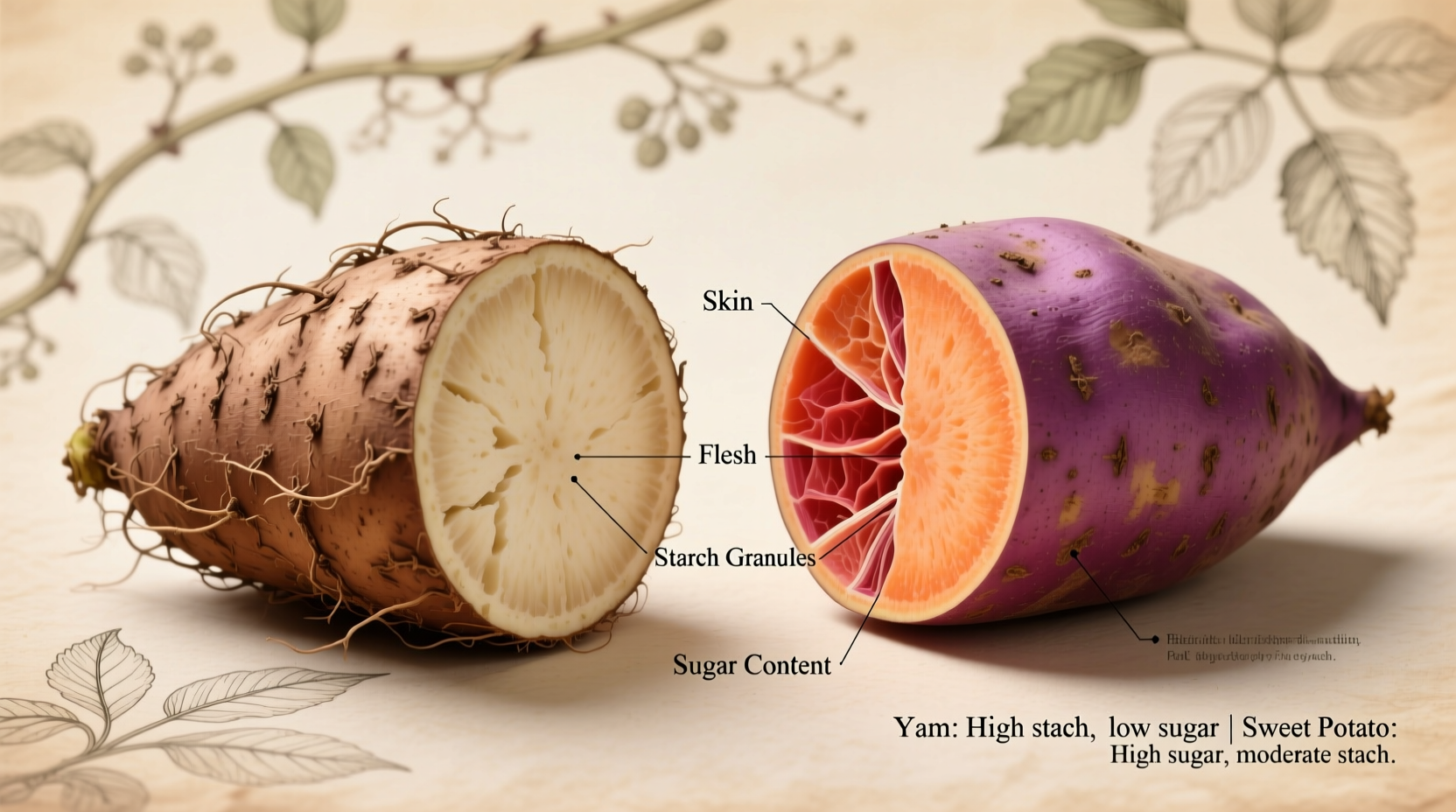

Yams and sweet potatoes are completely different plants: true yams (Dioscorea genus) are starchier, drier tubers native to Africa and Asia with rough, bark-like skin, while sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) are sweeter, moister vegetables with thin skin commonly sold as “yams” in North America. The confusion stems from historical marketing practices in the US—not botanical similarity.

Ever stood in the grocery store wondering why some sweet potatoes are labeled “yams” while others aren't? You're not alone. Despite common belief, yams and sweet potatoes are entirely different vegetables with distinct origins, characteristics, and culinary properties. This confusion affects millions of shoppers annually, leading to recipe failures and nutritional misunderstandings. Let's clarify this once and for all with scientifically verified information you can trust.

Botanical Basics: Why They're Not the Same Plant

True yams belong to the Dioscorea genus with over 600 varieties, primarily cultivated in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. These tubers grow extremely large—some exceeding 100 pounds—and contain significantly less sugar than sweet potatoes. Their scientific classification places them in the Dioscoreaceae family, completely separate from sweet potatoes.

Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas), meanwhile, are members of the morning glory family (Convolvulaceae). Native to Central and South America, they've been cultivated for over 5,000 years. Despite their name, they're not related to regular potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) either. The key distinction: sweet potatoes develop from the root system, while true yams are stem tubers.

Historical Mix-Up: How Sweet Potatoes Became “Yams” in America

The mislabeling originated in the early 20th century when orange-fleshed sweet potatoes were introduced to distinguish them from traditional white-fleshed varieties. According to the USDA Agricultural Research Service, Southern producers began calling orange sweet potatoes “yams” to differentiate them from other varieties, borrowing the African word „nyami” for starchy vegetables. This marketing tactic stuck, creating decades of confusion.

| Characteristic | True Yam | Sweet Potato (Labeled as “Yam”) |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Family | Dioscoreaceae | Convolvulaceae |

| Skin Texture | Rough, bark-like, difficult to peel | Thin, smooth, easily peeled |

| Flesh Color | White, purple, or reddish | Orange, white, or purple |

| Moisture Content | Dry, starchy | Moist, sweet |

| Availability in US | Rare (specialty markets) | Widely available |

How to Identify Them in Your Grocery Store

When shopping in North America, what's labeled “yam” is almost certainly a sweet potato. True yams are uncommon outside African or Caribbean specialty markets. Look for these visual cues:

- Skin appearance: True yams have thick, scaly skin resembling tree bark, while sweet potatoes have smoother, thinner skin

- Shape: Yams tend to be cylindrical with black skin; sweet potatoes are tapered with copper-colored skin

- Flesh color: Orange flesh always indicates sweet potato—true yams rarely have orange flesh

The USDA actually requires that any product labeled “yam” in the US must also include “sweet potato” in the description, though enforcement is inconsistent.

Nutritional Differences You Should Know

While both provide valuable nutrients, their nutritional profiles differ significantly. According to research from USDA FoodData Central, a medium sweet potato (130g) contains approximately 103 calories, 24g carbohydrates, and 438% of your daily vitamin A needs. True yams, by comparison, contain more potassium and resistant starch but less vitamin A.

The orange color in sweet potatoes comes from beta-carotene, which converts to vitamin A in your body. This explains why sweet potatoes are sometimes called “vitamin A potatoes.” True yams lack this pigment, resulting in white or purple flesh with different nutritional benefits.

Cooking Implications: Why the Difference Matters

Understanding this distinction affects your cooking results. Sweet potatoes caramelize beautifully when roasted due to their sugar content, making them ideal for dishes like candied yams or sweet potato pie. True yams, being starchier and drier, behave more like regular potatoes—better suited for boiling or frying in savory dishes.

Professional chefs like Maya Gonzalez note: “In Caribbean cooking, substituting sweet potatoes for true yams completely changes the texture and flavor profile of traditional dishes like éddo or fufu. The starch content affects how the dish sets and absorbs other flavors.”

Where to Find Authentic Yams

If you're searching for true yams, check African or Caribbean grocery stores, particularly those specializing in West African products. They're often labeled as “nyami,” “genuine yam,” or “African yam.” In the US, they're most commonly available during fall and winter months. Major supermarkets rarely stock true yams—what you see labeled as yams are orange-fleshed sweet potato varieties like Jewel or Garnet.

Common Misconceptions Clarified

Myth: Yams are just a type of sweet potato

Fact: They're from completely different plant families with no botanical relation

Myth: All orange-fleshed varieties are yams

Fact: Orange color indicates beta-carotene-rich sweet potatoes—true yams rarely have orange flesh

Myth: The terms are interchangeable worldwide

Fact: Outside North America, “yam” correctly refers to Dioscorea species, while sweet potatoes have distinct local names

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4