Ever wonder why your restaurant server won't let you take that "leftover" steak home after it's been sitting for hours? The answer lies in understanding TCS foods—a critical food safety concept that protects millions from foodborne illness each year. In this guide, you'll learn exactly what makes a food "TCS," recognize common examples in your kitchen, and implement practical safety measures that could prevent serious health risks.

Understanding TCS Food: The Foundation of Food Safety

TCS stands for Time/Temperature Control for Safety, a classification defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the FDA Food Code. These are foods that require specific time and temperature controls to limit the growth of harmful bacteria or prevent toxin production.

Unlike non-TCS foods (like dry goods or highly acidic items), TCS foods create an ideal environment for pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria when left in the temperature danger zone. The FDA identifies seven characteristics that make foods qualify as TCS:

- High moisture content (water activity above 0.85)

- Near-neutral pH (between 4.6 and 7.5)

- Rich in protein or carbohydrates

- Contains starch

- Natural or added preservatives are insufficient

- Oxygen availability

- Time for microbial growth

Everyday TCS Food Examples You Should Recognize

Many common foods fall under TCS classification, but some might surprise you. Here's a practical reference organized by category:

| Food Category | Common TCS Foods | Non-TCS Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy Products | Milk, cheese (except hard cheeses), yogurt | Aged hard cheeses, butter |

| Meat & Poultry | Raw and cooked beef, poultry, fish, shellfish | Dry-cured meats like salami |

| Eggs | Shell eggs, liquid eggs | Dried egg products |

| Produce | Cut melons, cut leafy greens, cut tomatoes | Whole, intact produce |

| Other | Cooked rice, pasta, sprouts, tofu | Uncooked rice, dried pasta |

Notice how preparation method affects TCS status? That cut watermelon you left on the counter after your picnic has entered TCS territory, while the whole melon sitting on your kitchen counter remains non-TCS. This distinction explains why food safety guidelines change dramatically once you slice, cook, or prepare certain items.

The Science Behind Temperature Danger Zone

Bacteria don't just grow—they multiply exponentially in the danger zone. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pathogenic bacteria can double in number every 20 minutes at room temperature. This means a single bacterium can become over 16 million in just 7 hours.

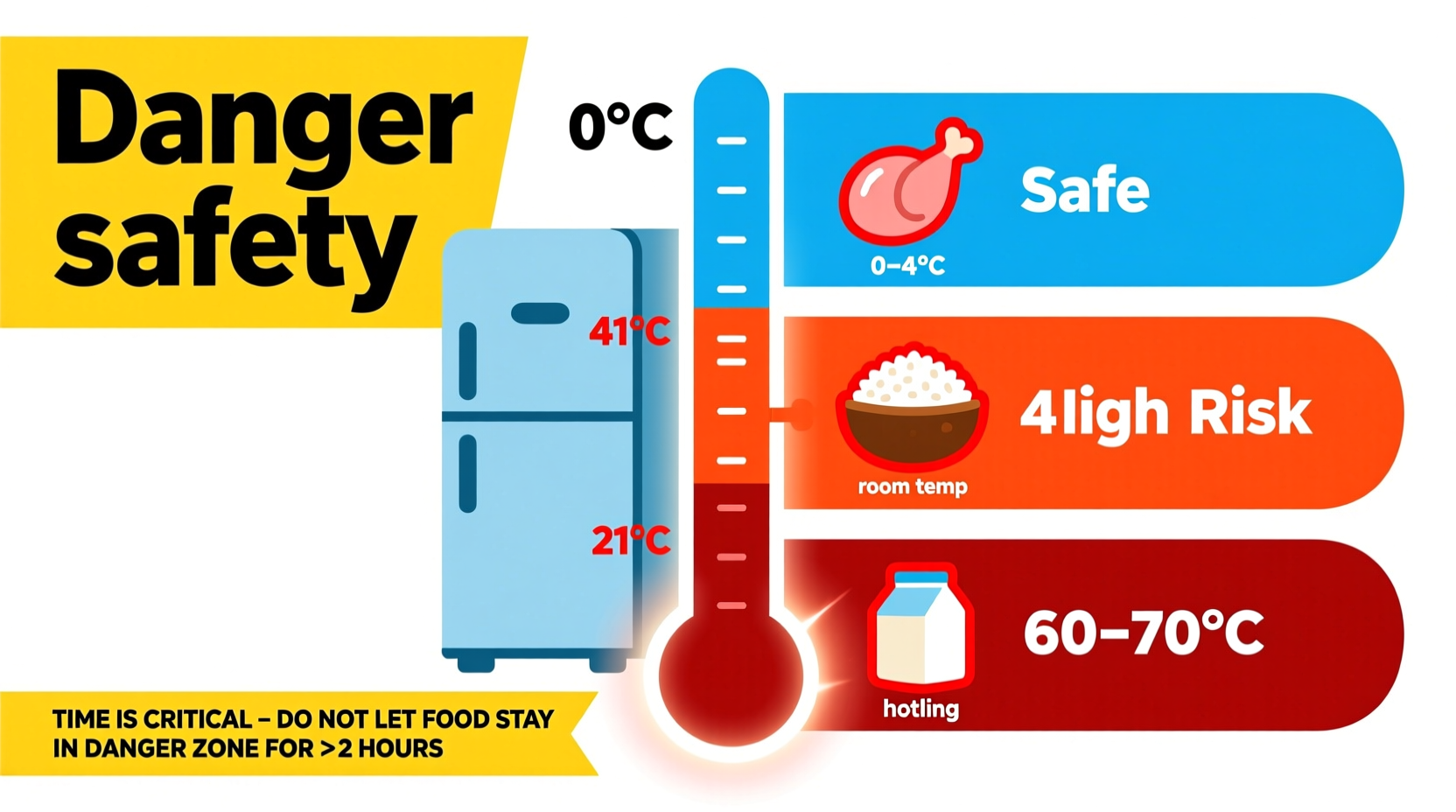

The temperature danger zone spans from 40°F to 140°F (4°C to 60°C), but the most rapid growth occurs between 70°F and 125°F (21°C to 52°C)—exactly the range of most indoor environments. This explains why the "two-hour rule" exists: TCS foods shouldn't remain in the danger zone for more than two hours (or one hour when ambient temperatures exceed 90°F/32°C).

Practical Food Safety Guidelines for TCS Foods

Understanding TCS foods isn't just theoretical—it directly impacts your daily food handling practices. Implement these evidence-based strategies:

Safe Temperature Management

- Refrigeration: Keep TCS foods at 40°F (4°C) or below—use a calibrated thermometer to verify

- Cooking: Reach minimum internal temperatures (165°F/74°C for poultry, 145°F/63°C for fish)

- Cooling: Reduce food from 135°F to 70°F within 2 hours, then to 41°F within additional 4 hours

- Hot holding: Maintain at 135°F (57°C) or above for service

Common Handling Mistakes to Avoid

- Thawing food at room temperature (use refrigerator, cold water, or microwave)

- Cross-contamination between raw and ready-to-eat TCS foods

- Using the same cutting board for multiple TCS food categories without proper sanitation

- Assuming "fresh" or "organic" means safer (these attributes don't affect TCS status)

Special Considerations for Different Settings

While TCS principles remain consistent, application varies by context. The USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service notes significant differences between commercial and home food handling:

- Home kitchens: Focus on proper refrigeration, avoiding the two-hour rule violations, and using food thermometers

- Commercial kitchens: Require detailed time-temperature logs, specific cooling procedures, and certified food protection managers

- Outdoor events: Use insulated containers with ice packs; monitor food with thermometers rather than time estimates

- Leftovers: Divide large portions into shallow containers for rapid cooling before refrigeration

Remember that certain circumstances alter TCS requirements. For example, properly acidified tomatoes (pH below 4.6) or reduced-moisture foods may no longer qualify as TCS. Always verify with current FDA Food Code guidelines when modifying recipes or preparation methods.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4