Understanding the critical distinction between food intoxication and food poisoning could protect you from severe illness. While both fall under foodborne illnesses, their mechanisms differ significantly, affecting prevention strategies and treatment approaches. This guide delivers medically accurate information from CDC and FDA sources to help you recognize risks, implement effective prevention measures, and respond appropriately when exposure occurs.

Food Intoxication vs. Food Poisoning: Clearing the Confusion

Many people use "food poisoning" as a catch-all term, but food intoxication represents a specific mechanism of foodborne illness. The critical difference lies in when and where the harmful substances are produced.

| Characteristic | Food Intoxication | Food Poisoning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Pre-formed toxins in food | Live pathogens multiplying in body |

| Onset Time | 30 minutes to 6 hours | 6 hours to several days |

| Common Pathogens | Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus | Salmonella, E. coli, Norovirus |

| Heat Resistance | Toxins often heat-stable | Pathogens usually killed by cooking |

| Prevention Focus | Temperature control during storage | Proper cooking temperatures |

This distinction matters because reheating contaminated food won't eliminate intoxication risks—Staphylococcus aureus toxins remain dangerous even after boiling. Recognizing this helps explain why properly cooked leftovers can still make you sick if they've been sitting at room temperature too long.

The Science Behind Food Intoxication: How Toxins Take Hold

Food intoxication happens when bacteria multiply in food under favorable conditions (typically the "danger zone" between 40°F and 140°F/4°C and 60°C), producing toxins before consumption. Unlike infections where pathogens invade your system, these pre-formed toxins immediately affect your gastrointestinal tract upon ingestion.

Staphylococcus aureus represents the most common cause, responsible for approximately 200,000 annual cases in the United States according to CDC data. This bacteria thrives in foods handled frequently with bare hands—sandwich meats, salads, and pastries—producing heat-stable enterotoxins that survive cooking.

Bacillus cereus causes "fried rice syndrome" when cooked rice sits at room temperature, allowing spores to germinate and produce emetic toxins. The FDA Food Code identifies cooked rice, pasta, and sauces as particularly vulnerable to this pathogen.

Symptom Timeline: What to Expect After Exposure

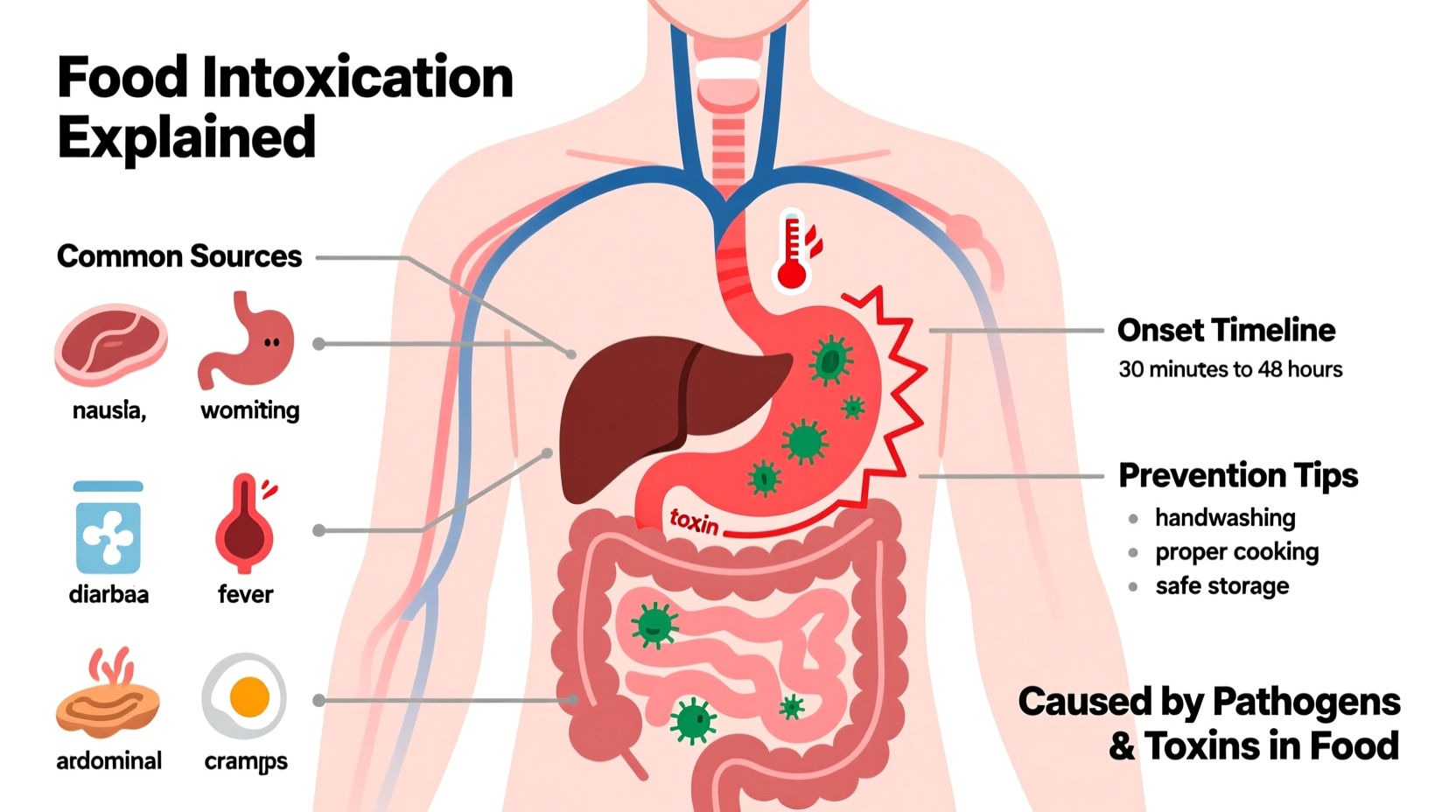

Food intoxication follows a predictable pattern that helps distinguish it from other foodborne illnesses:

- 0-30 minutes: Initial nausea and stomach discomfort (in severe cases)

- 30 minutes-6 hours: Peak symptom development including violent vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea

- 6-24 hours: Symptoms typically subside as toxins pass through your system

- 24+ hours: Full recovery for most healthy adults; prolonged symptoms indicate possible complication

This rapid onset differentiates intoxication from infections like Salmonella, which usually take 6-72 hours to manifest. The short duration—typically resolving within 24 hours—occurs because your body eliminates pre-formed toxins rather than fighting an active infection.

Vulnerable Populations: When Food Intoxication Becomes Dangerous

While most healthy adults recover from food intoxication without complications, certain groups face heightened risks:

- Infants and children under 5 (immature digestive systems)

- Adults over 65 (reduced stomach acid production)

- Immunocompromised individuals (cancer patients, organ transplant recipients)

- Pregnant women (altered immune response)

For these vulnerable populations, even mild cases can lead to severe dehydration requiring medical intervention. The CDC reports hospitalization rates for foodborne illnesses are five times higher among adults over 65 compared to younger adults. Dehydration becomes particularly dangerous when vomiting prevents fluid retention—seek medical help if you can't keep liquids down for 12 hours.

Prevention Protocol: Your 5-Step Defense System

Since you can't detect toxin-contaminated food by sight, smell, or taste, prevention requires strict temperature control. Implement these evidence-based strategies from the FDA Food Code:

- Master the Danger Zone: Keep cold foods below 40°F (4°C) and hot foods above 140°F (60°C). Use appliance thermometers to verify temperatures.

- Time is Critical: Discard perishable foods left at room temperature more than 2 hours (1 hour if above 90°F/32°C).

- Cool Smartly: Divide large leftovers into shallow containers for rapid cooling. Never leave a whole pot of soup to cool on the counter.

- Hand Hygiene Matters: Wash hands thoroughly before handling food, especially after touching your face or hair—critical for preventing Staph transmission.

- Reheat Properly: While reheating won't destroy existing toxins, it kills additional bacteria. Heat leftovers to 165°F (74°C) throughout.

Particularly high-risk foods requiring extra caution include:

- Cooked rice and pasta dishes (Bacillus cereus risk)

- Cold salads with mayonnaise (despite common myths, the risk comes from temperature abuse, not the mayo itself)

- Deli meats and sliced cheeses

- Cream-filled pastries and sandwiches

When to Seek Medical Attention: Recognizing Danger Signs

Most food intoxication cases resolve with rest and hydration, but watch for these red flags requiring immediate medical care:

- Signs of severe dehydration (dark urine, dizziness, rapid heartbeat)

- Blood in vomit or stool

- Symptoms lasting longer than 24 hours

- High fever (above 101.5°F/38.6°C)

- Neurological symptoms like blurred vision or muscle weakness

If you suspect food intoxication, document everything you ate in the previous 24 hours. This information helps healthcare providers identify potential sources and determine if public health authorities need notification. The CDC recommends saving suspicious food samples in sealed containers for possible testing.

Common Questions About Food Intoxication

Can you get food intoxication from properly cooked food?

Yes, cooking kills bacteria but doesn't destroy pre-formed toxins. Foods like rice or meats cooked properly but left at room temperature for too long can still cause intoxication from heat-stable toxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus.

How quickly do symptoms of food intoxication appear?

Symptoms typically develop rapidly, usually within 30 minutes to 6 hours after consuming contaminated food. This quick onset distinguishes intoxication from foodborne infections, which often take 6-72 hours to manifest.

Is food intoxication contagious?

No, food intoxication itself isn't contagious since it's caused by pre-formed toxins, not live pathogens. However, if the contaminated food also contains infectious agents (like norovirus), those could potentially spread to others through poor hygiene practices.

What's the difference between food intoxication and food infection?

Food intoxication occurs when you consume pre-formed toxins in food, causing rapid symptoms. Food infection happens when live pathogens multiply in your digestive system after ingestion, with delayed symptom onset. Intoxication involves toxins produced before consumption; infection involves pathogens growing inside your body.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4