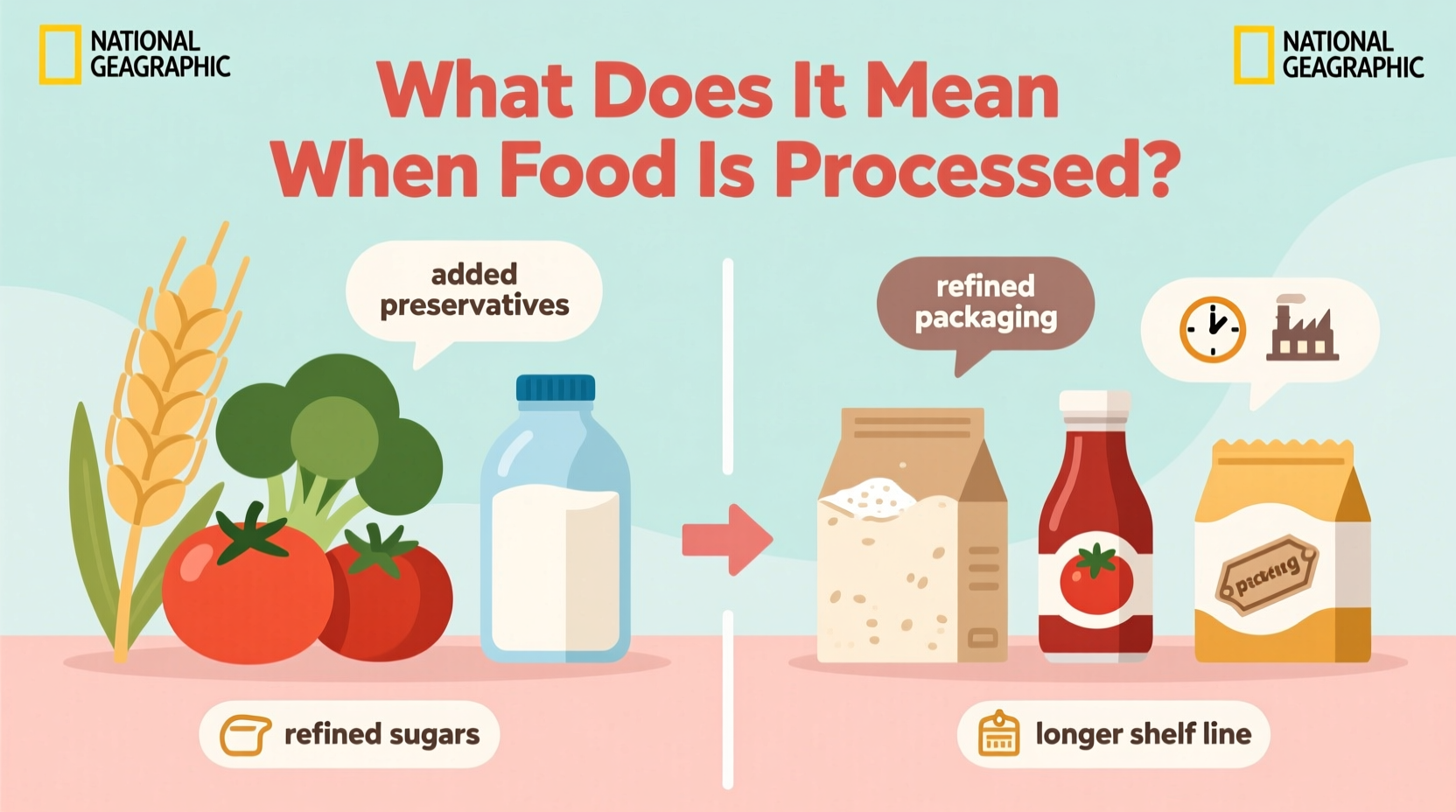

Ever wonder why your grocery store offers both fresh apples and apple sauce? The answer lies in food processing—a spectrum of techniques humans have used for millennia to make food safer, tastier, and more accessible. Understanding what processed food truly means empowers you to make informed choices without unnecessary fear.

Breaking Down Food Processing: It's Not What You Think

Food processing simply refers to any method that alters raw agricultural products into forms suitable for consumption, storage, or distribution. From the moment you wash berries before eating them to the industrial production of ready-to-eat meals, processing exists on a continuum.

"The term 'processed food' carries negative connotations today, but processing itself isn't inherently bad," explains Antonio Rodriguez, culinary expert with extensive knowledge of food chemistry. "Humans have processed food since discovering fire. The key is understanding how and why foods are processed."

The Processing Spectrum: From Farm to Fork

Processed foods exist along a spectrum from minimal to extensive intervention. Recognizing where foods fall on this continuum helps you make smarter choices:

| Processing Level | Common Techniques | Everyday Examples | Nutritional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Processing | Washing, cutting, freezing, pasteurizing | Bagged spinach, frozen berries, roasted nuts | Preserves most nutrients; may enhance availability |

| Moderate Processing | Cooking, fermenting, canning, fortifying | Canned tomatoes, yogurt, whole-grain bread | May reduce some nutrients but increases others; adds convenience |

| Heavy/Ultra-Processing | Extrusion, hydrogenation, multiple additives | Soda, packaged snacks, instant noodles | Often high in sugar/salt/fat; low in fiber; may contain artificial additives |

Why Food Gets Processed: More Than Just Convenience

Processing serves several legitimate purposes that benefit both consumers and food systems:

- Safety: Pasteurization kills harmful bacteria in milk and juice

- Preservation: Canning and freezing extend shelf life significantly

- Nutritional Enhancement: Fortification adds vitamins to staple foods (e.g., folic acid in flour)

- Accessibility: Processing makes seasonal foods available year-round

- Waste Reduction: Transforming imperfect produce into soups or sauces

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, many processing techniques actually improve food safety and nutritional value compared to raw forms.

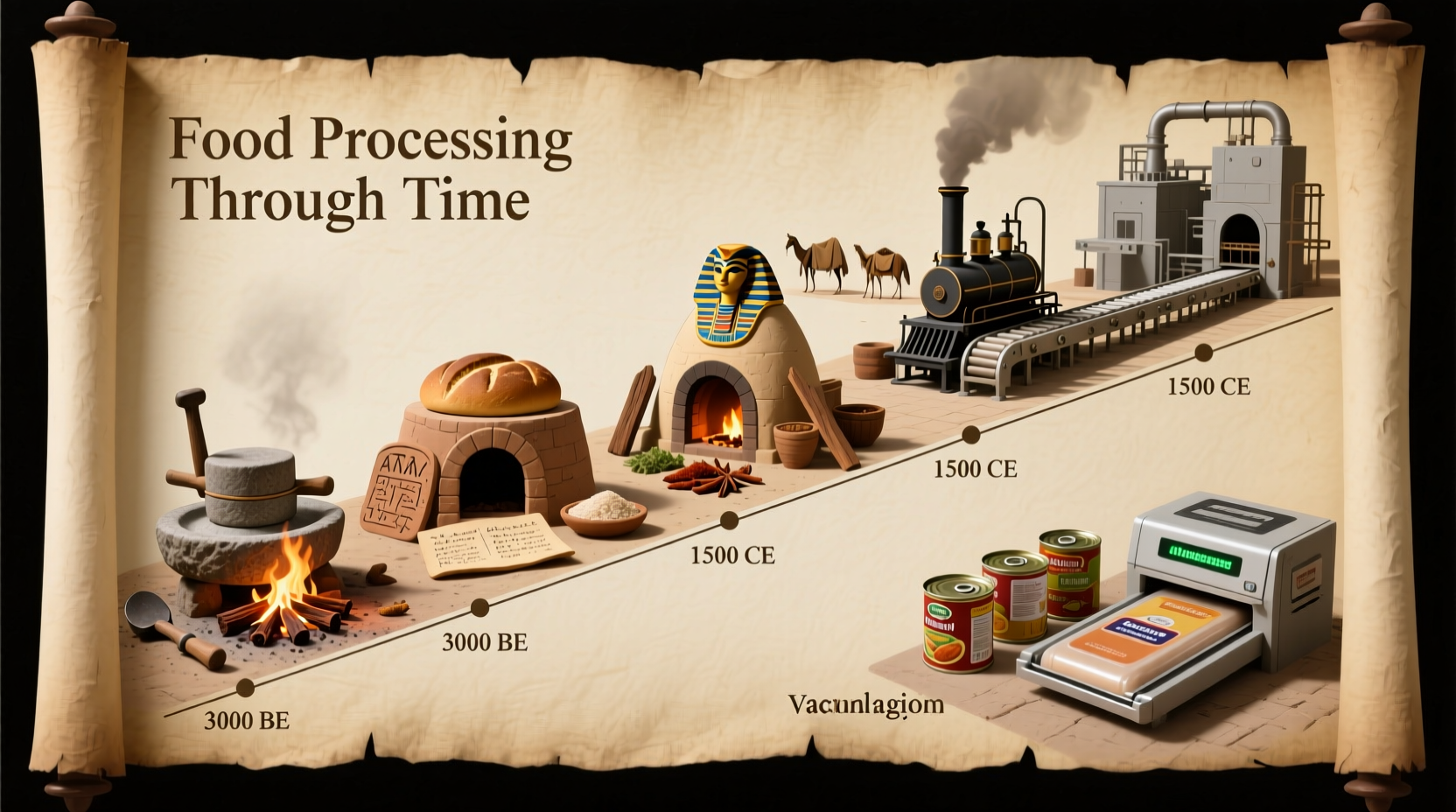

Food Processing Through Time: An Evolutionary Timeline

Understanding the historical context of food processing reveals how these techniques evolved from necessity to sophisticated science:

- Prehistoric Era: Early humans discovered fire, enabling cooking—the original food processing technique that made nutrients more accessible

- Ancient Civilizations: Fermentation for bread and beer, sun-drying for preservation

- 1800s: Invention of canning preserves food for long voyages and military use

- Early 1900s: Pasteurization becomes standard for dairy safety

- Mid-1900s: Freezing technology advances, creating frozen dinners and vegetables

- 1970s-Present: Rise of ultra-processed foods with sophisticated ingredient systems

This historical progression shows how food processing responded to genuine human needs—safety concerns, seasonal limitations, and growing populations—rather than being merely a modern convenience.

Reading Between the Lines: Understanding Food Labels

When evaluating processed foods, focus on these practical indicators rather than fearing the term "processed" itself:

- Ingredient List Length: Shorter lists typically indicate less processing

- Recognizable Ingredients: Can you identify and pronounce most components?

- Additive Purpose: Preservatives like vitamin C (ascorbic acid) serve useful functions

- Nutrition Facts: Compare sodium, added sugars, and fiber content to similar products

"Don't automatically reject foods with additives," advises Rodriguez. "Some preservatives actually prevent spoilage and foodborne illness. The question should be why the additive is there and whether the benefits outweigh potential concerns."

Making Smarter Choices: A Practical Framework

Instead of labeling all processed foods as "bad," use this practical approach when shopping:

- Identify the processing level: Is it minimally processed (like pre-cut vegetables) or ultra-processed (like candy bars)?

- Check the ingredient purpose: Does added salt serve as preservative or just for flavor?

- Consider nutritional value: Does the product offer meaningful nutrients per serving?

- Evaluate frequency: Is this something you'd eat daily or occasionally?

Research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health suggests focusing on overall dietary patterns rather than eliminating all processed foods. Their studies show that diets rich in whole foods with strategic inclusion of minimally processed items provide the best balance of nutrition, safety, and enjoyment.

Common Misconceptions About Processed Foods

Several myths persist about processed foods that deserve clarification:

- Myth: All processed foods contain harmful chemicals

Reality: Many processing techniques use natural methods; even "natural" foods contain chemical compounds - Myth: Processed means less nutritious

Reality: Some processing increases nutrient availability (like lycopene in cooked tomatoes) - Myth: Fresh is always better than frozen or canned

Reality: Frozen produce often retains more nutrients than "fresh" items that traveled long distances

The World Health Organization acknowledges that processing plays a crucial role in food security, particularly in regions with limited access to fresh produce year-round. Their healthy diet guidelines emphasize balance and variety rather than complete avoidance of processed items.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4