Understanding what human flesh might taste like involves complex biological, ethical, and historical considerations. This article provides scientifically accurate information about human taste perception while addressing common misconceptions. You'll learn why the question itself reflects a misunderstanding of sensory biology, discover the actual science behind taste receptors, and explore documented historical contexts without sensationalism.

The Biological Reality of Taste Perception

Taste isn't an inherent property of substances but rather a neurological response created when chemical compounds interact with our taste receptors. As Dr. Linda Bartoshuk, a leading taste researcher at the University of Florida explains, "We don't taste food—we taste the molecules that food releases when we eat it." Human tissue doesn't release flavor compounds in the same way that food items do because we're not designed to consume other humans.

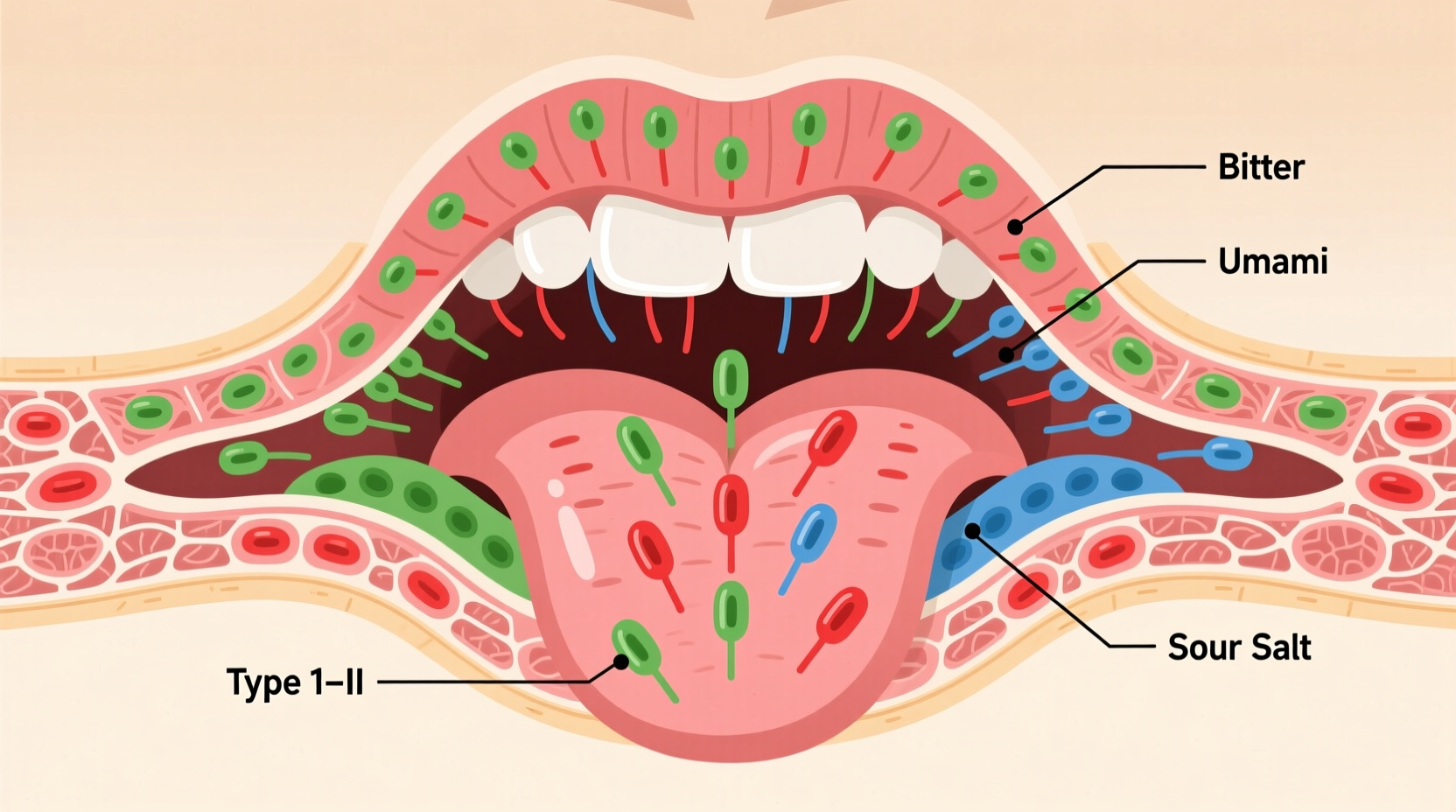

Our five basic taste receptors detect:

- Sweet (carbohydrates)

- Salty (sodium ions)

- Sour (acids)

- Bitter (potential toxins)

- Umami (amino acids like glutamate)

When anthropologists study historical dietary practices, they focus on nutritional composition rather than subjective taste experiences. According to research published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, human muscle tissue composition most closely resembles that of omnivorous primates like chimpanzees, with protein profiles similar to pork but with significant biological differences that affect potential sensory experience.

| Biological Component | Human Tissue | Common Meat Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Composition | Unique human-specific proteins | Pork (closest structural match) |

| Fat Content | Higher unsaturated fats | Beef (higher saturated fats) |

| Myoglobin Levels | Lower concentration | Beef (high concentration) |

| Unique Risks | Prion diseases (kuru, CJD) | None from standard meats |

Historical Context Without Sensationalism

Anthropological records document rare instances of ritualistic cannibalism in specific historical contexts, but these accounts focus on cultural practices rather than sensory descriptions. The Smithsonian Institution's Department of Anthropology maintains that "no credible scientific documentation exists describing the taste of human flesh, as ethical research standards prohibit such investigation."

Documented Historical Context Timeline

- Prehistoric Era: Limited evidence of nutritional cannibalism during extreme scarcity

- 16th-19th Century: European explorers documented ritual practices (often with cultural bias)

- 1950s: Scientific study of kuru epidemic among Fore people of Papua New Guinea

- 1970s-Present: Strict ethical guidelines prohibit any research involving human tissue consumption

Why This Question Misunderstands Sensory Biology

The question "what does human taste like" reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how taste works. Taste scientists emphasize that:

- Taste is created by our neurological response, not inherent in the substance

- Our aversion to consuming human tissue is biologically programmed

- No controlled scientific study has ever documented human flesh as food

The National Institutes of Health states that "prion diseases like kuru, which affected the Fore people of Papua New Guinea through ritualistic endocannibalism, demonstrate why human tissue consumption poses unique biological risks not present with other meats." These diseases have incubation periods of up to 50 years and are always fatal.

Scientific Alternatives for Culinary Curiosity

If you're interested in human sensory biology or historical food practices, consider these scientifically valid avenues of exploration:

- Study the evolution of human taste receptors through resources from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists

- Explore how cultural taboos develop around food through documented anthropological research

- Investigate the biochemistry of meat alternatives that mimic various protein structures

- Learn about historical food preservation techniques that shaped human dietary evolution

Ethical and Legal Boundaries

It's crucial to understand that human tissue consumption is:

- Illegal in every country under murder, desecration, and public health laws

- Ethically prohibited by all major medical and anthropological associations

- Biologically dangerous due to unique disease transmission risks

- Considered a severe violation of human rights by international standards

The World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki explicitly prohibits any research involving human tissue consumption, stating such practices violate fundamental ethical principles of medical research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there any scientific documentation of human flesh taste?

No credible scientific documentation exists. Ethical research standards prohibit such investigation, and historical accounts often contain cultural biases or sensationalism rather than objective descriptions.

Why is human flesh consumption particularly dangerous?

Human tissue consumption poses unique risks of prion diseases like kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which have long incubation periods and are always fatal. These diseases transmit efficiently between humans but not between species.

How do taste receptors actually work?

Taste receptors detect chemical compounds released when we eat. Five basic receptors identify sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami compounds. The brain combines these signals with smell and texture to create flavor perception—it's a neurological experience, not an inherent property of food.

Are there legal alternatives to explore unusual tastes?

Yes, many culinary institutions offer courses on global food traditions, molecular gastronomy, and historical cooking techniques. The American Anthropological Association also provides resources on cultural food practices that satisfy curiosity within ethical boundaries.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4