Discover exactly what causes tomato blight and how to protect your garden. This guide explains the specific pathogens responsible, the environmental triggers that activate them, and practical prevention strategies based on agricultural science—so you can diagnose problems accurately and save your tomato plants before it's too late.

Understanding the Two Main Blight Pathogens

When gardeners ask what causes tomato blight, they're usually encountering one of two distinct diseases with different origins. Identifying which pathogen is affecting your plants determines your treatment approach. Let's examine both culprits.

Early Blight: The Persistent Fungal Invader

Early blight stems from Alternaria solani, a resilient fungus that survives winters in infected plant debris and soil. This pathogen doesn't require perfect conditions to thrive—it can infect tomatoes at temperatures between 68-86°F (20-30°C) with just 8-12 hours of continuous leaf moisture.

What causes early blight to explode in your garden? Three key factors:

- Infected plant residue left in soil from previous seasons

- Overhead watering that keeps leaves wet for extended periods

- Plant stress from nutrient deficiencies or physical damage

Unlike its more dramatic cousin, early blight typically appears after fruiting begins, starting with those distinctive bullseye-patterned spots on older leaves. The University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources confirms that early blight spores spread through rain splash and wind, making crowded plantings particularly vulnerable.

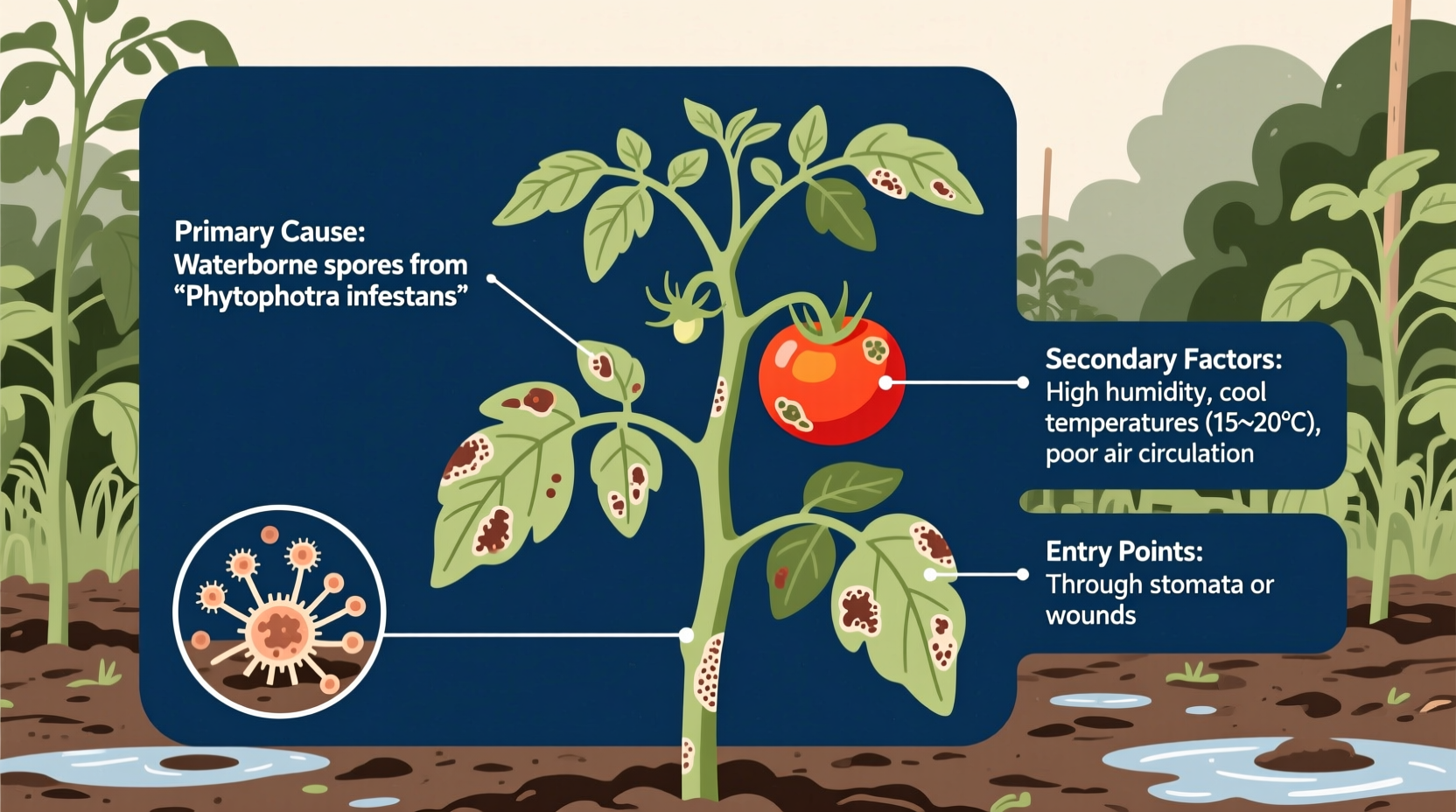

Late Blight: The Rapid Destroyer

When people ask what causes tomato blight that wipes out entire plants overnight, they're usually describing late blight from Phytophthora infestans. This aggressive pathogen famously triggered the Irish Potato Famine and remains agriculture's nightmare.

Late blight requires specific conditions to activate:

- Temperatures between 60-78°F (15-25°C)

- High humidity (90%+) or continuous leaf wetness for 6+ hours

- Presence of infected potato plants or volunteer tomatoes

Unlike early blight, late blight can strike at any growth stage. The USDA Agricultural Research Service documents how late blight spreads through airborne spores that travel miles in favorable conditions. This explains why your plants might suddenly develop water-soaked lesions overnight following a cool, rainy period.

| Characteristic | Early Blight | Late Blight |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Pathogen | Alternaria solani | Phytophthora infestans |

| Temperature Range | 68-86°F (20-30°C) | 60-78°F (15-25°C) |

| Moisture Requirement | 8-12 hours leaf wetness | 6+ hours continuous moisture |

| Initial Symptoms | Bullseye spots on older leaves | Water-soaked lesions on any foliage |

| Progression Speed | Gradual (weeks) | Rapid (days) |

Environmental Triggers That Activate Blight

Understanding what causes tomato blight means recognizing how environmental factors transform dormant pathogens into active threats. Cornell University's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences identifies three critical weather patterns that trigger outbreaks:

Extended Leaf Wetness: The Critical Catalyst

Whether from rain, dew, or improper watering, prolonged moisture on leaves creates the perfect infection court. Research shows that Alternaria solani requires 8+ hours of leaf wetness to germinate, while Phytophthora infestans needs just 6 hours. This explains why drip irrigation significantly reduces blight incidence compared to overhead watering.

Temperature Windows for Infection

Each pathogen has specific temperature preferences that determine when what causes tomato blight becomes an immediate threat:

- Early blight thrives in warm conditions (75-85°F/24-29°C)

- Late blight prefers cooler temperatures (60-70°F/15-21°C)

Monitoring your garden's microclimate with a simple thermometer helps predict infection windows. The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map provides baseline temperature data for your region that correlates with blight risk periods.

Humidity's Hidden Role

High relative humidity (above 85%) allows spores to remain viable longer and increases leaf wetness duration. In humid climates, even brief rain showers can trigger outbreaks because the air doesn't dry plants quickly. This explains why coastal gardeners often battle blight more severely than those in arid regions.

Cultural Practices That Invite Blight

While pathogens cause tomato blight, certain gardening practices create ideal conditions for infection. Identifying these factors helps answer what causes tomato blight in my garden specifically.

Planting Density Matters More Than You Think

Crowded plantings reduce air circulation, extending leaf wetness periods. University extension studies show that spacing tomatoes 24-36 inches apart reduces early blight incidence by 40% compared to traditional 18-inch spacing. Proper spacing isn't just about plant size—it's a critical moisture management strategy.

The Soil Connection

Infected soil serves as a reservoir for Alternaria solani. Crop rotation with non-solanaceous plants (like beans or brassicas) for 2-3 years breaks the disease cycle. The Cornell Vegetable Program confirms that rotating out of tomatoes for three years reduces early blight pressure by 70%.

Watering Techniques That Make or Break Your Plants

When gardeners ask what causes tomato blight after I water, the answer often lies in their irrigation method. Overhead watering splashes soil-borne spores onto leaves, while drip irrigation keeps foliage dry. Watering in the morning allows plants to dry before evening humidity rises—critical for preventing late blight.

Prevention Strategies Based on Cause

Effective prevention targets the specific causes of each blight type. Implement these science-backed methods:

For Early Blight Prevention

- Remove lower leaves touching soil to prevent splash transmission

- Apply mulch immediately after planting to block soil spores

- Use copper-based fungicides preventatively during wet periods

For Late Blight Defense

- Monitor local late blight reports through the USABlight monitoring system

- Apply protective fungicides before forecasted rain events

- Remove volunteer potato/tomato plants that harbor the pathogen

When to Suspect Blight vs. Other Issues

Not all leaf spotting indicates blight. Confirm what causes tomato blight-like symptoms by checking for these distinctive signs:

- Early blight: Concentric rings in lesions with yellow halo

- Late blight: Greasy-looking spots with white fungal growth underneath in high humidity

- Not blight: Uniform yellowing (nutrient deficiency) or circular spots with purple borders (Septoria)

When in doubt, submit samples to your local cooperative extension service for laboratory diagnosis. Misidentifying what causes tomato blight leads to ineffective treatments that waste time and resources.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4