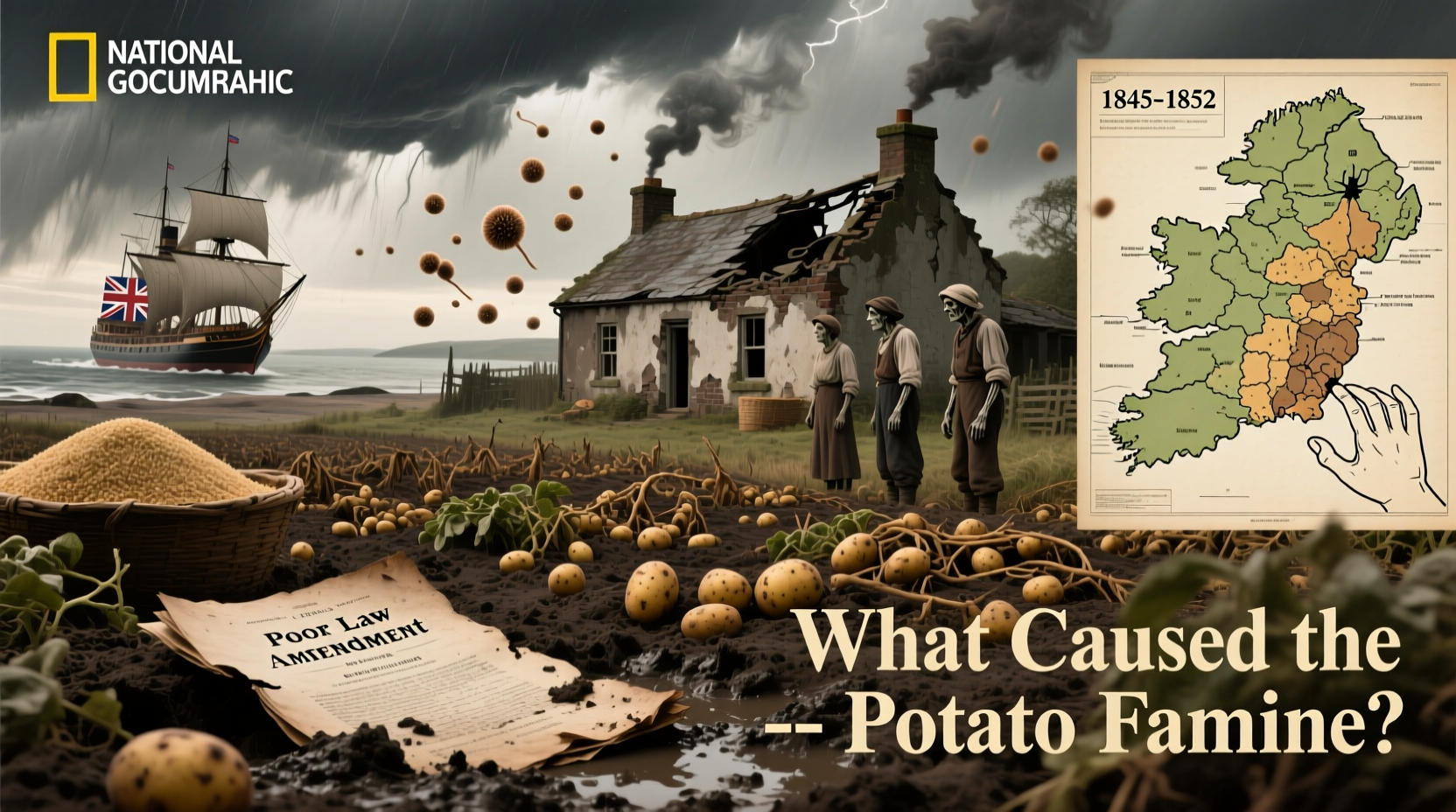

For millions of Irish citizens in the mid-19th century, the sudden failure of their primary food source wasn't just an agricultural disaster—it triggered a humanitarian crisis that reshaped Ireland's population and history forever. Understanding what caused the potato famine requires examining both the biological catastrophe and the complex social conditions that turned crop failure into mass starvation.

The Immediate Biological Trigger: Late Blight Disease

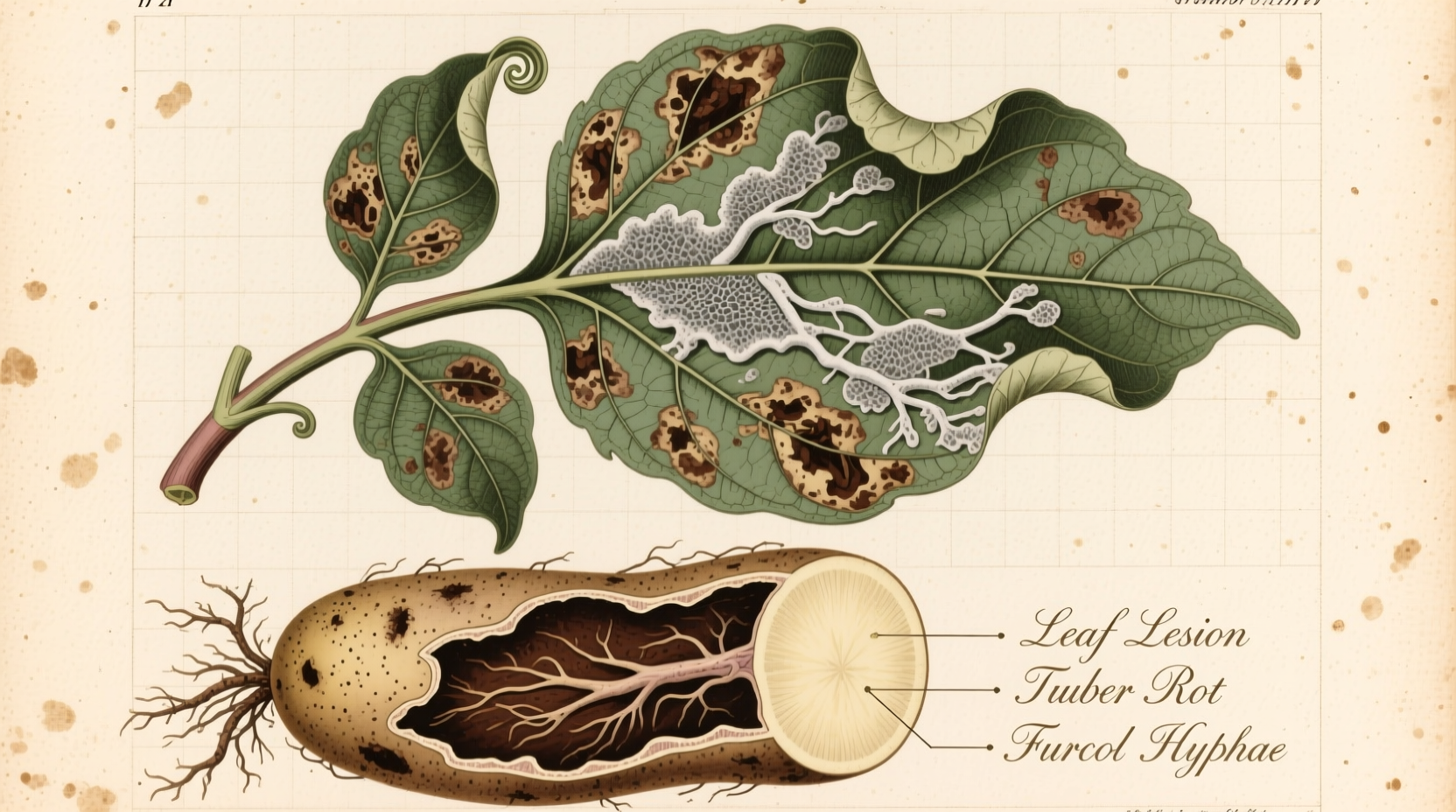

At the heart of the famine was Phytophthora infestans, a water mold that causes late blight in potatoes. This pathogen likely originated in South America and arrived in Europe in 1845, reaching Ireland by summer of that year. Unlike typical plant diseases, late blight spreads rapidly in cool, wet conditions—exactly the Irish climate during the critical growing season.

When infected, potato plants developed dark lesions on leaves that quickly turned black and mushy. Within days, the entire plant would collapse, and the tubers would rot in the ground. The 1845 harvest saw approximately one-third of Ireland's potato crop destroyed. By 1846, the situation worsened dramatically as nearly the entire crop failed.

| Year | Percentage Crop Loss | Key Events |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | ~33% | First appearance of late blight; partial failure |

| 1846 | ~75% | Catastrophic failure; widespread starvation begins |

| 1847 | ~70% | "Black '47"—worst year; peak mortality |

| 1848-1849 | ~40-50% | Recurring outbreaks; continued hardship |

Why Crop Failure Became Famine: Ireland's Vulnerable Food System

The critical question isn't just what caused the potato blight, but why this agricultural disaster became a human catastrophe. Three interconnected factors created Ireland's extreme vulnerability:

Complete Dependence on a Single Crop

By the 1840s, approximately 8 million Irish people relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance. For the rural poor, potatoes provided up to 90% of daily calories. A single acre of potatoes could feed a family of six, making it the perfect crop for tenant farmers working small plots on absentee landlords' estates. When the blight hit, there was no dietary fallback for millions.

Colonial Economic Structures

Despite the famine, Ireland remained a net exporter of food during the crisis. Historical records from the Irish National Archives show that in 1847 alone, Ireland exported 4,000 vessels of grain to England while its population starved. British economic policies required Irish tenant farmers to pay rent in cash, forcing them to sell other crops rather than consume them.

Inadequate Government Response

The British government's response was shaped by prevailing economic theories of the time. Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel initially purchased maize from America, but his successor Lord John Russell terminated direct food aid in 1846, believing it would disrupt free markets. Public works programs required increasingly difficult labor for diminishing food rations, and the Poor Law system became overwhelmed as death rates soared.

Human Impact: Death, Disease, and Displacement

The consequences of what caused the potato famine extended far beyond hunger:

- Death toll: Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases like typhus and cholera between 1845-1852

- Emigration: Over 1.5 million people fled Ireland, primarily to North America

- Population decline: Ireland's population dropped by 20-25%, a loss from which it has never recovered

- Social disruption: Traditional rural communities disintegrated as evictions increased

Common Misconceptions About the Famine's Causes

Several persistent myths obscure understanding of what caused the potato famine:

"The British deliberately caused the famine"

While British policies worsened the crisis, historical evidence from University College Cork's Great Hunger Institute shows no evidence of intentional genocide. The tragedy resulted from a combination of biological disaster, economic ideology, and administrative failure rather than deliberate malice.

"Potatoes were the only food available"

Ireland produced abundant grain, dairy, and livestock throughout the famine years. The issue wasn't absolute food scarcity but rather economic access—tenant farmers had to sell other crops to pay rent, leaving them unable to purchase available food.

"The famine affected all of Ireland equally"

The crisis hit western and southern regions hardest, where dependence on potatoes was greatest and alternative employment options were limited. Ulster, with its more diversified economy, experienced significantly less severe impacts.

Scientific Understanding of Late Blight Today

Modern research has revealed critical details about Phytophthora infestans that help explain what caused the potato famine. According to studies published in Nature, the 1840s outbreak involved a previously unknown strain called HERB-1 that dominated global potato crops for over 50 years before being replaced by newer strains. This particular variant was exceptionally virulent in the cool, wet Irish climate.

Today's potato varieties have greater genetic diversity and resistance to late blight, but the pathogen remains a serious agricultural threat worldwide, causing approximately $6.7 billion in global losses annually according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Legacy of the Great Hunger

The Irish Potato Famine fundamentally reshaped Ireland's demographic, cultural, and political landscape. Its legacy includes:

- Permanent population decline that continues to affect Ireland today

- Massive Irish diaspora communities in the United States, Canada, and Australia

- Increased land reform movements leading to eventual Irish independence

- Modern agricultural practices emphasizing crop diversity and disease monitoring

Understanding what caused the potato famine reminds us that food security depends not just on agricultural productivity but on equitable economic systems and responsive governance. The lessons of this historical tragedy remain relevant as communities worldwide face climate change and food system vulnerabilities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4