Understanding food starches unlocks better cooking results and smarter nutritional choices. By the end of this article, you'll know exactly how different starches behave in recipes, their nutritional impacts, and which ones work best for specific culinary applications—helping you avoid common kitchen disasters like lumpy sauces or collapsed pastries.

The Science Behind Starch Formation

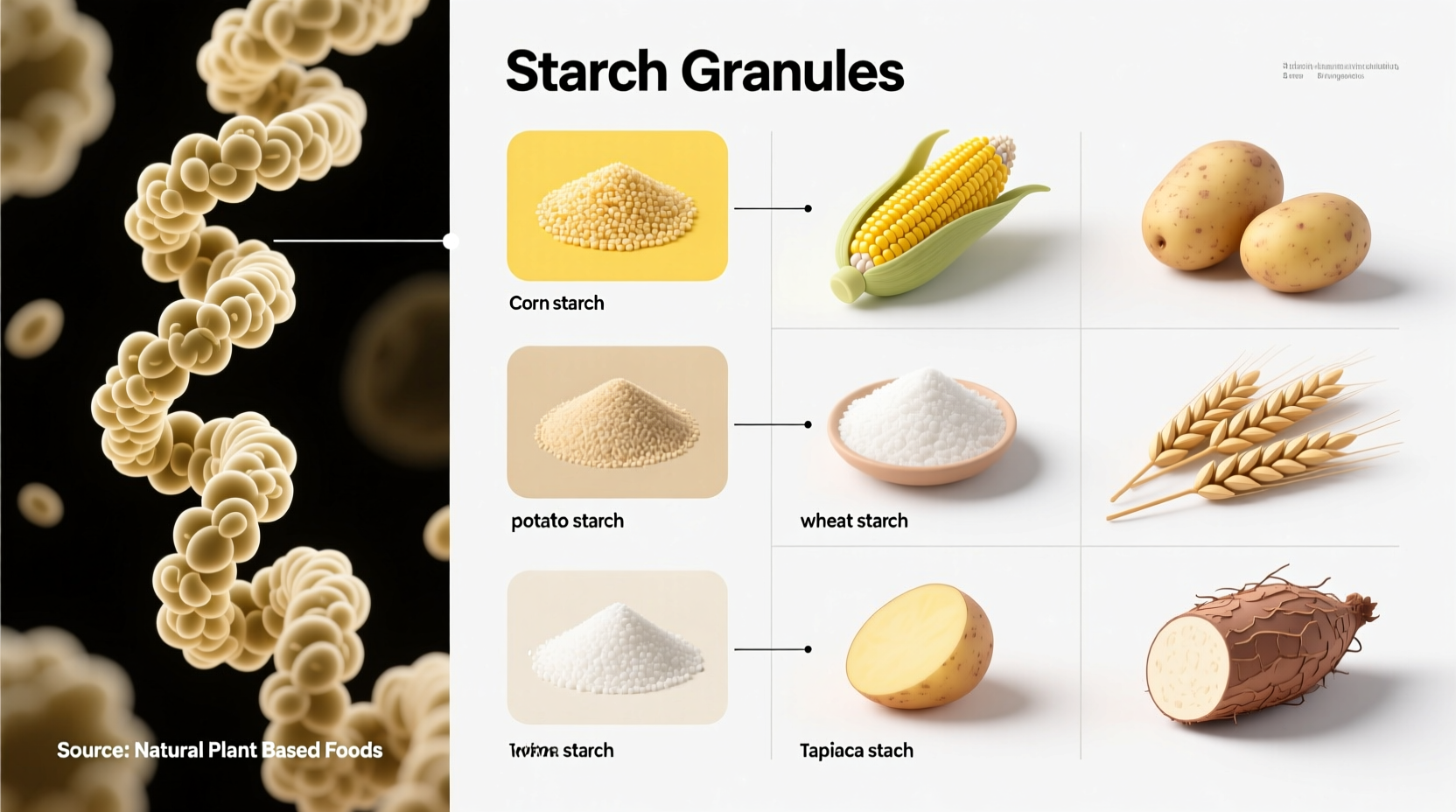

Starches form naturally in plant cells as energy storage molecules. When plants photosynthesize, they convert sunlight into glucose, which then links together into long chains creating two primary components:

- Amylose (20-30%): Straight-chain molecules that create firm gels

- Amylopectin (70-80%): Branched molecules providing viscosity and stability

These microscopic granules remain dormant until they encounter moisture and heat. During cooking, starch granules absorb water, swell up to 30 times their original size, and eventually burst—releasing the thickening power that transforms your favorite recipes. This critical process, known as gelatinization, typically occurs between 140-212°F (60-100°C), depending on the starch source.

Major Food Starches Compared

| Starch Type | Source | Gelatinization Temp | Best Uses | Freeze-Thaw Stable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornstarch | Corn kernels | 144-167°F (62-75°C) | Gravies, fruit pies, stir-fry sauces | Poor |

| Tapioca Starch | Cassava root | 140-158°F (60-70°C) | Doughs, bubble tea, frozen foods | Excellent |

| Potato Starch | Potatoes | 131-149°F (55-65°C) | Clear sauces, gluten-free baking | Good |

| Rice Starch | Rice grains | 149-167°F (65-75°C) | Asian sauces, baby food | Fair |

| Arrowroot | Maranta arundinacea | 140-154°F (60-68°C) | Fruit desserts, delicate sauces | Poor |

This comparison reveals why professional chefs select specific starches for particular applications. For instance, potato starch's low gelatinization temperature makes it ideal for delicate sauces that can't withstand prolonged cooking, while tapioca's freeze-thaw stability makes it the preferred choice for commercially frozen foods. The USDA FoodData Central database confirms these functional differences stem from each starch's unique molecular structure and granule size.

Starch Evolution in Culinary History

Humans have utilized food starches for thousands of years, though our understanding of their science is relatively recent:

- Prehistoric Era: Early humans discovered roasting starchy roots made them more digestible

- Ancient Egypt (3000 BCE): Used wheat starch for adhesive in papyrus production

- Medieval Europe: Chefs employed breadcrumbs as thickeners in sauces

- 1840s: Commercial cornstarch production began in the United States

- 1930s: Food scientists identified the gelatinization process

- Modern Era: Modified food starches engineered for specific industrial applications

This historical progression shows how our relationship with starches evolved from accidental discovery to precise scientific application. According to agricultural research from Cornell University, the development of modified starches has expanded culinary possibilities while maintaining the fundamental thickening properties that made starches valuable since prehistoric times.

Practical Cooking Applications

Mastering starch usage requires understanding these critical techniques:

Creating Perfect Slurries

For smooth results, always mix starch with cold liquid before adding to hot mixtures. The standard ratio is 1 tablespoon starch to 1 cup liquid. Whisk vigorously to eliminate lumps, then slowly pour into your simmering mixture while stirring constantly. Remember that cornstarch requires full boiling to activate, while tapioca works at lower temperatures.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Acidic ingredients like tomatoes or vinegar can break down starch molecules. If thickening acidic foods, add the starch mixture near the end of cooking. Similarly, excessive stirring after gelatinization can shear the starch molecules, causing thinning. For dairy-based sauces, create a roux first to protect the starch from curdling.

Substitution Guidelines

When substituting starches, consider these factors:

- Cornstarch provides more thickening power than flour (use half as much)

- Tapioca creates clearer gels than cornstarch—ideal for fruit fillings

- Potato starch works better in acidic recipes than cornstarch

- Arrowroot loses thickening power when boiled—add at the end

Nutritional Considerations

While starches provide energy (4 calories per gram), their nutritional impact varies significantly:

Resistant starch, found in cooled cooked potatoes and pasta, functions as dietary fiber with proven benefits for gut health. Research published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition shows resistant starch feeds beneficial gut bacteria and may improve insulin sensitivity. However, rapidly digestible starches can cause blood sugar spikes—particularly problematic for individuals with diabetes.

The glycemic index varies considerably between starch sources. For example, potato starch has a GI of 85, while tapioca starch clocks in at 66. Understanding these differences helps home cooks make informed choices, especially when preparing meals for people with specific dietary needs.

When Starch Selection Matters Most

Certain cooking scenarios demand precise starch selection:

- Freeze-thaw applications: Tapioca starch maintains texture after freezing where cornstarch breaks down

- Clear glazes: Arrowroot or tapioca create crystal-clear finishes unlike cloudy cornstarch

- Long-simmered dishes: Potato starch holds up better than cornstarch in extended cooking

- Acidic environments: Modified food starches outperform traditional options in tomato-based sauces

Professional food scientists at the Institute of Food Technologists note that selecting the right starch isn't just about thickening power—it's about matching the starch's molecular behavior to your specific recipe requirements. This context awareness separates adequate results from exceptional ones.

Troubleshooting Guide

Encountering problems with starch-thickened dishes? Try these solutions:

- Lumpy sauce: Strain through fine mesh sieve or use immersion blender

- Thin results: Make additional slurry and whisk in gradually

- Cloudy appearance: Switch to tapioca or arrowroot for clear finishes

- Weeping liquid: Avoid overcooking after thickening—remove from heat promptly

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4