Understanding which foods contain these compounds is essential for managing digestive symptoms effectively. This guide provides scientifically-backed information about FODMAP foods, their impact on gut health, and practical strategies for identifying and managing them in your diet.

Breaking Down the FODMAP Acronym

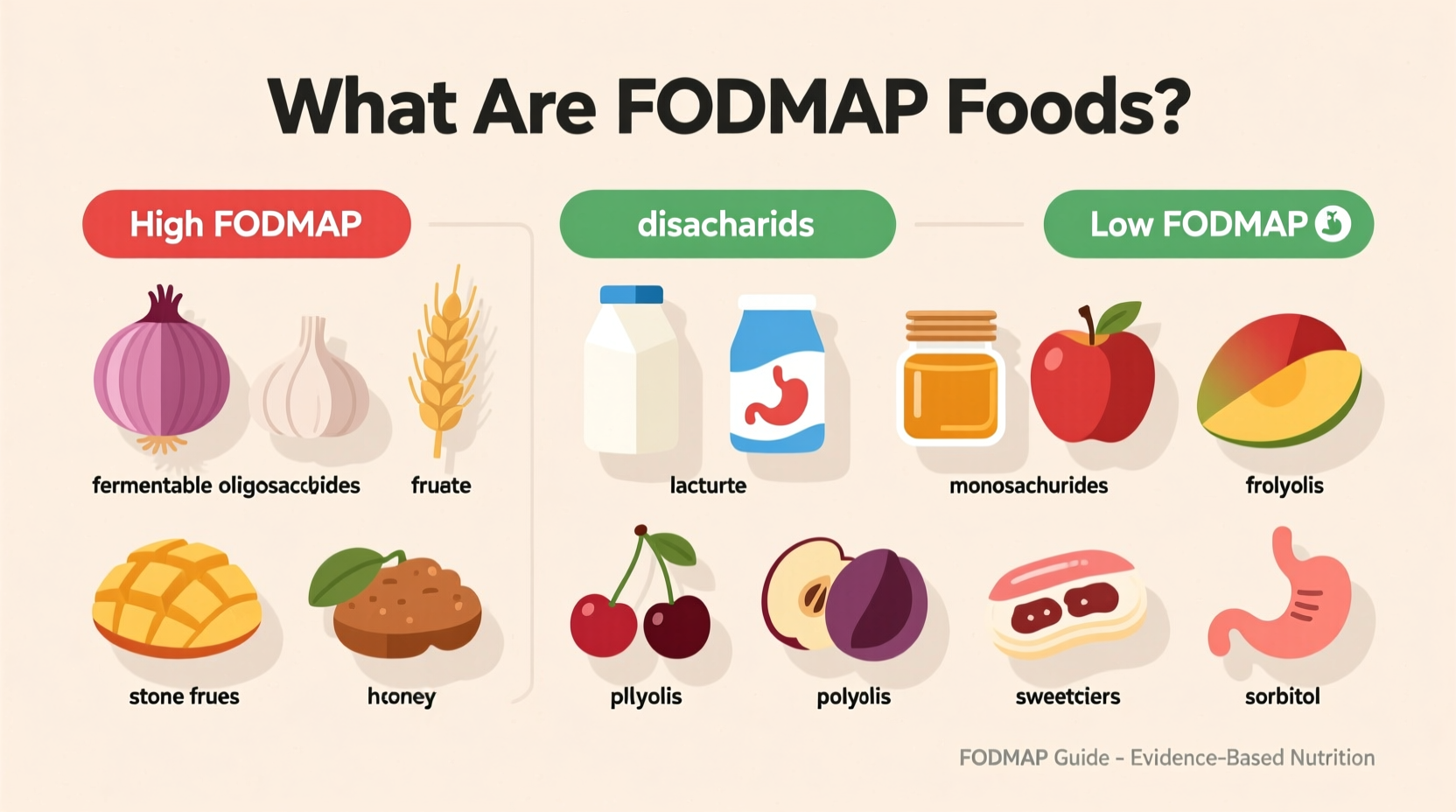

FODMAP is an acronym representing five categories of fermentable carbohydrates that can cause digestive distress:

- Fermentable: Easily broken down by gut bacteria, producing gas

- Oligosaccharides: Includes fructans (found in wheat, onions, garlic) and galacto-oligosaccharides (found in legumes)

- Disaccharides: Primarily lactose (found in dairy products)

- Monosaccharides: Specifically excess fructose (found in apples, pears, honey)

- Polyols: Sugar alcohols like sorbitol and mannitol (found in stone fruits and artificial sweeteners)

These short-chain carbohydrates draw water into the intestine and ferment rapidly when they reach the colon, which can trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals. Research from Monash University, the pioneers of the low-FODMAP diet, shows that approximately 75% of people with IBS experience significant symptom improvement when following this dietary approach.

High-FODMAP Foods to Recognize

Certain food groups contain higher concentrations of FODMAPs. Recognizing these can help you make informed dietary choices:

| Food Category | High-FODMAP Examples | Low-FODMAP Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

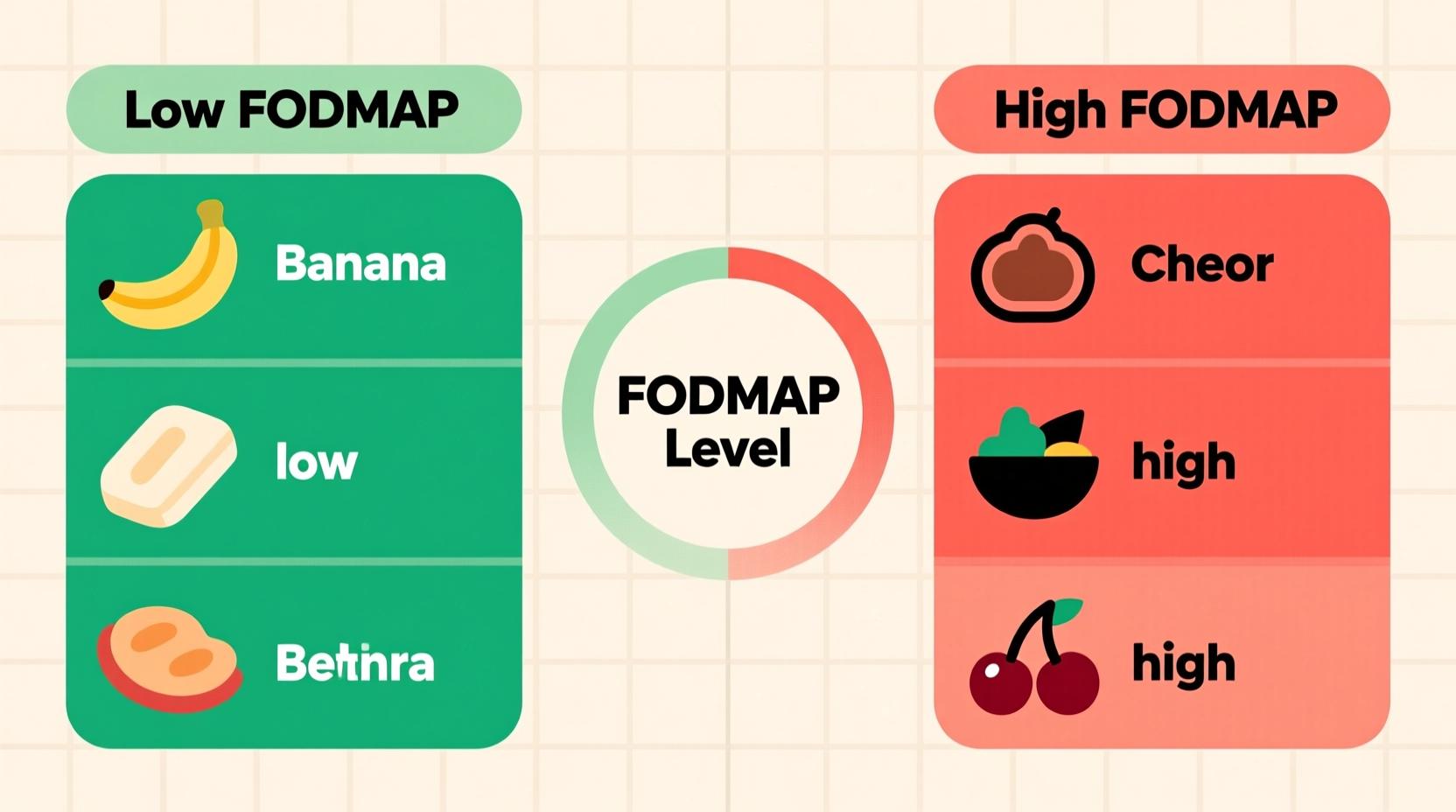

| Fruits | Apples, pears, mangoes, watermelon | Bananas (firm), berries, citrus fruits, grapes |

| Vegetables | Onions, garlic, cauliflower, asparagus | Carrots, zucchini, bell peppers, spinach |

| Dairy | Milk, yogurt, soft cheeses | Lactose-free milk, hard cheeses, almond milk |

| Grains | Wheat, rye, barley | Oats, rice, quinoa, gluten-free products |

| Sweeteners | Honey, high-fructose corn syrup, agave | Maple syrup, glucose, stevia |

The Three-Phase Low-FODMAP Approach

The low-FODMAP diet follows a structured timeline developed through clinical research at Monash University. This evidence-based approach includes three distinct phases:

- Elimination Phase (2-6 weeks): Strictly remove high-FODMAP foods to allow your digestive system to settle. Most people notice symptom improvement within this timeframe if FODMAPs are their primary trigger.

- Reintroduction Phase (8-12 weeks): Systematically reintroduce specific FODMAP groups one at a time to identify which carbohydrates trigger your symptoms. This phase requires careful tracking and patience.

- Personalization Phase (Ongoing): Create a modified low-FODMAP diet based on your individual tolerance levels. Most people can eventually reintroduce some FODMAPs, creating a more varied and sustainable eating pattern.

According to the International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders, this phased approach helps 50-80% of IBS patients identify specific food triggers while maintaining nutritional balance (aboutibs.org). The American College of Gastroenterology recognizes the low-FODMAP diet as a first-line dietary therapy for managing IBS symptoms (gi.org).

Who Benefits Most from FODMAP Awareness?

While anyone can learn about FODMAP foods, this knowledge provides the greatest benefit for specific populations:

- Individuals diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- People with functional gastrointestinal disorders

- Those experiencing chronic bloating, gas, or abdominal discomfort

- Individuals with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

It's crucial to understand the context boundaries: The low-FODMAP diet is not recommended as a general weight-loss strategy or for people without digestive symptoms. Monash University researchers emphasize that this should be implemented under professional guidance, as unnecessarily restricting FODMAPs long-term can negatively impact gut microbiome diversity (monashfodmap.com).

Practical Daily Management Strategies

Successfully navigating FODMAP foods requires more than just knowing which items to avoid. Implement these practical approaches:

- Read labels carefully: Look for hidden FODMAPs like inulin, chicory root, and high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods

- Use portion control: Some high-FODMAP foods are tolerable in small quantities (e.g., 1/4 avocado instead of a whole one)

- Track your symptoms: Maintain a detailed food and symptom journal during the reintroduction phase

- Plan restaurant meals: Research menus in advance and don't hesitate to request modifications

- Work with a professional: Consult a registered dietitian specializing in digestive health for personalized guidance

Common Misconceptions Clarified

Several myths surround FODMAP foods that deserve clarification:

- Myth: The low-FODMAP diet is a permanent solution

Fact: It's designed as a temporary elimination diet followed by strategic reintroduction to identify personal triggers - Myth: All high-FODMAP foods are unhealthy

Fact: Many high-FODMAP foods like garlic, onions, and legumes are nutritious—they're only problematic for certain individuals - Myth: FODMAP sensitivity means you have a food allergy

Fact: FODMAP reactions are digestive intolerances, not immune responses like true food allergies

Getting Started with FODMAP Awareness

If you're considering exploring FODMAP foods for digestive health improvement, begin with these steps:

- Consult with your healthcare provider to rule out other medical conditions

- Download the Monash University FODMAP app for comprehensive food database access

- Consider working with a registered dietitian experienced in the low-FODMAP protocol

- Start a symptom journal before making any dietary changes

- Begin with the elimination phase only after proper preparation and education

Remember that everyone's digestive system responds differently. What triggers symptoms in one person may be perfectly tolerable for another. The goal isn't complete FODMAP elimination but rather identifying your personal tolerance thresholds for improved digestive comfort.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4