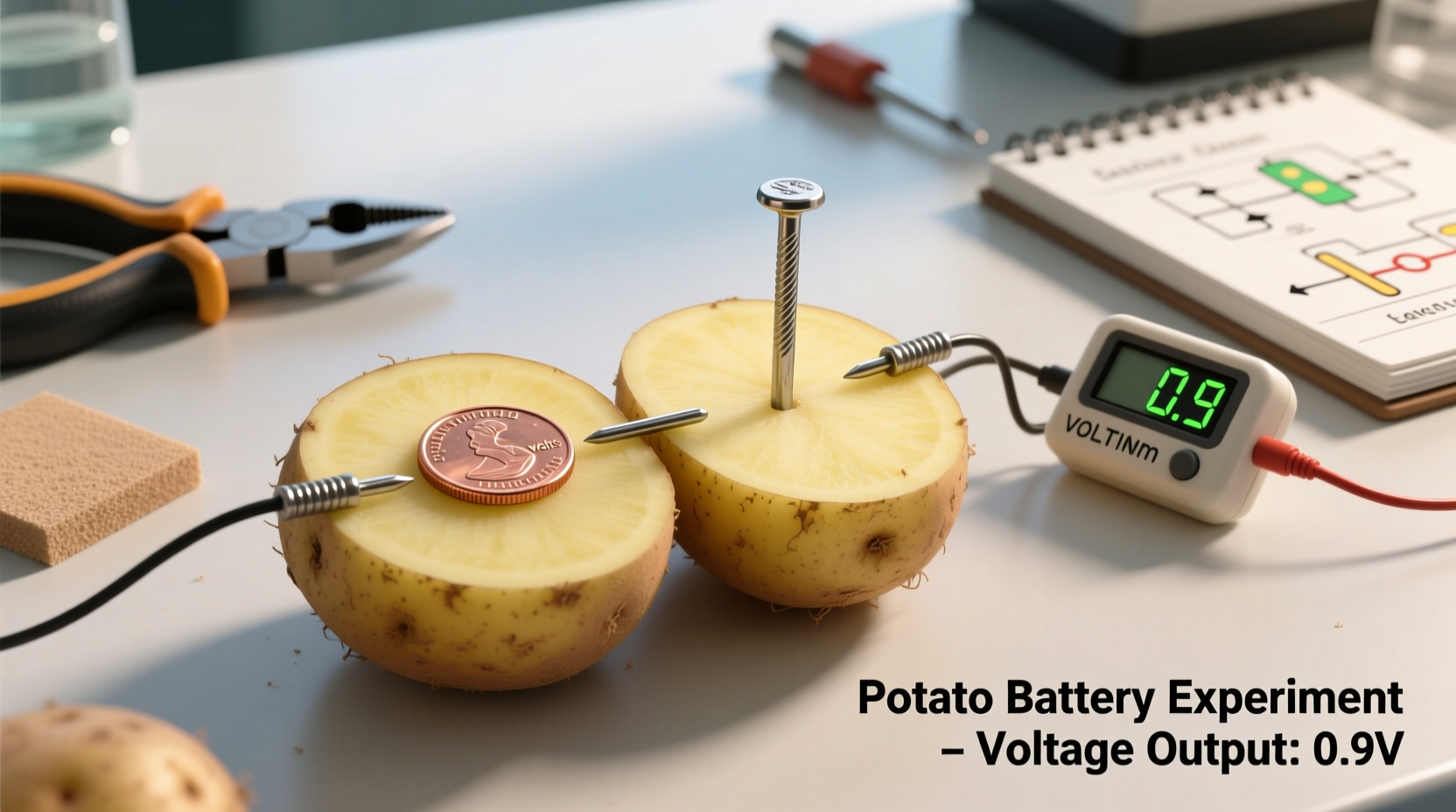

If you're searching for information about a "voice meter potato," you're likely referring to the classic potato battery experiment where a multimeter (sometimes mistakenly called a voice meter) measures electrical voltage generated by a potato. This simple science experiment demonstrates basic electrochemical principles using everyday materials. A properly constructed potato battery typically produces 0.5-0.8 volts of electricity, enough to power small LED lights or digital clocks when multiple potatoes are connected in series.

Understanding the Potato Battery Experiment

When people search for "voice meter potato," they're usually looking for instructions on the popular potato battery science project. The term "voice meter" appears to be a common mishearing of "voltage meter" or multimeter, the device used to measure the electrical output from a potato-based battery. This hands-on experiment serves as an excellent introduction to electrochemistry for students and curious learners.

Why Potatoes Work as Batteries

Potatoes contain phosphoric acid, which acts as an electrolyte enabling the chemical reaction between two different metal electrodes. When you insert zinc and copper electrodes into a potato, a redox reaction occurs:

- Zinc electrode oxidizes: Zn → Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻

- Copper electrode facilitates reduction: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂

This movement of electrons creates a small electrical current that can be measured with a multimeter and potentially used to power small electronic devices.

| Produce Item | Average Voltage (Single Cell) | Best Electrode Pair |

|---|---|---|

| Potato (raw) | 0.5-0.8V | Zinc/Copper |

| Lemon | 0.9-1.0V | Zinc/Copper |

| Apple | 0.6-0.7V | Zinc/Copper |

| Tomato | 0.7-0.9V | Magnesium/Copper |

Materials You'll Need

To successfully create and measure your potato battery, gather these materials:

- 2-4 medium-sized potatoes (firm and fresh)

- Copper electrodes (copper nails or strips)

- Zinc electrodes (galvanized nails or zinc strips)

- Insulated wires with alligator clips

- Digital multimeter (voltage meter)

- Small LED light or digital clock (optional, for demonstration)

- Knife for preparing potatoes

Step-by-Step Measurement Process

Follow these steps to build your potato battery and accurately measure its voltage output:

- Prepare the potatoes: Wash and dry 2-4 potatoes. Cut a small slit in each potato to make electrode insertion easier.

- Insert electrodes: Push one copper and one zinc electrode into each potato, about 2 inches apart. Ensure they don't touch inside the potato.

- Set up your multimeter: Turn the dial to DC voltage (usually marked as V with a straight line). Set the range to 2V or the lowest setting above 1V.

- Connect the first potato: Attach the red (positive) probe to the copper electrode and the black (negative) probe to the zinc electrode.

- Record initial reading: Note the voltage (typically 0.5-0.8V for a single potato).

- Create a series circuit: Connect multiple potatoes by linking the zinc electrode of one potato to the copper electrode of the next using wires with alligator clips.

- Measure combined output: Test the total voltage across the entire series (two potatoes should produce 1.0-1.6V).

- Test with a load: Connect a small LED or digital clock to see if your battery can power it.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

If your potato battery isn't producing expected results, consider these factors:

- Electrode spacing: Electrodes too close may short-circuit; too far reduces efficiency. Maintain 1.5-2 inches between electrodes.

- Potato freshness: Older potatoes have less moisture and acid content. Use firm, fresh potatoes for best results.

- Electrode material: Pure copper and zinc work best. Avoid coated or painted metals.

- Temperature: Warmer temperatures increase reaction rate. Room temperature (68-72°F) works well.

- Electrode surface area: More surface contact with potato increases current. Try wider strips instead of nails.

Educational Applications and Learning Outcomes

The potato battery experiment aligns with multiple educational standards and offers valuable learning opportunities:

According to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), this activity supports MS-PS1-2 (analyzing and interpreting data on chemical reactions) and MS-PS2-3 (electric and magnetic forces). The National Science Teaching Association recognizes this as an effective hands-on activity for demonstrating energy conversion principles.

| Year | Scientist | Contribution | Voltage Produced |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1780 | Luigi Galvani | Discovered "animal electricity" using frog legs | N/A |

| 1800 | Alessandro Volta | Invented first true battery (Voltaic Pile) | 0.76V per cell |

| 1840s | John Frederic Daniell | Created more stable Daniell cell | 1.1V |

| 1866 | Georges Leclanché | Developed zinc-carbon battery | 1.5V |

| 1868 | Gaston Planté | Invented lead-acid battery | 2.0V per cell |

Maximizing Your Potato Battery's Performance

Research from the Science Buddies organization shows several techniques to increase your potato battery's output:

- Boiling potatoes: Heating potatoes for 8-10 minutes increases ion mobility, potentially doubling voltage output.

- Electrode arrangement: Parallel electrodes produce more current than perpendicular arrangements.

- Multiple connection points: Using multiple electrode pairs per potato creates parallel circuits within a single potato.

- Acid enhancement: Adding small amounts of vinegar or lemon juice can boost performance (though this moves away from the "pure" potato experiment).

Real-World Context and Limitations

While the potato battery makes an excellent educational tool, it's important to understand its practical limitations:

- Energy density: A potato battery has extremely low energy density compared to commercial batteries (about 500,000 times less efficient than alkaline batteries).

- Practical applications: The experiment demonstrates principles but isn't viable for real-world power needs beyond educational demonstrations.

- Environmental factors: Performance varies significantly with potato variety, freshness, temperature, and electrode materials.

- Safety considerations: While safe for educational use, never attempt to scale up this experiment significantly as it could create electrical hazards.

According to a study published in the Journal of Chemical Education, potato batteries typically deliver only 0.2-0.3 mA of current, sufficient for small LEDs but inadequate for most practical applications. The experiment's true value lies in its ability to make abstract electrochemical concepts tangible for learners.

Advanced Variations for Enthusiasts

Once you've mastered the basic potato battery, try these advanced variations:

- Comparative testing: Measure voltage output from different potato varieties (Russet, Yukon Gold, red potatoes) to determine which works best.

- Temperature effects: Test how heating or cooling potatoes affects voltage output.

- Multiple configurations: Experiment with series versus parallel connections to understand their different effects on voltage and current.

- Alternative produce: Compare potatoes with other fruits and vegetables to identify which natural materials make the most effective batteries.

For science fair projects, consider documenting how variables like potato size, electrode depth, or resting time after insertion affect performance. These investigations develop valuable scientific thinking skills while exploring electrochemical principles.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4