From Tongue to Brain: The Flavor Perception Journey

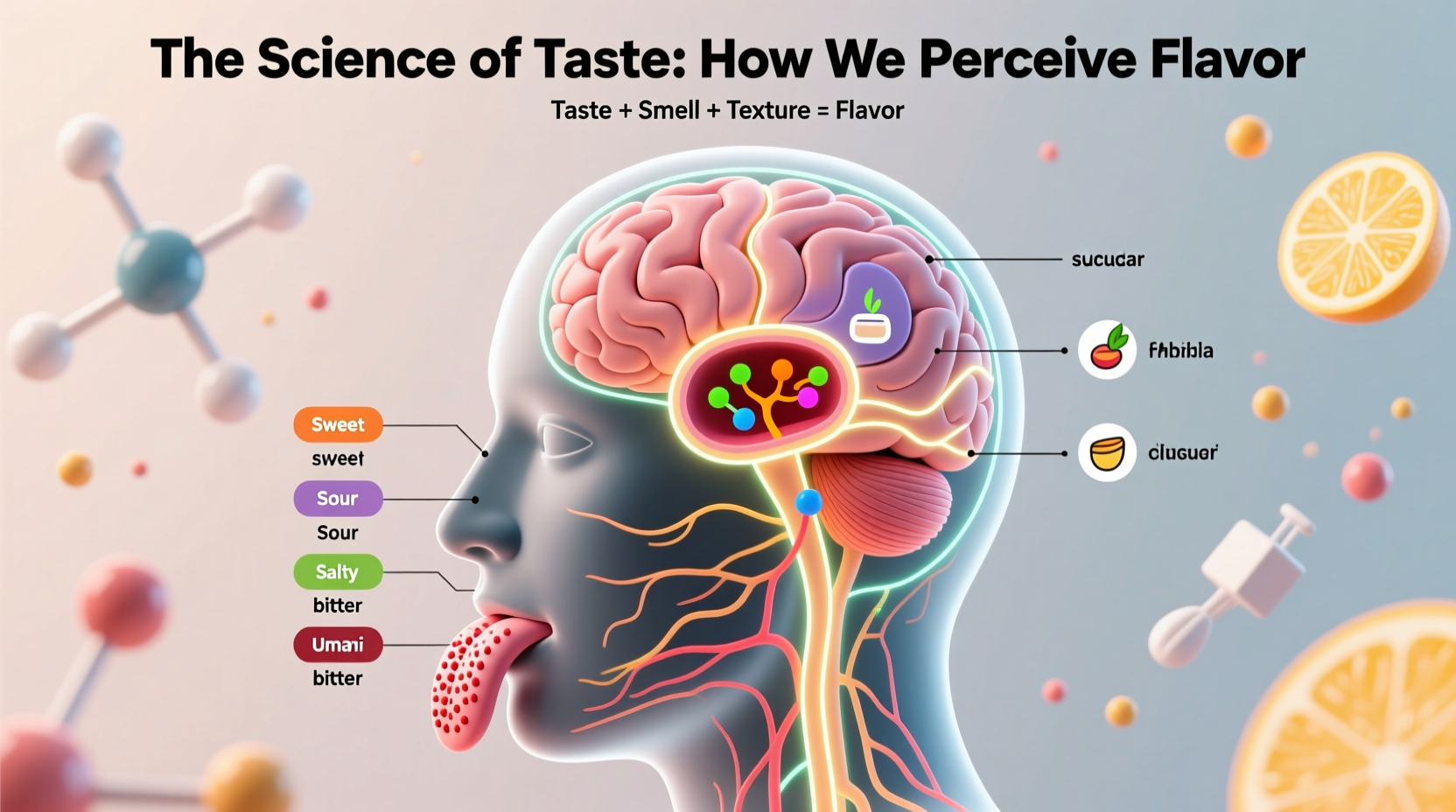

When you take a bite of food, the process of flavor perception begins immediately. Taste buds on your tongue contain specialized receptor cells that detect chemical compounds in food. These receptors send signals through cranial nerves to the gustatory cortex in the brain. But here's what most people don't realize: what we call “taste” is actually only 20% of the flavor experience.

The Critical Role of Smell in Flavor Perception

Ever notice how food seems bland when you have a stuffy nose? That's because approximately 80% of what we perceive as flavor comes from our sense of smell. When you chew, volatile compounds travel through the retronasal pathway to olfactory receptors in your nasal cavity. This is why pinching your nose while eating dramatically reduces flavor intensity.

| Sensory Component | Contribution to Flavor | Key Detection Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Taste (gustation) | 20% | Taste buds on tongue |

| Smell (olfaction) | 80% | Olfactory receptors |

| Mouthfeel | 15% | Trigeminal nerve |

| Visual cues | 10-20% | Visual cortex |

How Your Brain Constructs Flavor

Flavor isn't something that exists in food itself—it's created by your brain. Neuroimaging studies from the Monell Chemical Senses Center show that flavor perception involves multiple brain regions working together:

- The primary gustatory cortex processes basic taste qualities

- The orbitofrontal cortex integrates taste, smell, and texture information

- The hippocampus links flavors to memories and emotions

- The insula processes the emotional response to food

This neural integration explains why the same food can taste different depending on context, mood, or even the color of the plate it's served on. Research published in Chemical Senses demonstrates that visual cues can alter perceived sweetness by up to 10%, showing how deeply interconnected our sensory systems are.

Individual Differences in Taste Perception

Not everyone experiences flavor the same way. Genetic variations significantly impact taste sensitivity:

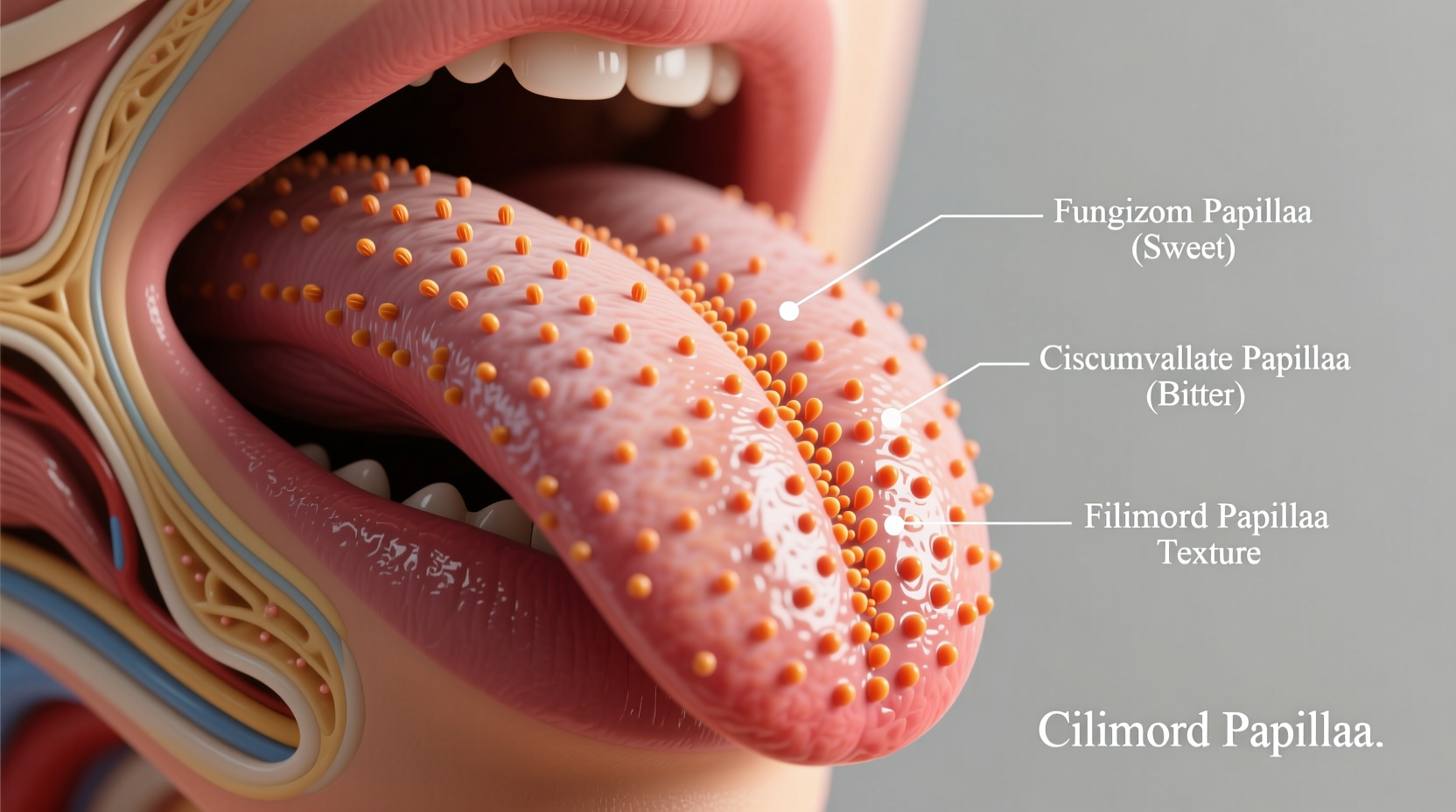

Approximately 25% of people are "supertasters" with heightened sensitivity to bitter compounds like PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil), according to research from the National Institutes of Health. These individuals have more fungiform papillae on their tongues, making certain vegetables like broccoli taste intensely bitter. Conversely, "non-tasters" may require significantly more seasoning to perceive the same flavor intensity.

Age also dramatically affects flavor perception. The American Chemical Society reports that humans begin losing taste buds around age 40, with a 50% reduction by age 70. This explains why older adults often prefer stronger flavors and why children typically reject bitter vegetables that adults learn to appreciate.

Practical Applications of Flavor Science

Understanding the science of taste isn't just academic—it has real-world applications for everyday cooking and eating:

Enhancing Flavors Without Extra Salt or Sugar

By leveraging umami-rich ingredients like tomatoes, mushrooms, and aged cheeses, you can create satisfying flavors with less sodium. The Food and Drug Administration recognizes that umami compounds can reduce sodium content by up to 40% while maintaining perceived saltiness.

Optimizing Food Pairings Based on Flavor Chemistry

Certain flavor compounds naturally complement each other. For example, the vanillin in chocolate shares chemical similarities with the eugenol in cinnamon, creating a harmonious pairing. Understanding these molecular relationships helps create balanced dishes that satisfy the brain's flavor expectations.

Managing Taste Changes During Illness

When recovering from respiratory infections, many people experience altered taste perception. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that smell training with essential oils can help restore normal flavor perception by retraining olfactory receptors. Simple techniques like using brightly colored foods can also enhance flavor perception when smell is compromised.

Why Flavor Perception Evolved as a Survival Mechanism

Our sophisticated flavor perception system didn't develop by accident. Evolutionary biologists from Harvard University explain that taste preferences evolved as survival mechanisms:

- Sweet preference signaled energy-rich carbohydrates

- Bitter aversion protected against potential toxins

- Salt craving ensured adequate electrolyte intake

- Umami detection helped identify protein sources

This evolutionary framework explains why certain flavor preferences are nearly universal across cultures, while others develop through exposure and learning. Modern food science continues to uncover how these ancient survival mechanisms interact with today's food environment.

Common Questions About Taste Perception

Why does food taste different when I have a cold?

When you have a cold, nasal congestion blocks the retronasal passage that carries aroma compounds to your olfactory receptors. Since smell contributes approximately 80% of flavor perception, this significantly reduces your ability to detect nuanced flavors, making food seem bland.

What are supertasters and how common are they?

Supertasters have a genetic variation that gives them more taste buds and heightened sensitivity to certain flavors, particularly bitter compounds. Approximately 25% of the population are supertasters, 50% are medium tasters, and 25% are non-tasters, according to research from the National Institutes of Health.

Can taste preferences change over time?

Yes, taste preferences can change significantly through repeated exposure. The brain's flavor processing system is neuroplastic, meaning repeated positive experiences with a food can create new neural pathways. This is why children often reject vegetables like Brussels sprouts but may learn to enjoy them as adults.

Why does coffee taste bitter to some people but not others?

Genetic differences in the TAS2R38 receptor gene affect sensitivity to bitter compounds like caffeine. Supertasters with certain genetic variants perceive coffee as intensely bitter, while others with different variants may barely detect the bitterness, explaining why some people enjoy black coffee while others need significant sweetening.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4