The Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852) caused approximately 1 million deaths and forced 1-2 million Irish people to emigrate, reducing Ireland's population by 20-25%. Triggered by the potato blight Phytophthora infestans, this humanitarian crisis was exacerbated by British government policies, land tenure systems, and Ireland's extreme dependence on the potato as a staple crop for the rural poor.

| Year | Population | Change from Previous Census |

|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 8,175,124 | N/A |

| 1851 | 6,552,385 | -19.9% |

| 1861 | 5,798,564 | -11.6% (from 1851) |

Understanding Ireland's Vulnerability Before the Blight

Before the famine struck, Ireland's agricultural system had developed a dangerous dependency on the potato. By the 1840s, nearly half of Ireland's population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance. Small tenant farmers typically cultivated just 1-2 acres of land, dedicating most of it to potato cultivation because a single acre could feed a family of six for an entire year.

This dependency stemmed from historical land policies that concentrated ownership among British absentee landlords. The Irish Census Archives reveal that by 1845, approximately 50% of Irish agricultural land was held in plots smaller than 5 acres, creating widespread vulnerability when the potato crop failed.

The Blight's Devastating Timeline

Understanding the progression of the Irish Potato Famine requires examining its chronological development:

1845: First Appearance of the Blight

In September 1845, farmers noticed their potato plants turning black and rotting in the fields. The mysterious disease, later identified as Phytophthora infestans, destroyed approximately one-third of that year's potato crop. The British government established a Relief Commission but provided limited assistance.

1846: Catastrophic Failure and Policy Missteps

The blight returned with greater intensity, destroying 75% of the potato crop. Prime Minister Robert Peel secretly purchased maize from the United States, but distribution problems and the unfamiliarity of "peelers" (imported corn) limited its effectiveness. The government repealed the Corn Laws but maintained laissez-faire economic policies that prevented adequate intervention.

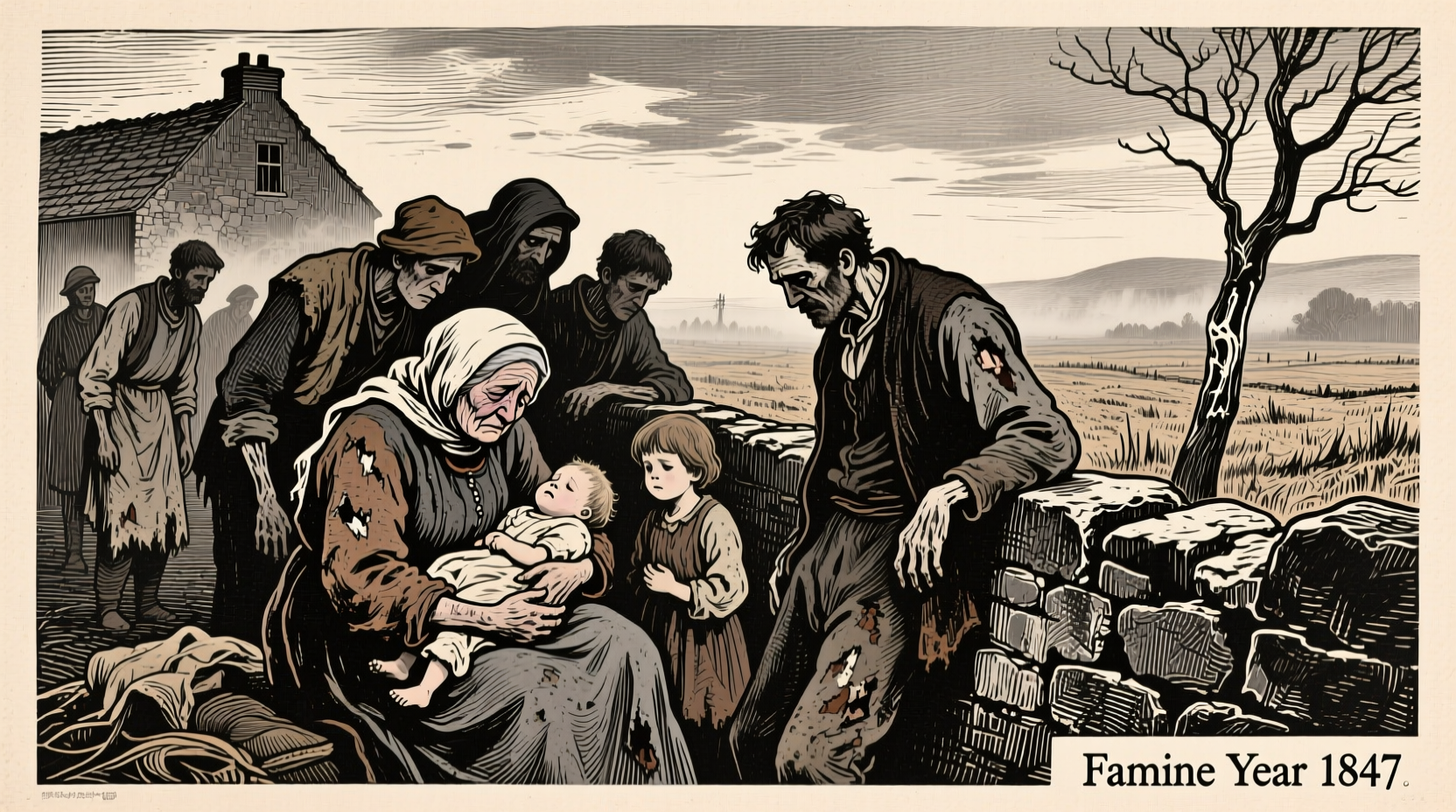

1847: "Black '47" - The Worst Year

Known as "Black '47," this year saw the highest mortality rates as the potato crop failed completely in many regions. Workhouses overflowed, and fever epidemics spread through malnourished populations. The government shifted responsibility to local poor rates, which proved inadequate for the scale of the crisis.

1848-1852: Continued Suffering and Mass Emigration

Though the blight recurred less severely after 1847, the damage was done. With no capital to restart farming operations and facing continued evictions, hundreds of thousands chose emigration. By 1851, Ireland's population had decreased by nearly 2 million through death and emigration.

Human Cost: Beyond the Numbers

The statistics tell only part of the story. According to records from the National Archives of Ireland, the famine's impact varied dramatically by region. The west and southwest of Ireland, where dependence on the potato was greatest, suffered most severely. In some counties, population decline exceeded 30%.

Contemporary accounts describe heartbreaking scenes: families huddled in collapsed cabins, mass graves where bodies were buried without coffins, and emigrant ships known as "coffin ships" where mortality rates sometimes reached 30%. The Great Famine fundamentally altered Irish society, destroying the Irish language in many regions and transforming land ownership patterns permanently.

Government Response and Historical Debate

Scholars continue to debate the adequacy of the British government's response. While some relief efforts were implemented, including public works programs and soup kitchens, many historians argue these were insufficient and poorly administered. The doctrine of laissez-faire economics prevented more direct intervention, and food continued to be exported from Ireland to Britain throughout the famine years.

According to research from Trinity College Dublin's Department of History, approximately 4,000 shiploads of food left Irish ports for England during the famine period. This historical context remains controversial, with some scholars characterizing the famine as a preventable tragedy exacerbated by political decisions.

Lasting Impact on Ireland and the World

The demographic consequences of the Irish Potato Famine continue to shape Ireland today. Ireland remains the only European country with a smaller population now than in 1840. The famine triggered mass emigration that created the Irish diaspora, particularly in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Britain.

Culturally, the famine left deep psychological scars that influenced Irish attitudes toward land, food security, and British rule for generations. It also transformed Irish agriculture, reducing dependence on the potato and encouraging diversification. The memory of the famine continues to inform Irish identity and historical consciousness, with memorials around the world honoring those who suffered and perished.

Frequently Asked Questions

What caused the Irish Potato Famine?

The immediate cause was Phytophthora infestans, a potato blight that destroyed the primary food source for Ireland's rural poor. However, underlying causes included Ireland's extreme dependence on the potato, British land policies, economic structures that prioritized grain exports from Ireland, and inadequate government response to the crisis.

How many people died during the Irish Potato Famine?

Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases between 1845 and 1852. This represented about 12.5% of Ireland's pre-famine population. Mortality rates were highest in 1847, known as "Black '47," when fever epidemics spread through malnourished populations.

Why did the British government's response fail to prevent mass starvation?

The British government initially adhered to laissez-faire economic principles that limited direct food aid. Relief efforts like public works programs required exhausting labor from starving people. Food exports from Ireland to Britain continued throughout the famine. Soup kitchens were eventually established but were discontinued after just six months. Many historians argue the response was inadequate for the scale of the crisis.

How did the famine change Irish society permanently?

The famine reduced Ireland's population by 20-25% through death and emigration. It destroyed the Irish language in many regions, transformed land ownership patterns, created the Irish diaspora worldwide, and left deep psychological scars that influenced Irish attitudes toward food security and British rule for generations. Ireland remains the only European country with a smaller population now than in 1840.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4