The Great Potato Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, occurred in Ireland between 1845 and 1852. Caused by a devastating potato blight (Phytophthora infestans), this catastrophic event led to approximately 1 million deaths from starvation and disease, while forcing another 1-2 million Irish citizens to emigrate. The famine fundamentally reshaped Ireland's demographic, cultural, and political landscape, with Ireland's population never recovering to pre-famine levels even today.

When searching for information about the Great Potato Famine, you need accurate historical context, verified statistics, and a clear understanding of why this event remains significant nearly two centuries later. This comprehensive guide delivers precisely that—separating historical fact from common misconceptions while providing the essential information you're seeking about one of history's most devastating food crises.

Understanding the Great Potato Famine: Beyond the Basic Facts

The Great Potato Famine wasn't merely a natural disaster—it represented a perfect storm of biological catastrophe, political mismanagement, and socioeconomic vulnerability. While the immediate trigger was Phytophthora infestans, the microscopic fungus that destroyed potato crops, the famine's severity stemmed from Ireland's dangerous dependence on a single crop combined with British colonial policies that limited effective relief efforts.

The Timeline That Changed Ireland Forever

Understanding the progression of the Great Hunger requires examining its critical timeline. This chronological perspective reveals how a biological disaster escalated into a humanitarian catastrophe:

| Year | Key Events | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | First appearance of potato blight in Ireland; destroyed approximately 1/3 of the crop | Initial food shortages, but alternative crops remained available |

| 1846 | Blight returned with greater severity; destroyed 3/4 of potato crop; British government suspended Corn Laws | Widespread starvation began; export of other food crops from Ireland continued |

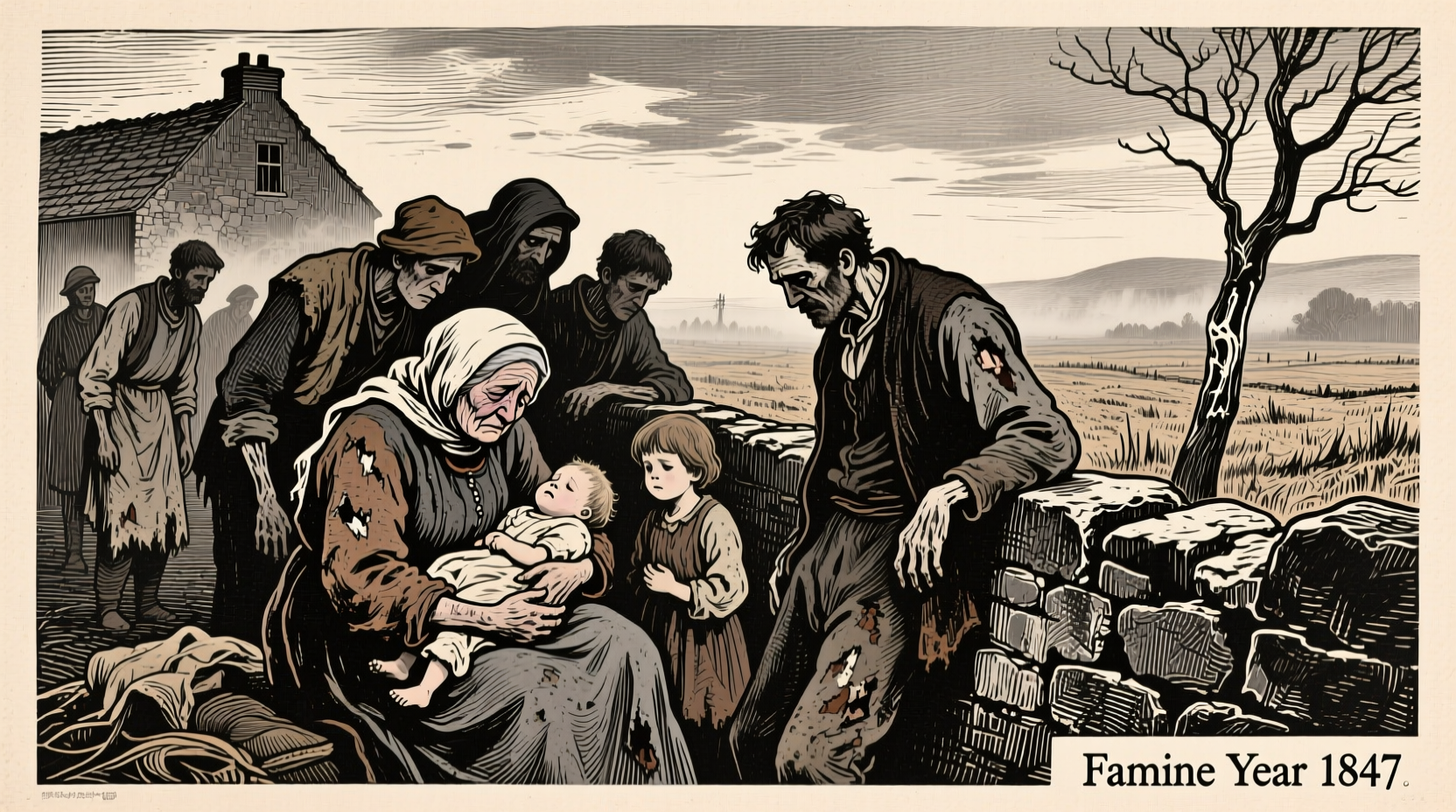

| 1847 | "Black '47"—worst year of famine; soup kitchens established then closed; workhouses overwhelmed | Peak mortality; mass emigration began; disease epidemics spread |

| 1848-1852 | Recurring blight; limited recovery; Young Irelander Rebellion | Continued emigration; permanent demographic shift; cultural trauma |

Why Was Ireland So Vulnerable to Potato Failure?

To understand the Great Famine's severity, we must examine Ireland's unique socioeconomic conditions in the mid-19th century:

- Monoculture dependence: By 1845, over 3 million Irish people relied almost exclusively on potatoes for sustenance, with many consuming 8-14 pounds daily

- Land tenure system: Absentee British landlords controlled most Irish land, with tenant farmers paying rent through cash crops rather than food production

- Political context: Ireland was part of the United Kingdom but lacked political autonomy to implement effective relief measures

- Economic structure: Despite food exports continuing during the famine, Ireland remained a net exporter of food to Britain

Human Cost: Beyond the Numbers

While statistics convey part of the story, the human impact of the Great Hunger transcends mere numbers. According to Ireland's Central Statistics Office and census records from the period:

- Ireland's population declined by 20-25% between 1841-1851 through death and emigration

- Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases like typhus and cholera

- Between 1-2 million people emigrated, primarily to North America and Britain

- Life expectancy in Ireland dropped from 40 years to 19 years during peak famine years

British Government Response: Policy Failures and Consequences

The British government's approach to the famine remains controversial among historians. Initially, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel authorized limited relief measures, including secret purchase of American corn. However, after Peel's government fell in 1846, his successor Lord John Russell adopted a policy of non-intervention based on laissez-faire economic principles.

Key policy decisions that worsened the crisis included:

- Maintaining food exports from Ireland during the famine years

- Requiring Irish landowners to pay for relief through local taxes, leading to mass evictions

- Terminating soup kitchens in 1847, just as the crisis peaked

- Insisting that relief should come through workhouses rather than direct food aid

Common Misconceptions About the Great Famine

Several persistent myths obscure our understanding of this historical tragedy:

| Misconception | Historical Reality | Source Verification |

|---|---|---|

| "The British deliberately caused the famine to eliminate Irish people" | While policies worsened the crisis, there's no evidence of deliberate genocide; the famine resulted from complex factors including biological disaster and policy failures | National Famine Museum, Strokestown Park, Ireland |

| "Only potatoes failed during the famine" | Other crops like wheat, oats, and livestock continued to be produced and exported from Ireland throughout the famine years | Irish Historical Documents Archive, University College Dublin |

| "The famine ended when the blight disappeared" | Recurring blight continued through 1852; social and economic impacts persisted for decades | Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Ireland |

Lasting Impact on Ireland and the World

The Great Famine's legacy extends far beyond the immediate crisis. Its long-term consequences include:

- Demographic collapse: Ireland's population has never recovered to pre-famine levels; today's population remains below 1841 figures

- Diaspora formation: Created massive Irish communities in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Britain that continue to influence global culture

- Political transformation: Fueled Irish nationalism and eventually contributed to Ireland's independence movement

- Cultural trauma: Created a lasting psychological impact known as "famine memory" that influences Irish identity to this day

- Agricultural change: Ended Ireland's dangerous dependence on potato monoculture

Why the Great Potato Famine Matters Today

Understanding this historical event provides crucial lessons for contemporary challenges. The famine demonstrates how food security depends not just on crop production but on equitable distribution systems, responsive governance, and diversified agricultural practices. Modern food crises in various parts of the world echo similar patterns of vulnerability that made Ireland susceptible to catastrophe in the 1840s.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly caused the Great Potato Famine?

The immediate cause was Phytophthora infestans, a microscopic fungus that destroyed potato crops. However, the famine's severity resulted from Ireland's extreme dependence on potatoes combined with British colonial policies that limited effective relief efforts and allowed food exports to continue during the crisis.

How many people died during the Irish Potato Famine?

Approximately 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases between 1845-1852. This represented about one-eighth of Ireland's pre-famine population, with an additional 1-2 million people forced to emigrate.

Why didn't people eat other foods during the famine?

While other food crops like wheat, oats, and livestock were produced in Ireland during the famine, they were primarily grown for export to Britain. Most Irish tenant farmers were required to pay rent through cash crops rather than food production, leaving them without access to alternative food sources when the potato crop failed.

How did the Great Famine change Ireland permanently?

The famine caused permanent demographic collapse (Ireland's population remains below pre-famine levels), created a massive global Irish diaspora, transformed Irish agriculture away from potato monoculture, and fueled Irish nationalism that eventually led to independence from Britain.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4