Understanding potato species transforms how you select, cook, and appreciate this essential global crop. Whether you're a home cook seeking perfect mashed potatoes, a gardener wanting disease-resistant varieties, or simply curious about the botanical diversity behind your favorite tuber, this guide delivers actionable knowledge about potato classification, characteristics, and practical applications.

Botanical Classification: Beyond Grocery Store Labels

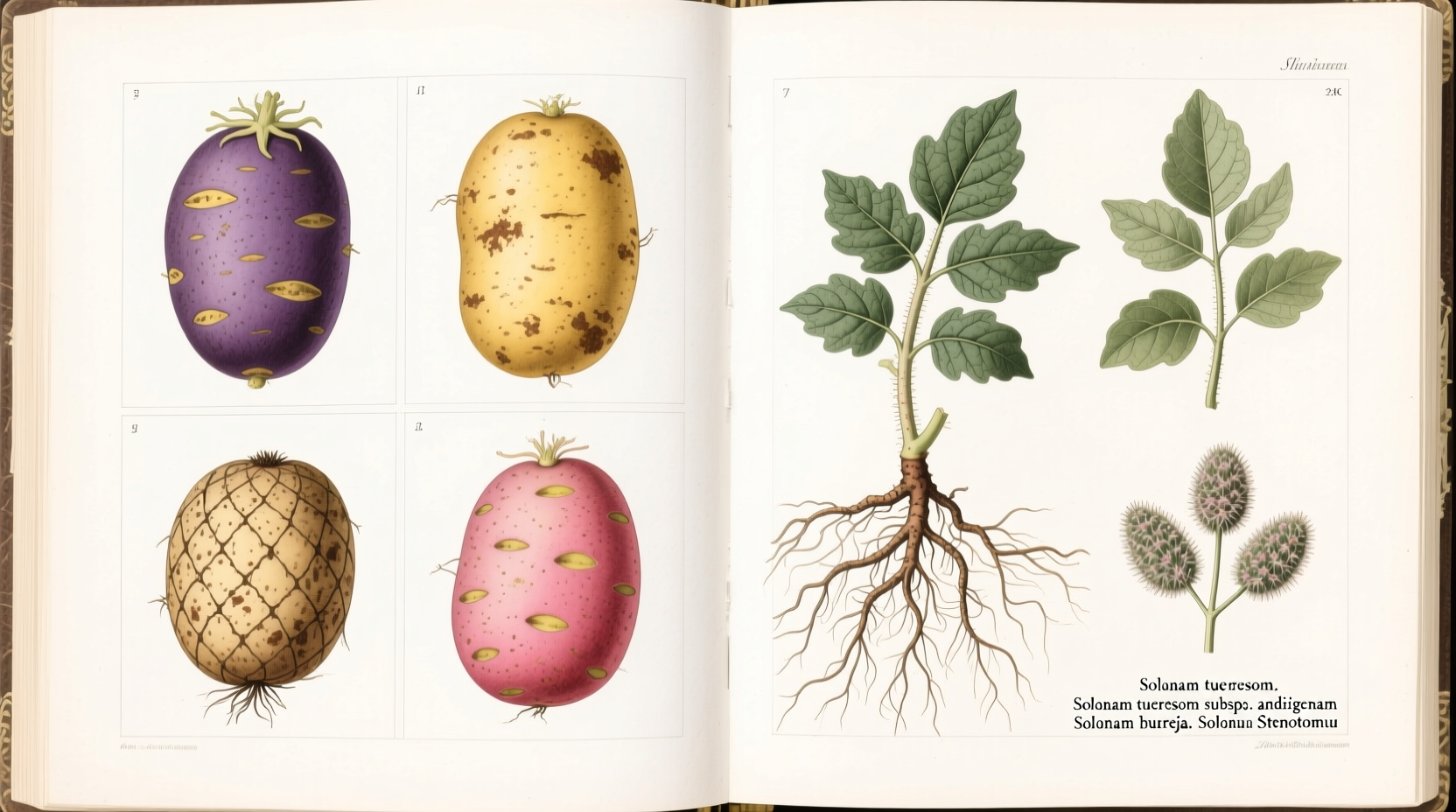

When discussing "species of potato," we're referring to distinct biological classifications within the Solanum genus. While consumers typically encounter varieties labeled as "russet," "Yukon Gold," or "red," these represent cultivars within the primary species Solanum tuberosum. True species differ in chromosome count, origin, and genetic characteristics.

| Species | Chromosome Count | Primary Growing Region | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum tuberosum | 48 (tetraploid) | Global | Commercial varieties, diverse skin/texture, 99% of production |

| Solanum andigenum | 24-48 (diploid to tetraploid) | Andes Mountains | Day-length sensitive, colorful tubers, frost-tolerant |

| Solanum ajanhuiri | 24 (diploid) | High-altitude Andes | Resistant to frost and late blight, small tubers |

| Solanum juzepczukii | 36 (triploid) | Peruvian Altiplano | Extreme cold tolerance, used for chuño (freeze-dried potatoes) |

| Solanum stenotomum | 24 (diploid) | Central Andes | Earliest domesticated form, diverse colors, low yield |

This fact对照 table from the International Potato Center (CIP) clarifies how different potato species vary in genetic structure and adaptation. Unlike grocery store varieties which are cultivars within S. tuberosum, these species represent distinct evolutionary branches developed over millennia in South America's diverse ecosystems. Understanding these differences explains why certain potatoes thrive in specific climates while others excel in particular culinary applications.

Historical Development of Cultivated Species

Potatoes originated in the Andean region of South America approximately 8,000 years ago. The domestication process created distinct species adapted to varying altitudes and microclimates:

- 8,000-7,000 BCE: Initial domestication of wild potatoes in southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia

- 4,000 BCE: Development of Solanum stenotomum, the first cultivated species

- 2,000 BCE: Emergence of Solanum tuberosum group in lowland regions

- 1,500 CE: Spanish conquistadors introduce potatoes to Europe

- 1845-1852: Irish Potato Famine highlights genetic vulnerability of single-variety dependence

- Present: Global cultivation of diverse species with renewed interest in Andean native varieties

According to research published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, this evolutionary timeline demonstrates how human selection pressure created specialized species. The famine's devastation resulted from reliance on a single S. tuberosum variety vulnerable to late blight, underscoring why maintaining diverse potato species matters for food security. Modern agricultural scientists now actively preserve over 4,000 native Andean varieties through initiatives like the International Potato Center's gene bank in Lima, Peru.

Culinary Applications by Species and Variety

While all potato species are edible, their starch content, moisture levels, and texture determine optimal culinary uses. Understanding these differences prevents cooking disasters and elevates your dishes:

Starchy Potatoes (High Starch, Low Moisture)

Primary Species: Solanum tuberosum (russet varieties)

Best For: Baking, mashing, frying

Why: High starch content creates fluffy texture when cooked. Russets like Russet Burbank break down easily, making them ideal for light mashed potatoes or crispy french fries. These varieties contain 20-22% starch compared to 16-18% in waxy types.

Waxy Potatoes (Low Starch, High Moisture)

Primary Species: Solanum tuberosum (red, fingerling, new potatoes)

Best For: Boiling, roasting, salads

Why: Their firm texture holds shape during cooking. Varieties like Red Bliss maintain integrity in potato salad, while fingerlings develop delicious caramelization when roasted. These typically contain 16-18% starch with higher sugar content.

Specialty Andean Species

Primary Species: Solanum ajanhuiri, S. juzepczukii

Best For: Traditional Andean preparations, high-altitude growing

Why: These cold-tolerant species contain unique anthocyanins and glycoalkaloids that provide frost resistance but require proper preparation. In Peru, S. juzepczukii is traditionally made into chuño (freeze-dried potatoes) through a process documented by FAO as critical for food security in mountainous regions.

Practical Selection Guide for Home Cooks and Gardeners

Choosing the right potato isn't just about recipe requirements—it's about understanding the biological characteristics that determine performance:

For Perfect Mashed Potatoes

Reach for russet varieties (S. tuberosum group) with their high starch content. Yukon Golds offer a middle ground with buttery flavor and moderate starch. Avoid waxy potatoes which become gummy when mashed. For the fluffiest results, start potatoes in cold water and cook until just tender—overcooking releases too much starch.

For Salad That Holds Together

Select waxy varieties like French Fingerlings or Red Norlands. Their lower starch content (16-18%) and higher moisture prevent disintegration. Cook until just tender, then cool completely before dressing. New potatoes harvested in early summer offer exceptional flavor and texture for salads.

For High-Altitude Gardening

If you garden above 8,000 feet, consider heritage Andean species. According to USDA Agricultural Research Service trials, S. ajanhuiri demonstrates superior frost tolerance compared to standard S. tuberosum varieties. These species have adapted to short growing seasons and intense sunlight through millennia of natural selection.

Preserving Potato Diversity: Why It Matters

Modern agriculture relies heavily on just a few S. tuberosum varieties, creating vulnerability to disease outbreaks. The Irish Potato Famine demonstrated this risk when Phytophthora infestans (late blight) devastated Ireland's potato crop in the 1840s. Today, scientists at the International Potato Center maintain over 7,000 accessions representing diverse species and varieties.

These preservation efforts aren't just academic—they provide genetic resources for developing disease-resistant varieties. For example, researchers recently identified blight resistance genes in S. bulbocastanum (a wild species) that have been bred into commercial varieties. Climate change makes this work increasingly urgent, as rising temperatures threaten traditional potato-growing regions.

How to Incorporate Diverse Potatoes in Your Kitchen

Exploring beyond standard grocery store varieties opens new culinary possibilities:

- Visit farmers markets: Seek out heirloom varieties like Purple Peruvian (S. tuberosum tuberosum group) which maintains its vibrant color when cooked

- Try international varieties: Japanese inca purple or German laura offer unique flavor profiles

- Grow your own: Experiment with heritage seeds from organizations like Seed Savers Exchange

- Adjust cooking times: Different species require varied cooking durations—test for doneness rather than following strict timers

Remember that proper storage significantly impacts potato quality. Keep tubers in a cool, dark place with good ventilation—never refrigerate, as cold temperatures convert starch to sugar. Use paper bags rather than plastic to prevent moisture buildup and sprouting.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4