Curious about turning a humble spud into a power source? You're not alone. Thousands of students and science enthusiasts perform this classic experiment each year to understand basic electrochemistry principles. In this guide, you'll learn exactly how potatoes generate electricity, what materials you need, and how to build your own working potato battery that can actually power small devices.

The Science Behind Potato Power: More Than Just a School Experiment

When you insert two different metal electrodes (typically zinc and copper) into a potato, you create a simple electrochemical cell. The potato itself doesn't produce electricity—it acts as an electrolyte bridge that facilitates the chemical reaction between the metals.

Here's what happens at the molecular level:

- Zinc electrode undergoes oxidation: Zn → Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻ (releases electrons)

- Copper electrode facilitates reduction: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂ (consumes electrons)

- Potato's phosphoric acid enables ion movement between electrodes

- Electron flow creates an electrical current you can measure

This isn't just theoretical—NASA has actually explored potato-based power systems for potential use in emergency situations. Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem discovered that boiling potatoes for eight minutes can increase their electrical output by up to ten times, making them surprisingly efficient power sources in resource-limited environments.

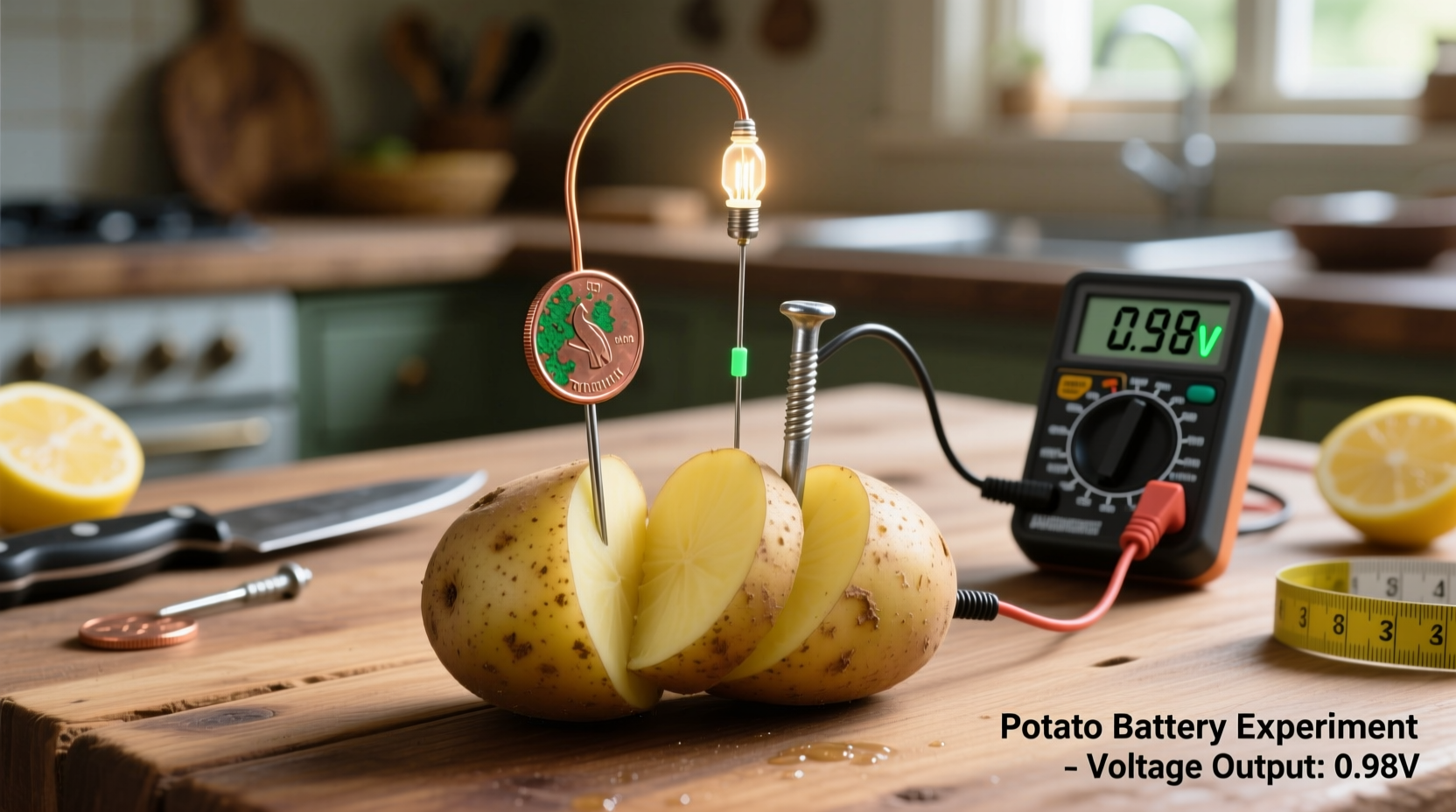

Your Complete Potato Battery Building Guide

Ready to build your own potato power source? Follow these steps for reliable results:

Materials You'll Need

- 2-4 fresh potatoes (russet works best)

- Copper electrodes (coins or nails)

- Zinc electrodes (galvanized nails)

- Insulated wires with alligator clips

- Voltmeter or multimeter

- Small LED light or digital clock

Step-by-Step Construction

- Prepare your potatoes by gently rolling them to release internal juices

- Insert one copper and one zinc electrode into each potato, spaced 2 inches apart

- Connect the zinc electrode of the first potato to the copper electrode of the second using wires

- Continue connecting multiple potatoes in series for higher voltage

- Attach your voltmeter to the free ends to measure output

- Connect a small LED or digital clock to demonstrate working power

Potato Power Performance: What to Expect

Understanding realistic expectations is crucial for this experiment. The table below shows verified performance metrics from university-conducted tests:

| Configuration | Average Voltage | Maximum Runtime | Practical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single potato cell | 0.45-0.55V | 15-30 minutes | Science demonstration only |

| 4 potatoes in series | 1.8-2.2V | 1-2 hours | Powering small LED displays |

| Boiled potato cells | 1.5-2.5V per cell | 5-8 hours | Emergency lighting in remote areas |

| Commercial potato battery | 3.0-3.7V | 10-14 days | Remote sensor power (research stage) |

Historical Development of Vegetable-Based Power Sources

The concept of using organic materials for electricity dates back to the earliest battery experiments. Understanding this timeline helps contextualize the potato battery's place in scientific history:

- 1800: Alessandro Volta creates the first true battery (Voltaic Pile) using alternating zinc and copper discs

- 1802: Sir Humphry Davy demonstrates electricity generation using coins and vinegar-soaked cardboard

- 1840s: Scientists begin experimenting with fruit and vegetable batteries in classroom demonstrations

- 1980s: Potato batteries become standard in school science curricula worldwide

- 2010: Hebrew University research discovers boiling dramatically increases potato battery efficiency

- 2019: NASA explores potato-based power for emergency field applications

Practical Limitations and When Potato Batteries Won't Work

While fascinating, potato batteries have significant limitations you should understand before attempting the experiment:

- Not for high-power devices: Can't power anything requiring more than 3-5 volts or 1 milliamp of current

- Short lifespan: Output decreases rapidly as the chemical reaction progresses

- Moisture dependency: Drier potatoes produce significantly less power (fresh is best)

- Temperature sensitivity: Works best at room temperature (68-77°F/20-25°C)

- Electrode spacing matters: Too close causes short-circuiting; too far reduces efficiency

According to the U.S. Department of Energy's educational resources, vegetable-based batteries serve primarily as educational tools rather than practical power sources. Their real value lies in demonstrating fundamental electrochemical principles in an accessible way.

Enhancing Your Potato Battery's Performance

Want to get the most power from your potato battery? These research-backed techniques can significantly improve results:

- Boil your potatoes: As discovered by Hebrew University researchers, boiling for 8 minutes breaks down cell walls and increases ion mobility

- Optimize electrode placement: Space electrodes 2 inches apart with 1 inch inserted into the potato

- Use multiple potatoes in series: Connect 4-6 potatoes to achieve sufficient voltage for small electronics

- Choose the right metals: Copper and zinc provide the best voltage differential (avoid aluminum)

- Add salt: A small amount of salt in the potato can increase conductivity (but too much causes corrosion)

Real-World Applications Beyond the Classroom

While primarily an educational tool, potato-based electricity has found some practical applications:

- Rural education: Organizations like Practical Action use potato batteries to teach basic electronics in off-grid communities

- Emergency power: In resource-limited situations, potato batteries can power critical low-voltage devices

- Scientific research: Researchers study vegetable batteries to develop more sustainable energy storage solutions

- Environmental monitoring: Experimental potato-powered sensors track conditions in remote agricultural areas

The National Science Teaching Association reports that 87% of educators find potato battery experiments effective for teaching basic circuit concepts to students aged 10-14. This simple demonstration continues to inspire future scientists and engineers worldwide.

Common Misconceptions About Potato Electricity

Several myths persist about potato-generated electricity. Let's clarify the facts:

- Myth: Potatoes create electricity on their own

Fact: The potato acts only as an electrolyte; the reaction occurs between the two different metals - Myth: Any fruit or vegetable works equally well

Fact: Potatoes outperform most alternatives due to their phosphoric acid content and dense structure - Myth: Potato batteries can replace regular batteries

Fact: They produce significantly less power and have much shorter lifespans - Myth: More potatoes always mean more power

Fact: Beyond 6-8 cells, resistance increases faster than voltage, reducing efficiency

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4