Contrary to common belief, potatoes don't have true roots where the edible part grows. The potato itself is a tuber—a specialized underground stem—not a root. Understanding this distinction is crucial for successful cultivation, as potato tubers develop from stolons (horizontal stems), while the actual root system absorbs water and nutrients.

Many gardeners and cooking enthusiasts search for "potato roots" expecting information about the edible portion, but this reflects a widespread botanical misunderstanding. Let's clarify potato plant anatomy once and for all, with practical insights that will transform your gardening approach and deepen your appreciation for this global staple food.

Why Potatoes Aren't Roots: Clearing Up the Confusion

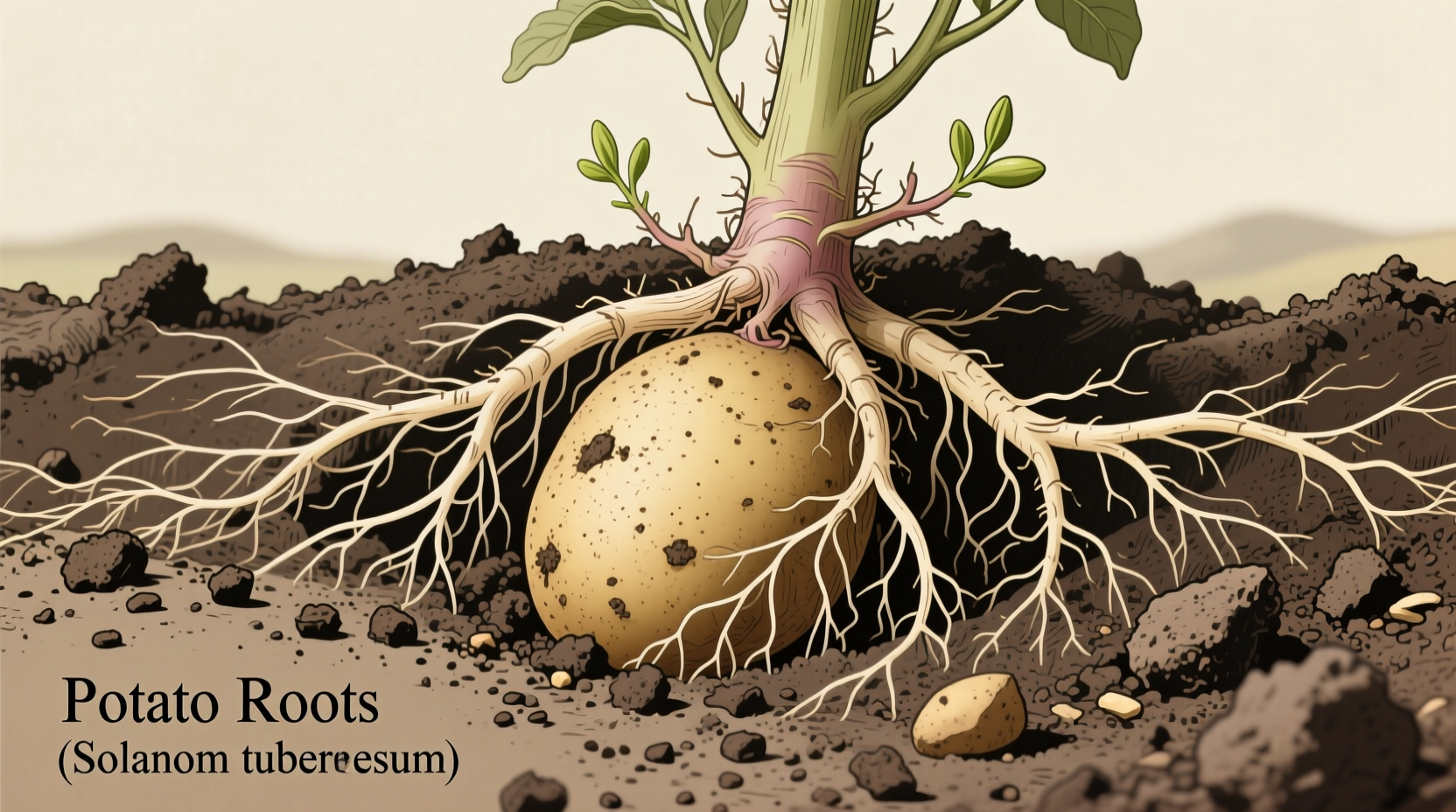

When you dig up a potato plant, what you're harvesting isn't a root vegetable like carrots or beets. Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) are tubers—swollen underground stems that store energy for the plant. This fundamental distinction affects everything from planting techniques to storage practices.

The confusion stems from how we categorize vegetables in everyday language versus botanical classification. While carrots, radishes, and turnips are true roots (modified taproots), potatoes belong to a different botanical category entirely. This isn't just academic—it directly impacts how you should grow and care for your potato plants.

Inside the Potato Plant: Anatomy Breakdown

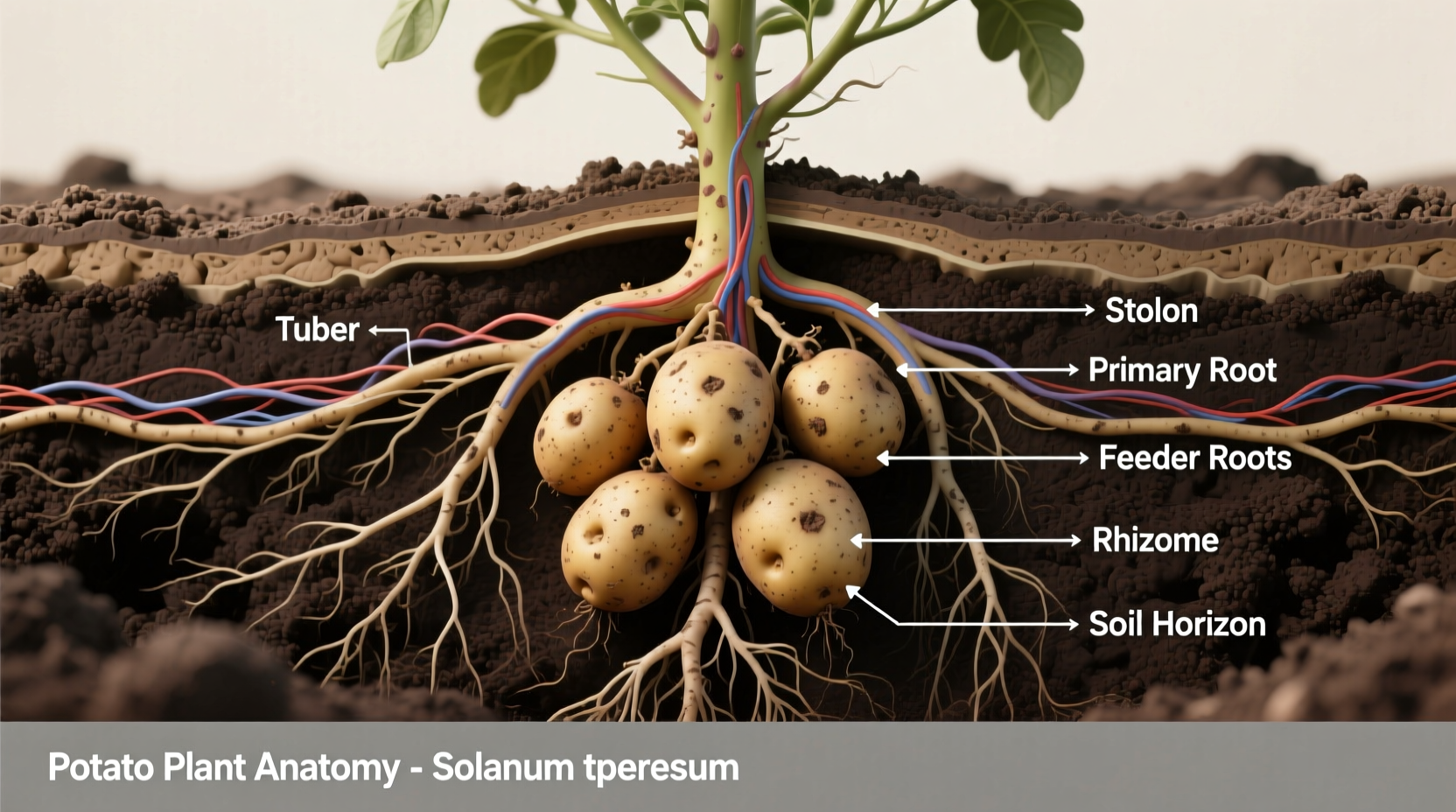

Understanding the complete underground structure of potato plants reveals why proper terminology matters:

- True root system: Fibrous, thread-like structures that absorb water and nutrients from soil

- Stolons: Horizontal underground stems that grow from the base of the plant

- Tubers: The swollen ends of stolons that develop into potatoes (storage organs with "eyes")

- Rhizomes: In some varieties, horizontal stems that produce new plants

This distinction explains why planting seed potatoes (cut pieces with eyes) works—they're planting stem tissue, not root tissue. True root vegetables like carrots can't be propagated this way.

Potato Development Timeline: From Planting to Harvest

Understanding the growth stages helps optimize your cultivation practices. Here's the typical development process for potato tubers:

| Weeks After Planting | Development Stage | Gardening Implications |

|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | Root establishment and sprout emergence | Keep soil consistently moist; avoid hilling yet |

| 4-6 | Stolon formation begins | First hilling to encourage stolon growth |

| 7-9 | Tuber initiation ("tuberization") | Maintain even moisture; avoid temperature extremes |

| 10-12 | Tuber bulking phase | Consistent watering critical; monitor for pests |

| 13-16+ | Tuber maturation | Reduce watering; wait for foliage to die back before harvest |

This timeline varies by potato variety and growing conditions. Early varieties mature in 70-90 days, while late-season types may take 120+ days. The critical tuber initiation phase (weeks 7-9) is particularly sensitive to environmental stressors like temperature fluctuations and inconsistent moisture.

Practical Gardening Implications: Why Anatomy Matters

Understanding that potatoes are tubers, not roots, directly impacts your gardening success:

Proper Planting Depth and Technique

Plant seed pieces 3-4 inches deep with eyes facing up. As plants grow to 6-8 inches tall, hill soil around the base to:

- Encourage more stolon development (more potential tubers)

- Prevent sunlight exposure that causes greening (solanine production)

- Provide loose soil for tuber expansion

Watering Strategies for Optimal Tuber Development

During tuber initiation and bulking phases, maintain consistent soil moisture. Fluctuations cause:

- Cracked tubers (from sudden heavy watering after dry periods)

- Hollow heart (internal cavities from rapid growth)

- Russeting (rough skin development)

According to the USDA Agricultural Research Service, potato plants require 1-2 inches of water weekly during tuber formation, with even moisture being more critical than total quantity.

Tubers vs. True Roots: Key Differences

Understanding these distinctions helps prevent common gardening mistakes:

| Characteristic | True Roots (Carrots, Beets) | Potato Tubers |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical classification | Modified taproot | Modified underground stem |

| Propagation method | From seed only | From "seed potatoes" (tuber pieces with eyes) |

| Storage organs | Root tissue stores energy | Stem tissue stores energy |

| "Eyes" or buds | None | Present (grow into new plants) |

| Response to light exposure | Generally unaffected | Turns green and produces toxic solanine |

Common Potato Growing Challenges Related to Anatomy

Many gardeners encounter problems that stem from misunderstanding potato plant structure:

Greening of Tubers

When tubers are exposed to light, they produce chlorophyll (green color) and solanine (a toxic compound). This happens because tubers are stem tissue, not root tissue. Proper hilling prevents this issue.

Poor Tuber Formation

Several factors can inhibit tuber development:

- Excessive nitrogen fertilizer (promotes leafy growth over tuber formation)

- High temperatures during tuber initiation (above 80°F/27°C)

- Inconsistent watering during critical growth phases

- Planting too shallow, causing tubers to form near the surface

Research from Cornell University's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences shows that maintaining soil temperatures below 70°F (21°C) during tuber initiation significantly improves yield and quality.

Practical Tips for Successful Potato Cultivation

Apply this anatomical knowledge to improve your harvest:

Soil Preparation Essentials

Prepare loose, well-draining soil with plenty of organic matter. Potatoes need room to expand—compacted soil produces misshapen tubers. The ideal pH range is 5.0-6.0, which also helps prevent common diseases like scab.

Optimal Hilling Technique

When plants reach 6-8 inches tall, mound soil around the base to cover all but the top few leaves. Repeat every 2-3 weeks until the hill reaches 8-12 inches high. This encourages more stolons to develop, increasing your potential harvest.

Harvest Timing Guidance

For new potatoes: Harvest 7-8 weeks after planting, when plants flower For main crop: Wait until foliage yellows and dies back completely Gently dig with a fork to avoid piercing tubers

Preserving Your Harvest: Storage Science

Understanding that potatoes are living tubers explains proper storage:

- Store at 45-50°F (7-10°C) with high humidity (85-90%)

- Keep in complete darkness to prevent greening

- Avoid storing with apples (ethylene gas promotes sprouting)

- Don't refrigerate (cold temperatures convert starch to sugar)

According to the University of Idaho's Potato Extension program, proper storage conditions can maintain potato quality for 6-8 months for most varieties.

Do potatoes grow on roots or stems?

Potatoes grow on specialized underground stems called stolons, not on roots. The potato itself is a tuber—a modified stem that stores energy for the plant. The actual root system is fibrous and separate, absorbing water and nutrients from the soil.

Why do people mistakenly call potatoes roots?

People often mistakenly call potatoes roots because they grow underground like carrots and beets. However, botanically, potatoes are stem tubers. This confusion persists because culinary classification (root vegetables) differs from botanical classification.

Can you plant a whole potato?

Yes, you can plant a whole small potato (often called a "seed potato"). Larger potatoes should be cut into pieces with at least one "eye" (growth bud) per piece, then allowed to cure for 24-48 hours before planting to prevent rotting.

How deep do potato roots grow?

The fibrous root system of potato plants typically grows 12-18 inches deep, while the tubers develop in the top 6-10 inches of soil. Proper hilling encourages more tubers to form higher in the soil profile where conditions are optimal.

What causes potatoes to turn green?

Potatoes turn green when tubers are exposed to light, triggering chlorophyll production. Since potatoes are stem tissue (not root tissue), they respond to light exposure by producing both chlorophyll and solanine, a toxic compound. Proper hilling prevents this issue.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4