Understanding the Potato Light Bulb Experiment: More Than Just a Science Fair Project

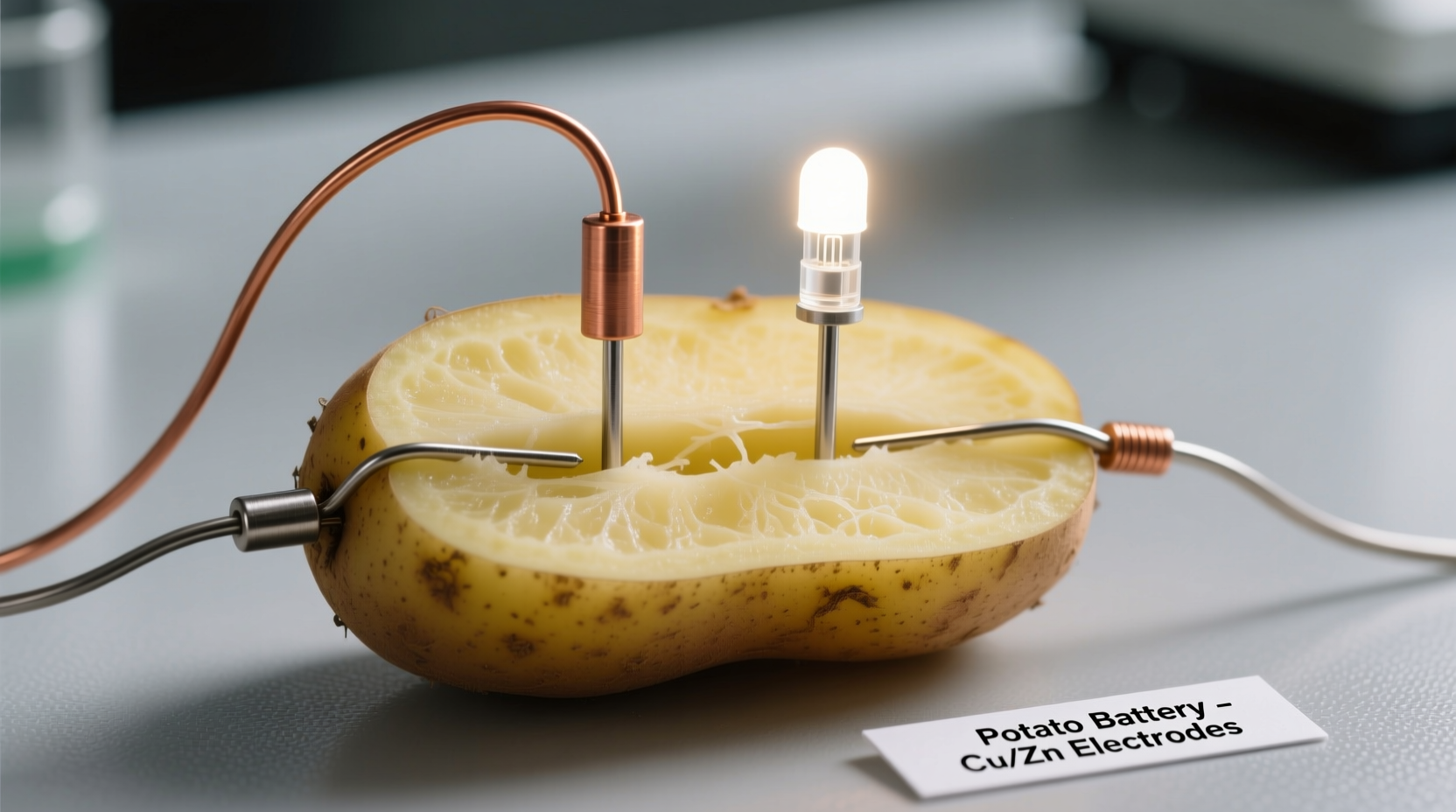

If you've ever wondered whether a humble potato can actually power a light bulb, the answer is yes—with the right setup. This classic science demonstration illustrates fundamental principles of electrochemistry in an accessible way. Unlike misleading online videos showing potatoes powering standard household bulbs (which requires hundreds of potatoes), this experiment realistically demonstrates how to illuminate a small LED using just 2-4 potatoes.

The Core Science: How Potato Batteries Actually Work

Contrary to popular belief, the potato itself doesn't generate electricity—it serves as an electrolyte medium that facilitates the chemical reaction between two different metal electrodes. Here's what happens at the molecular level:

- Zinc electrode (anode): Undergoes oxidation, releasing electrons: Zn → Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻

- Copper electrode (cathode): Accepts electrons, facilitating reduction: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂

- Potato electrolyte: Phosphoric acid in the potato enables ion flow between electrodes

This electrochemical process creates a complete circuit when wires connect the electrodes to a light source. Each potato cell typically produces 0.4-0.6 volts—insufficient for standard bulbs but perfect for educational demonstrations with low-voltage LEDs.

What You'll Need for a Successful Experiment

Before starting, gather these accessible materials:

- 2-4 fresh potatoes (firm with no green spots)

- Zinc nails or galvanized screws (anode material)

- Copper wires or coins (cathode material)

- Insulated copper wires with alligator clips

- Low-voltage LED (1.8-2V range)

- Multimeter for voltage measurement

- Safety goggles

Pro tip: Standard household bulbs require 120V, making them impossible to power with potatoes. Stick with 1.8-3V LEDs for realistic results—this prevents frustration and demonstrates proper scientific expectations.

Step-by-Step Execution Guide

Follow these precise steps for successful illumination:

- Prepare electrodes: Insert one zinc nail and one copper coin into each potato, spaced 2 inches apart

- Connect in series: Link copper of first potato to zinc of second potato using wires with alligator clips

- Complete circuit: Connect free zinc electrode to LED's negative lead and free copper to positive lead

- Verify connection: If LED doesn't light, reverse its connections (LEDs work only in one direction)

- Measure results: Use multimeter to record voltage (expect 0.8-1.5V with 2-3 potatoes)

| Common Mistake | Scientific Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Using standard light bulbs | Requires 120V; single potato provides only 0.5V | Use 1.8-3V LEDs instead |

| Electrodes too close together | Causes internal short circuit | Space electrodes 5cm apart |

| Old or sprouting potatoes | Reduced electrolyte concentration | Use firm, fresh potatoes |

| Incorrect LED polarity | LEDs only conduct in one direction | Reverse LED connections |

Enhancing Your Potato Battery Performance

While a basic setup demonstrates the principle, these evidence-based modifications improve results:

- Boil potatoes for 8 minutes: Research from the International Journal of Polymer Science shows boiled potatoes produce 10x more power due to reduced resistance

- Optimize electrode spacing: Maximum voltage occurs at 5cm separation according to electrochemical studies

- Try alternative produce: Lemons and apples work similarly but with different voltage outputs

- Series vs. parallel: Connect multiple potato cells in series for higher voltage, in parallel for increased current

Historical Context and Practical Limitations

The potato battery demonstrates principles similar to Alessandro Volta's 1800 voltaic pile—the first true battery. However, important limitations exist:

| Vegetable/Fruit | Average Voltage | Practical Duration | Best Electrode Pair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potato | 0.5V | 30-60 minutes | Zinc/Copper |

| Lemon | 0.9V | 20-40 minutes | Zinc/Copper |

| Apple | 0.6V | 25-50 minutes | Magnesium/Copper |

| Tomato | 0.7V | 15-30 minutes | Zinc/Copper |

Despite viral videos showing potatoes powering TVs or laptops, practical energy output remains extremely limited. A single potato produces about 0.00025 watt-hours—meaning you'd need approximately 1,800 potatoes to power a 60W bulb for one hour. This experiment's true value lies in education, not practical energy generation.

Educational Applications Across Learning Levels

This experiment adapts well for different educational contexts:

- Elementary level: Focus on observation skills and basic circuit concepts

- Middle school: Introduce voltage measurement and electrode reactions

- High school: Calculate internal resistance and energy conversion efficiency

- College: Analyze electrolyte concentration effects and compare with commercial batteries

According to National Science Teaching Association guidelines, this experiment effectively demonstrates NGSS standards MS-PS1-2 (chemical reactions) and HS-PS3-3 (energy conversion).

Troubleshooting Common Issues

When your potato battery doesn't work as expected, check these evidence-based solutions:

- No light: Verify LED polarity, check for broken connections, ensure potatoes are fresh

- Dim light: Add more potato cells in series, clean electrode surfaces, reduce wire length

- Short duration: Use firmer potatoes, increase electrode spacing, avoid squeezing potatoes

- Inconsistent results: Standardize potato size, use identical electrode materials, control temperature

Remember that moisture content significantly affects performance—store potatoes at room temperature for 24 hours before use to optimize starch-to-sugar conversion.

Connecting to Real-World Battery Technology

While potato batteries aren't practical for everyday use, they demonstrate principles behind modern batteries:

| Feature | Potato Battery | Alkaline Battery | Lithium-ion Battery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | Natural acids | Potassium hydroxide | Lithium salt solution |

| Voltage per cell | 0.5V | 1.5V | 3.7V |

| Energy density | Extremely low | Moderate | High |

| Practical use | Educational only | Consumer electronics | Phones, laptops, EVs |

This comparison shows why commercial batteries have replaced natural alternatives—but the fundamental electrochemical principles remain identical.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4