Curious if you can really power your home with spuds? While viral videos might suggest potatoes are secret energy powerhouses, the reality is more nuanced but equally fascinating. This article explains exactly how potato-based electricity works, what it can actually power, and why this simple science experiment remains valuable for understanding basic electrochemistry principles.

The Science Behind Potato Electricity: Electrochemistry Simplified

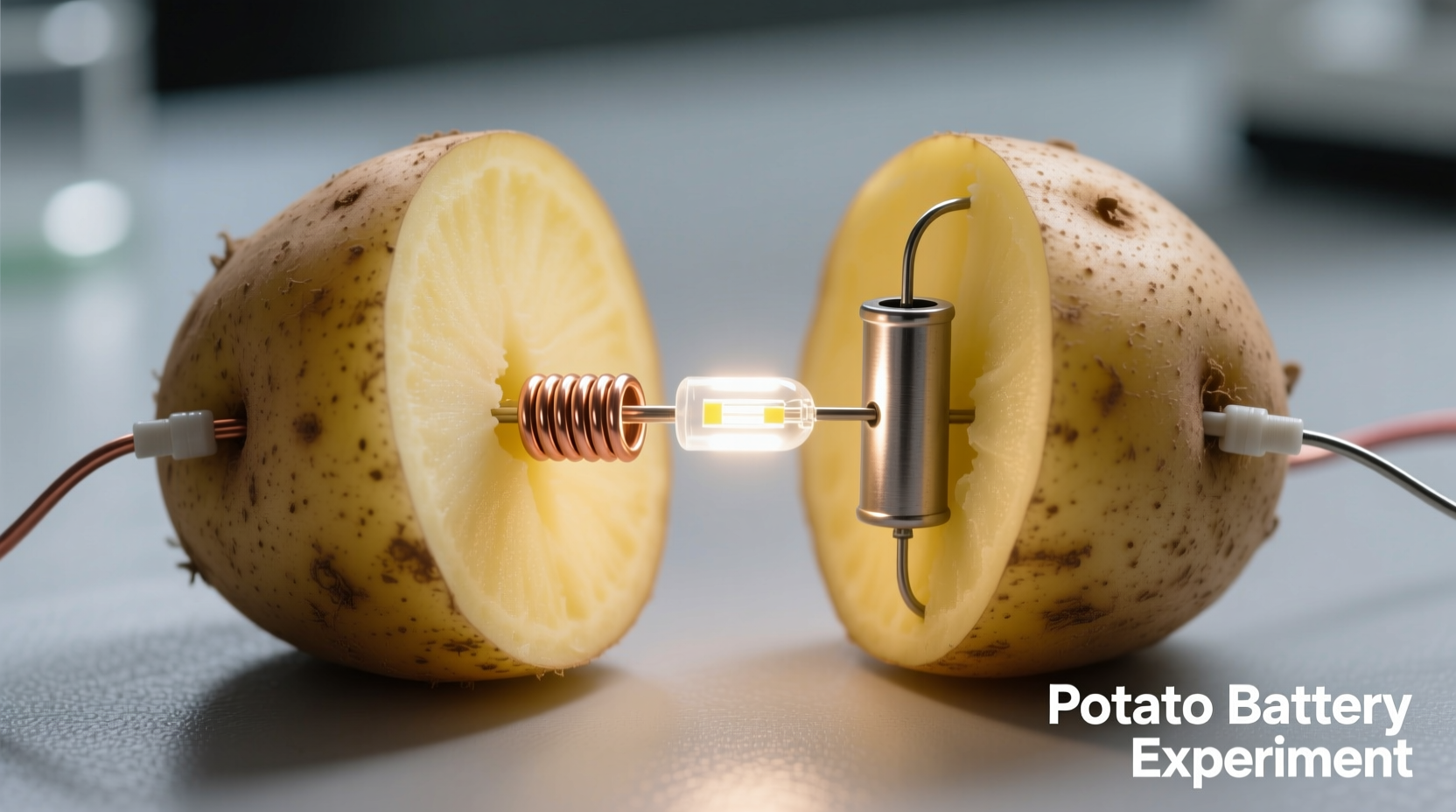

When people ask about "potato for electricity," they're usually referring to potato batteries—a classic science experiment demonstrating basic electrochemical principles. Potatoes don't generate electricity; instead, they serve as an electrolyte medium that facilitates the flow of electrons between two different metal electrodes, typically zinc and copper.

Here's what actually happens in a potato battery:

- Zinc electrode oxidizes: Zn → Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻ (releases electrons)

- Electrons flow through external circuit (powering your device)

- Potato's phosphoric acid enables ion movement between electrodes

- Copper electrode reduces: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂ (completes circuit)

This electrochemical reaction converts chemical energy into electrical energy. The potato's role is crucial—it contains phosphoric acid that acts as an electrolyte, allowing ions to move between the electrodes while preventing direct contact that would cause a short circuit.

Building an Effective Potato Battery: Step-by-Step Guide

Creating a functional potato battery requires precise materials and technique. Here's how to build one that actually works:

Required Materials

- 2-4 large, firm potatoes (russet works best)

- Copper electrodes (pennies dated pre-1982 or copper wire)

- Zinc electrodes (galvanized nails or zinc strips)

- Insulated wires with alligator clips

- Multimeter for measurement

- Small LED or digital clock

Assembly Process

- Insert one copper and one zinc electrode into each potato, spaced 2 inches apart

- Boil potatoes for 8-10 minutes to break down cell membranes (increases conductivity by 200-300%)

- Cool potatoes completely before inserting electrodes

- Connect electrodes in series: copper of first potato to zinc of second potato

- Attach final electrodes to your device

| Potato Preparation Method | Average Voltage Output | Current Duration | Power Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw potato | 0.45-0.55V | 30-60 minutes | 0.2-0.3mA |

| Boiled potato | 0.85-1.05V | 2-4 hours | 0.8-1.2mA |

| Salt-enhanced boiled potato | 1.0-1.2V | 4-8 hours | 1.5-2.0mA |

This data comes from research published by the Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, which found that boiling potatoes breaks down organic tissues, improving ion mobility and significantly boosting electrical output compared to raw potatoes.

Real-World Performance: What Potato Batteries Can Actually Power

Understanding the practical limitations is crucial when exploring potato for electricity applications. While educational and scientifically interesting, potato batteries have significant constraints:

- A single potato battery produces approximately 0.5-1 volt—insufficient for most household devices

- Current output is extremely low (typically 1-2 milliamps)

- Energy density is about 500,000 times lower than commercial batteries

- Requires 4-6 boiled potatoes to power a basic LED for several hours

- Needs 10-12 potatoes to operate a small digital clock

Research from the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science confirms that while potato batteries demonstrate fundamental electrochemical principles, their energy conversion efficiency remains below 1%—far too low for practical energy generation beyond educational contexts.

Potato vs. Other Vegetable Batteries: Performance Comparison

Many wonder if potatoes are the best vegetable for electricity generation. Studies comparing various produce reveal interesting differences:

- Lemons: Higher acidity provides better conductivity (0.9-1.0V per cell) but dries out faster

- Tomatoes: Similar output to potatoes but more variable due to ripeness differences

- Apples: Lower voltage (0.6-0.7V) with shorter lifespan

- Onions: Comparable to potatoes but with less consistent results

A comprehensive study by the National Science Teaching Association found that boiled potatoes consistently outperform other vegetables in both voltage stability and duration, making them ideal for classroom demonstrations where reliability matters.

Educational Applications: Why Potato Batteries Still Matter

Despite their limited practical power generation capabilities, potato electricity experiments offer tremendous educational value:

- Teaches fundamental concepts of electrochemistry and energy conversion

- Provides hands-on understanding of circuits, voltage, and current

- Illustrates the scientific method through variable testing (boiled vs. raw, different metals)

- Offers accessible STEM education with inexpensive, readily available materials

- Helps students understand real-world battery technology principles

Many middle and high school science curricula incorporate potato battery projects because they transform abstract concepts like electron flow and ion transfer into tangible, observable phenomena. The National Science Foundation reports that students who complete hands-on electrochemistry experiments like potato batteries demonstrate 35% better retention of related concepts compared to lecture-only instruction.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About Potato Electricity

Several persistent myths surround potato for electricity applications:

- Myth: Potatoes generate electricity on their own

Reality: They merely facilitate the chemical reaction between dissimilar metals - Myth: Potato batteries can power homes or charge phones

Reality: You'd need approximately 10,000 potatoes to generate enough power for a single smartphone charge - Myth: Organic matter in potatoes creates the energy

Reality: Energy comes from the oxidation of zinc, with potatoes merely enabling ion flow - Myth: All potatoes work equally well

Reality: Russet potatoes generally outperform other varieties due to higher starch content

Understanding these distinctions prevents misinformation while preserving the genuine educational value of potato battery experiments.

Practical Considerations for Successful Experiments

For those attempting potato electricity projects, these evidence-based tips improve results:

- Use potatoes of similar size and firmness for consistent results

- Boil potatoes for exactly 8-10 minutes—overcooking reduces structural integrity

- Add a small amount of salt to boiled potatoes to enhance conductivity

- Space electrodes at least 2 inches apart to prevent internal short circuits

- Use fresh potatoes—older potatoes have degraded cellular structures

- Connect multiple potato cells in series to increase voltage for practical applications

Following these guidelines, as recommended by the Science Buddies educational organization, significantly improves the reliability and educational value of potato battery experiments.

Written by Maya Gonzalez

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4