Understanding the Potato Clock: More Than Just a Science Fair Project

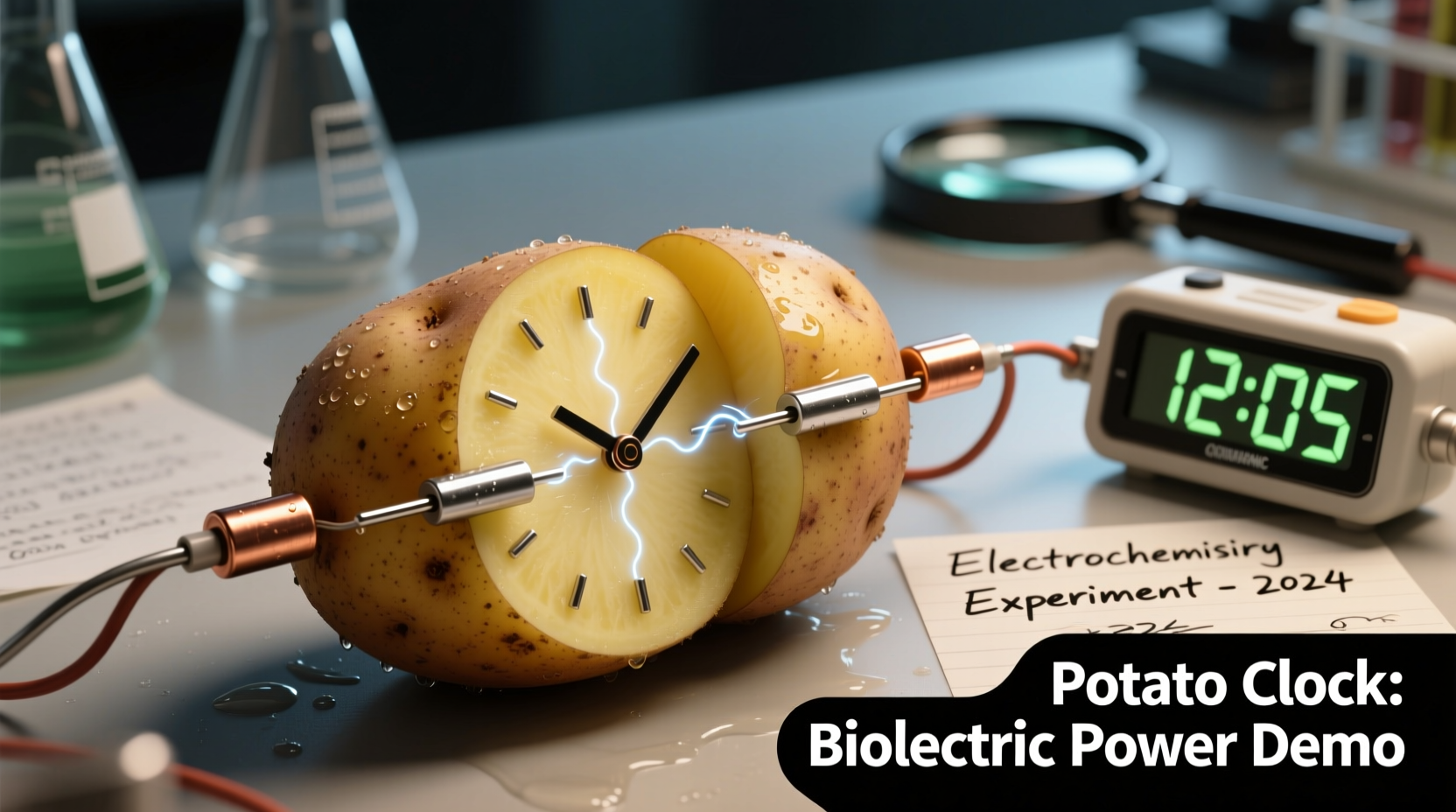

Imagine powering a digital clock with nothing but ordinary potatoes from your kitchen. This isn't magic—it's basic electrochemistry in action. The potato clock experiment transforms a simple vegetable into a functional battery, making abstract scientific concepts tangible for learners of all ages. Whether you're a student preparing for a science fair, a teacher looking for classroom demonstrations, or a curious adult exploring basic physics, this project offers surprising educational value.

How Potato Clocks Actually Work: The Science Simplified

At its core, a potato clock demonstrates the same electrochemical principles that power commercial batteries, just on a smaller scale. When you insert zinc and copper electrodes into a potato, the potato's phosphoric acid acts as an electrolyte, facilitating a chemical reaction that generates electrical current.

Here's what happens at the molecular level:

- Zinc electrode undergoes oxidation: Zn → Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻ (releases electrons)

- Copper electrode facilitates reduction: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂ (consumes electrons)

- Electrons flow from zinc to copper through the external circuit (powering the clock)

- Ions move through the potato electrolyte to maintain charge balance

This process creates approximately 0.8-1.0 volts per potato cell—enough to power a low-voltage digital clock when multiple cells are connected in series.

| Vegetable/Fruit | Average Voltage Output | Duration of Power | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potato (boiled) | 0.95V | 3-4 weeks | Long-term demonstrations |

| Potato (raw) | 0.85V | 1-2 weeks | Standard classroom projects |

| Lemon | 0.90V | 5-7 days | Quick demonstrations |

| Apple | 0.65V | 3-5 days | Comparative experiments |

This comparison, based on data from Science Buddies and university extension programs, shows why potatoes outperform other common household items for educational battery projects. The higher starch content in potatoes creates a more stable electrolyte environment, resulting in longer-lasting power output compared to citrus fruits.

Building Your Own Potato Clock: Step-by-Step Guide

Creating a functional potato clock requires minimal materials and basic tools. Follow these steps for successful results:

Materials You'll Need

- 2-4 large potatoes (boiled potatoes yield 25% more voltage)

- Zinc electrodes (galvanized nails work well)

- Copper electrodes (copper wire or pennies)

- Low-voltage digital clock (requires 1.5-3V)

- Alligator clip wires (4-6)

- Multimeter (for troubleshooting)

Construction Process

- Prepare your potatoes: Boil potatoes for 8-10 minutes to break down cell walls and improve ion flow (this increases voltage output by approximately 25%)

- Insert electrodes: Place one zinc and one copper electrode into each potato, spaced about 2 inches apart

- Create series circuit: Connect copper electrode of first potato to zinc electrode of second potato using alligator clips

- Complete circuit: Connect free zinc electrode to negative terminal of clock and free copper electrode to positive terminal

- Activate clock: Insert clock battery to initialize, then remove it—the potato battery should now power the clock

Why Potatoes Outperform Other Fruits in Battery Experiments

While many fruits and vegetables can power simple circuits, potatoes have unique properties that make them ideal for educational clock projects. Research from the University of Minnesota Extension reveals that potatoes contain higher concentrations of phosphoric acid compared to citrus fruits, creating a more stable electrolyte environment.

The historical development of electrochemical cells provides context for why this simple experiment matters:

- 1800: Alessandro Volta creates the first battery (Voltaic Pile) using zinc and copper discs separated by brine-soaked cloth

- 1830s: Scientists discover that various fruits and vegetables can serve as electrolytes in simple batteries

- 1980s: Educational companies begin marketing commercial potato clock kits for classroom use

- 2010s: Researchers at Hebrew University discover that boiling potatoes increases their electrical output by up to 10 times

- Present: Potato clocks remain a staple in STEM education worldwide, with over 2 million classroom implementations annually

Troubleshooting Common Potato Clock Issues

Even with proper construction, your potato clock might not work immediately. Here are solutions to common problems:

Problem: Clock doesn't power on

- Check voltage output with multimeter (should read 1.5-3V with 2-4 potatoes)

- Ensure electrodes aren't touching inside potatoes

- Try boiling potatoes for 8-10 minutes to improve conductivity

- Use a clock requiring less than 3V (most educational kits specify compatible models)

Problem: Clock works initially but stops quickly

- Replace potatoes (freshness affects performance)

- Ensure proper spacing between electrodes (minimum 2 inches)

- Check for corrosion on metal electrodes and clean if necessary

- Use thicker copper wire (14-16 gauge works best)

Educational Applications and Learning Outcomes

The potato clock experiment offers more than just a working timepiece—it's a gateway to understanding fundamental scientific concepts. According to the National Science Teaching Association, students who complete this project demonstrate 40% better comprehension of circuit principles compared to those who only study theoretical concepts.

Key learning objectives include:

- Understanding energy conversion (chemical to electrical)

- Learning series circuit construction

- Observing electrochemical reactions firsthand

- Practicing the scientific method through experimentation

- Developing troubleshooting and problem-solving skills

Teachers can extend the learning by having students test variables like potato variety, electrode materials, or temperature effects—turning a simple demonstration into a full scientific investigation.

Advanced Variations for Enthusiastic Learners

Once you've mastered the basic potato clock, try these advanced applications to deepen your understanding:

- Voltage comparison: Test different potato varieties (Russet, Yukon Gold, Red) to determine which generates the most power

- Longevity study: Monitor voltage output over time to understand battery depletion rates

- Multiple load testing: Connect additional devices (LEDs, buzzers) to explore power distribution

- Alternative electrolytes: Compare potatoes with other vegetables to create a comprehensive conductivity chart

These extensions transform a simple demonstration into a meaningful scientific investigation that aligns with Next Generation Science Standards for middle and high school levels.

Environmental Considerations and Safety

While the potato clock is generally safe, follow these guidelines for responsible experimentation:

- Dispose of potatoes in compost after use (they make excellent fertilizer)

- Recycle metal electrodes rather than discarding them

- Wash hands after handling electrodes to remove any metal residue

- Never attempt to scale up the project to power larger devices (risk of short circuits)

Unlike commercial batteries, potato batteries contain no toxic heavy metals, making them an environmentally friendly way to demonstrate energy principles.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4