Understanding Oxalates in Your Leafy Greens

When you reach for that vibrant bunch of spinach, you're grabbing one of nature's nutritional powerhouses—but it comes with a biochemical complexity worth understanding. Oxalates, naturally occurring compounds in many plants, have become a topic of interest for health-conscious eaters and those managing specific medical conditions. Let's cut through the confusion with evidence-based information you can actually use.

What Exactly Are Oxalates and Why Do They Matter?

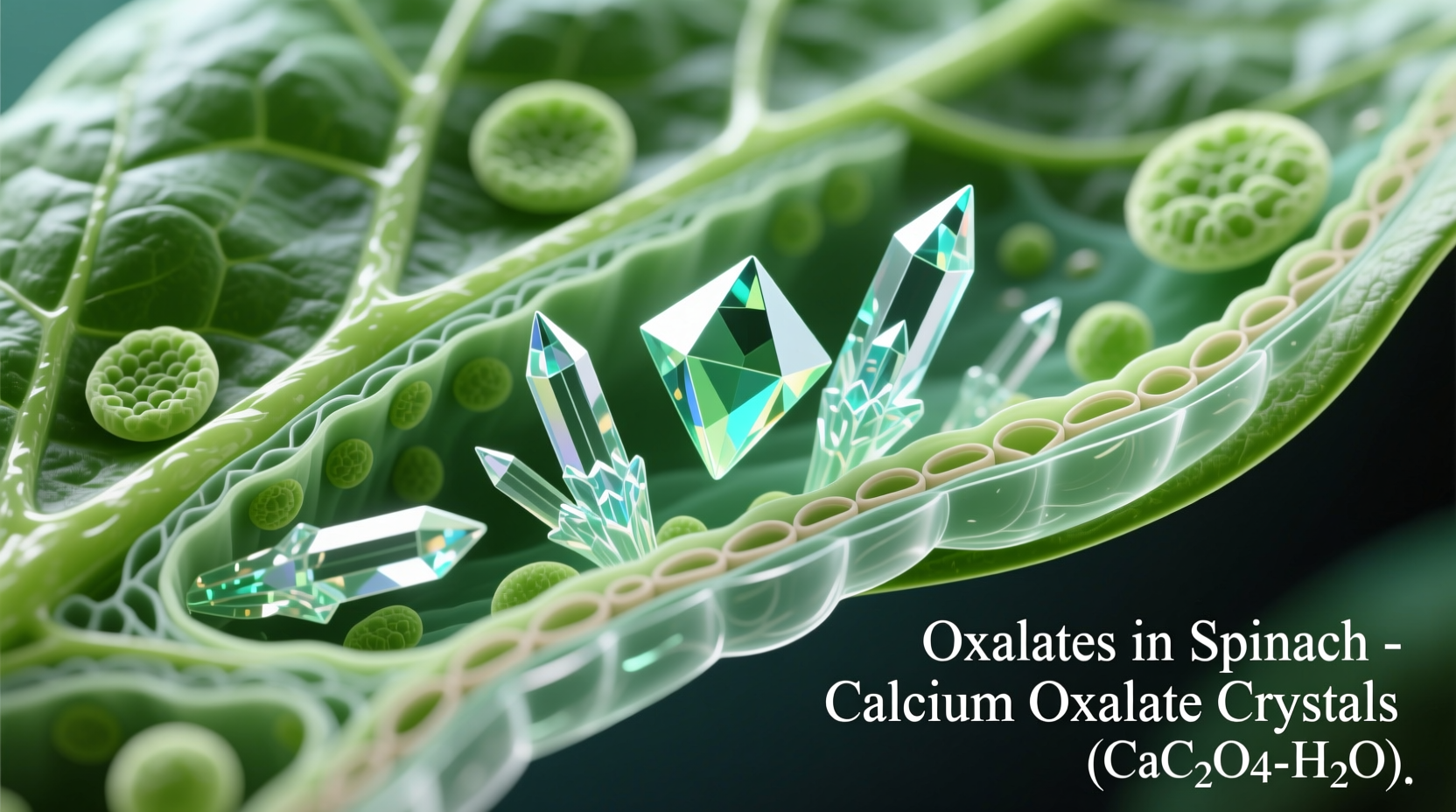

Oxalates (or oxalic acid) are naturally occurring organic compounds found in many plant foods. Plants produce them as part of their metabolic processes, serving functions like calcium regulation and defense against pests. In human nutrition, oxalates become relevant primarily because they can bind with minerals like calcium, potentially affecting absorption and, in susceptible individuals, contributing to kidney stone formation.

Contrary to popular belief, most oxalate in your body (about 80%) is produced internally rather than coming from food. Only 2-15% of dietary oxalate gets absorbed, with the rest being eliminated through stool. This biological context is crucial for understanding why spinach's oxalate content shouldn't automatically scare you away from this nutrient-dense food.

Spinach's Oxalate Content: Numbers That Matter

Let's get specific about what you're actually consuming. Spinach ranks among the highest oxalate-containing vegetables, but the exact amount varies based on preparation method:

| Preparation Method | Oxalate Content (per 100g) | Typical Serving Size | Total Oxalates per Serving |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw spinach | 750-800 mg | 30g (1 cup) | 225-240 mg |

| Boiled spinach, drained | 400-500 mg | 180g (1 cup cooked) | 720-900 mg |

| Steamed spinach | 600-700 mg | 180g (1 cup cooked) | 1080-1260 mg |

This fact comparison table from USDA FoodData Central and peer-reviewed research published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry reveals an important nuance: while boiling reduces oxalate concentration per gram, the typical serving size of cooked spinach is much larger, potentially resulting in higher total oxalate intake. This contextual detail often gets overlooked in simplified dietary advice.

Health Implications: Separating Fact From Fear

Here's where many discussions about oxalates go wrong—they present the information without appropriate context. Spinach remains an exceptional source of vitamins K, A, folate, magnesium, and antioxidants that support overall health. The nutritional benefits generally outweigh oxalate concerns for most people.

The primary health consideration involves kidney stone formation. Research from the National Kidney Foundation indicates that only about 8% of calcium oxalate stones (the most common type) come directly from dietary oxalate. For context, your body produces significantly more oxalate internally than you typically consume through food.

Context boundaries matter significantly: For healthy individuals without kidney stone history, spinach consumption poses minimal risk. The concern becomes more relevant for those with:

- Recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones

- Certain digestive disorders like inflammatory bowel disease

- History of enteric hyperoxaluria

Practical Strategies for Enjoying Spinach Safely

Whether you're a spinach enthusiast or need to moderate your intake, these evidence-based approaches can help you make informed choices:

Cooking Methods That Reduce Oxalates

Boiling proves most effective for oxalate reduction. A study in the Journal of Food Science demonstrated that boiling spinach for 10 minutes and discarding the water reduces soluble oxalate content by 30-50%. Steaming or sautéing shows minimal reduction, as the oxalates remain in the vegetable rather than leaching into cooking water.

Smart Pairing Techniques

Consuming calcium-rich foods simultaneously with high-oxalate foods can help bind oxalates in the digestive tract, reducing absorption. Try pairing spinach with:

- Plain Greek yogurt in smoothies

- Feta or goat cheese in salads

- Milk-based sauces for cooked spinach

Portion Guidance Based on Individual Needs

Rather than eliminating spinach entirely, consider these portion adjustments:

- General population: No restrictions needed—enjoy spinach freely as part of a balanced diet

- Occasional kidney stone formers: Limit raw spinach to 1 cup daily, cooked spinach to ½ cup daily

- Frequent kidney stone formers: Consult a registered dietitian for personalized guidance

Common Oxalate Myths Debunked

Let's address some persistent misconceptions clouding the oxalate conversation:

Myth: All oxalates are bad for you

Reality: Oxalates serve important functions in plant biology, and moderate amounts pose no risk to most people. Complete avoidance would eliminate many nutritious plant foods from your diet.

Myth: You should never eat raw spinach

Reality: Raw spinach provides higher levels of certain heat-sensitive nutrients like vitamin C. For most people, raw spinach consumption is perfectly appropriate.

Myth: Oxalates cause kidney stones in everyone

Reality: Only a small percentage of kidney stones come directly from dietary oxalate. Hydration status, overall diet pattern, and genetic factors play larger roles in stone formation.

When to Consult a Professional

If you have a history of calcium oxalate kidney stones or certain digestive conditions, work with a registered dietitian who specializes in renal nutrition. They can help you develop a personalized eating pattern that includes appropriate amounts of high-oxalate foods while ensuring you still receive essential nutrients. Remember that individual responses to dietary oxalate vary significantly based on gut health, genetics, and overall dietary pattern.

Final Thoughts on Spinach and Oxalates

The relationship between spinach and oxalates represents a perfect example of why nutrition advice needs personalization. For the vast majority of people, spinach remains an exceptionally healthy food worth including regularly in your diet. The key is understanding your individual health context and applying practical strategies when needed.

By focusing on evidence-based approaches rather than fear-driven restrictions, you can continue enjoying spinach's remarkable nutritional profile while managing any potential concerns intelligently. After all, dietary patterns—not single nutrients—determine long-term health outcomes.

Does cooking spinach reduce its oxalate content significantly?

Boiling spinach and discarding the water reduces soluble oxalate content by 30-50%, according to research in the Journal of Food Science. Steaming or sautéing shows minimal reduction as oxalates remain in the vegetable rather than leaching into cooking water.

How much spinach is safe to eat daily if I'm concerned about oxalates?

For most healthy individuals, 1-2 cups of raw spinach daily poses no risk. Those with kidney stone history should limit to 1 cup raw or ½ cup cooked spinach daily, while frequent stone formers should consult a dietitian for personalized guidance.

Can I still get the nutritional benefits of spinach while minimizing oxalate intake?

Yes, by boiling spinach and pairing it with calcium-rich foods like yogurt or cheese. This approach reduces oxalate absorption while preserving many nutrients. You can also rotate spinach with lower-oxalate greens like kale or romaine lettuce.

Are baby spinach leaves lower in oxalates than mature spinach?

Research shows minimal difference in oxalate content between baby and mature spinach. Both contain high levels of oxalates, though baby spinach may have slightly higher water content, resulting in marginally lower concentration per volume.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4