Discover the fascinating journey of one of the world's most beloved fruits—from its humble beginnings in the Andes to becoming a kitchen staple across continents. This comprehensive guide reveals not just where tomatoes originated, but how understanding their history can transform your gardening and cooking experiences.

The Scientific Roots: Identifying Tomato's True Ancestors

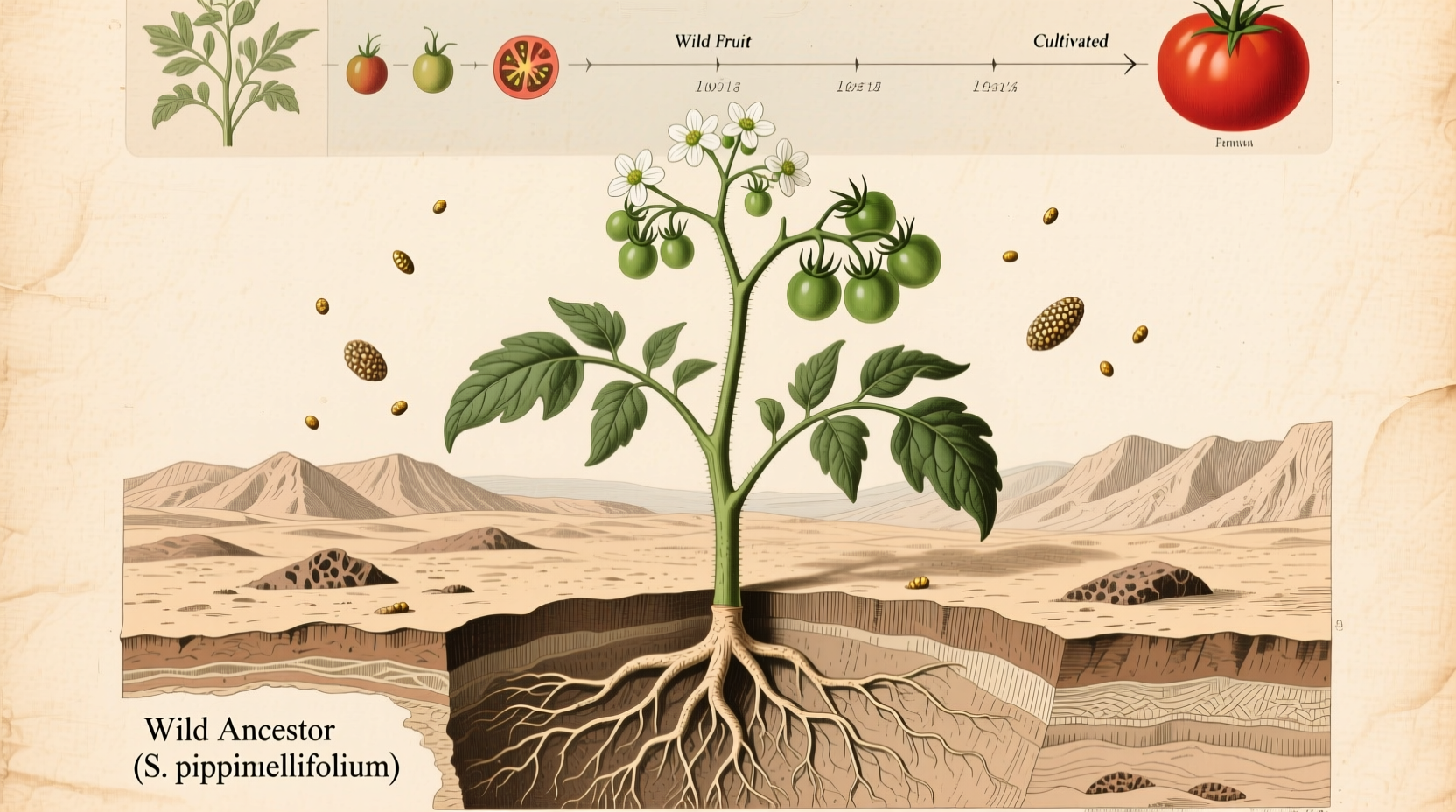

Botanists classify the cultivated tomato as Solanum lycopersicum, part of the nightshade family (Solanaceae) that includes potatoes and peppers. Genetic research confirms its closest wild relatives are small-fruited species like Solanum pimpinellifolium (the currant tomato), still found growing naturally in coastal Peru and Ecuador.

Unlike many domesticated crops, tomatoes underwent relatively recent cultivation—archaeological evidence from Tehuacán Valley in Mexico shows domestication began approximately 2,500 years ago. Early Mesoamerican civilizations like the Aztecs called the fruit xitomatl (meaning "plump thing with a navel") and incorporated it into their cuisine long before European contact.

Tomato Evolution Timeline: From Wild Specimens to Global Staple

| Time Period | Key Development | Geographical Spread |

|---|---|---|

| 7000-5000 BC | Wild tomato ancestors grow naturally in western South America | Peru, Ecuador, Chile |

| 500 BC | First evidence of cultivation in Mesoamerica | Mexico |

| 1521 | Spanish conquistadors bring tomatoes to Europe | Spain |

| 16th century | Spread throughout Europe, initially grown as ornamental plants | Italy, France, England |

| 18th century | Overcoming "poisonous" reputation, becoming culinary staple | Northern Europe, North America |

| 19th century | Commercial cultivation begins in United States | Global spread |

From Suspicion to Staple: The Tomato's Rocky Path to Acceptance

When Spanish explorers first brought tomatoes to Europe in the 16th century, they faced widespread suspicion. Many Europeans believed tomatoes were poisonous due to their membership in the nightshade family. Wealthy Europeans grew them as ornamental plants but avoided eating them for nearly 200 years.

The turning point came in Italy, where tomatoes gradually entered culinary tradition. By the late 17th century, Italian cookbooks began featuring tomato recipes. The fruit gained wider acceptance after French pharmacist Parmentier demonstrated its safety in the 1780s, and by the 19th century, tomatoes had become essential to Mediterranean cuisine.

Modern Varieties and Their Ancient Connections

Today's cultivated tomatoes have evolved significantly from their wild ancestors. While wild S. pimpinellifolium produces pea-sized fruits, selective breeding has created the diverse varieties we know today. Genetic studies by the USDA Agricultural Research Service show that just seven ancestral lines contributed to most modern tomato varieties.

Heirloom varieties like 'Andean Purple' and 'Peruvian Giant' maintain closer genetic ties to original South American specimens. These varieties often exhibit greater disease resistance and unique flavor profiles that commercial hybrids have lost through selective breeding for shelf life and uniform appearance.

Practical Applications: What Tomato Origins Mean for Gardeners

Understanding tomato origins provides valuable insights for modern cultivation:

- Climate considerations: Tomatoes thrive in warm conditions similar to their Andean homeland—65-85°F (18-29°C) with plenty of sunlight

- Soil preferences: They prefer slightly acidic soil (pH 6.2-6.8), mimicking the volcanic soils of their native region

- Disease resistance: Wild relatives contain genetic traits that modern breeders are reintroducing to combat common diseases

- Watering techniques: Mimic the seasonal rainfall patterns of their native habitat with deep, infrequent watering

Gardeners growing heirloom varieties often report richer flavors that reflect the complex taste profiles of early cultivated tomatoes, before commercial breeding prioritized uniformity and transportability over taste.

Preserving Tomato Heritage: Conservation Efforts

Organizations like the Tomato Genetics Resource Center at UC Davis and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) maintain extensive seed banks preserving wild tomato species and heirloom varieties. These collections serve as genetic reservoirs for future breeding efforts, particularly as climate change creates new agricultural challenges.

Home gardeners can contribute to preservation by growing heirloom varieties and saving seeds—a practice that connects modern cultivation with ancient traditions dating back to Mesoamerican farmers.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4