When you're cooking dinner or planning meals, understanding the relationship between potatoes and starch matters more than you might think. Whether you're managing blood sugar, perfecting your mashed potatoes, or exploring gluten-free alternatives, knowing exactly how potatoes function as a starchy food can transform your culinary results and nutritional choices.

What Exactly Is Starch, and Where Do Potatoes Fit In?

Starch is a complex carbohydrate made of long chains of glucose molecules. It serves as nature's energy storage system in plants. Potatoes, as tubers, store energy primarily as starch to fuel their growth when conditions improve.

Unlike purified starches like cornstarch or potato starch powder (which are 80-90% pure starch), whole potatoes contain starch granules embedded in a matrix of water, fiber, protein, and nutrients. This structural difference explains why eating a baked potato affects your body differently than consuming isolated starch.

| Food Item | Starch Content | Water Content | Key Nutrients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Potato | 15-20% | 79% | Vitamin C, Potassium, Fiber |

| Potato Starch Powder | 85-90% | 10-15% | Negligible |

| Cooked White Rice | 28-30% | 70% | B Vitamins, Iron |

| Cooked Sweet Potato | 20-25% | 75% | Vitamin A, Vitamin C |

This comparison from USDA FoodData Central shows why confusing whole potatoes with pure starch leads to nutritional misunderstandings. The water and fiber content in whole potatoes significantly affects how your body processes the starch.

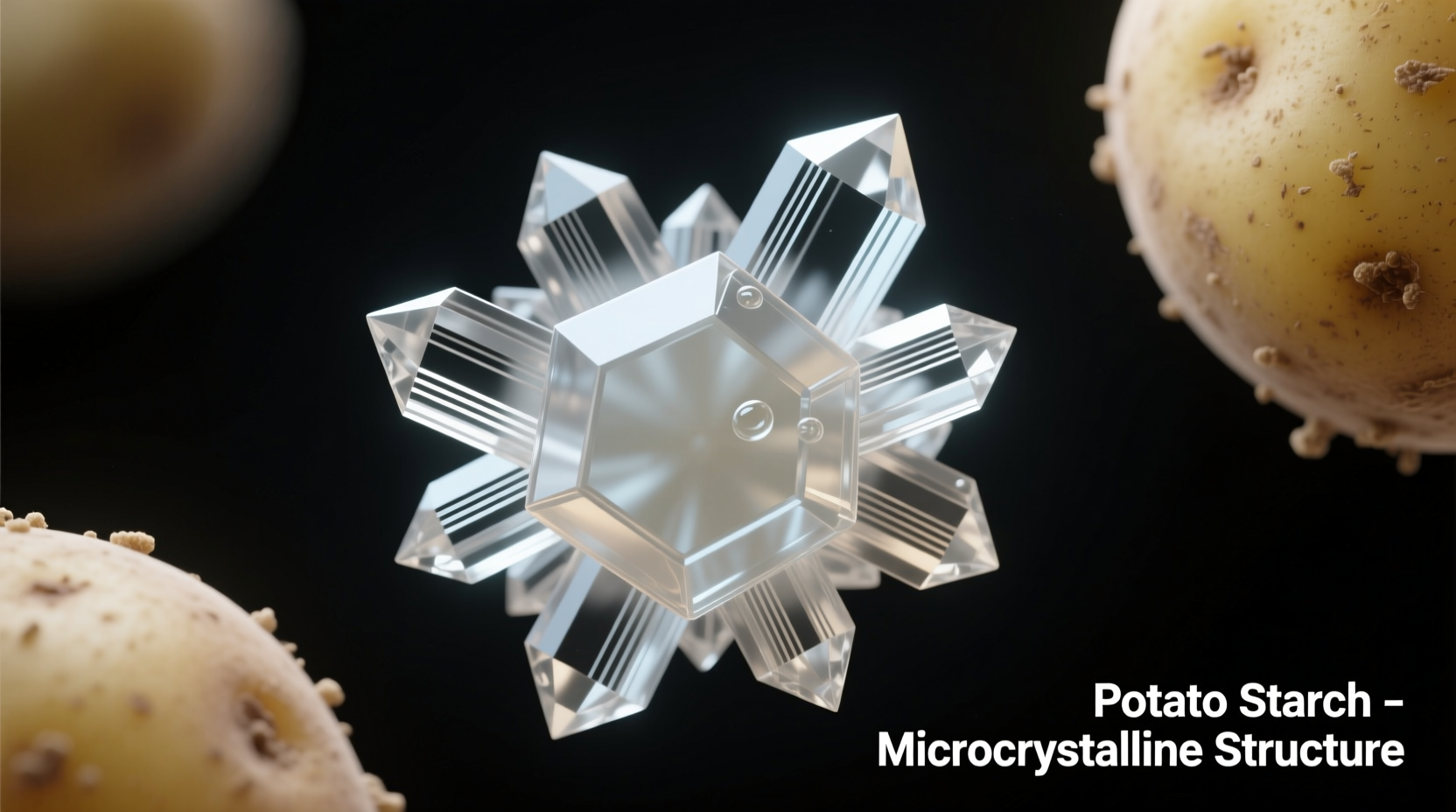

The Science Behind Potato Starch Composition

Potato starch consists of two molecular components: amylose (20-25%) and amylopectin (75-80%). This ratio gives potatoes their distinctive cooking properties compared to other starchy foods. When heated in water, potato starch granules swell dramatically—up to 10 times their original size—creating that familiar creamy texture in mashed potatoes.

According to research published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, the unique structure of potato starch makes it particularly effective for thickening sauces without developing a raw flour taste. This property explains why professional chefs often prefer potato starch over cornstarch for delicate sauces and pie fillings.

How Cooking Transforms Potato Starch

Your cooking method dramatically alters potato starch behavior. When you bake or boil potatoes, the starch granules absorb water and swell in a process called gelatinization. This transformation begins at 140°F (60°C) and completes around 200°F (93°C).

Interestingly, cooling cooked potatoes creates resistant starch—a type that resists digestion and functions like fiber. A study from the National Center for Biotechnology Information found that cooling boiled potatoes for 24 hours increases resistant starch content by up to 70%, potentially reducing the glycemic impact by 25-30%.

Practical Implications for Your Kitchen

Understanding potato starch behavior solves common cooking dilemmas:

- Mashed potatoes: Use high-starch varieties like Russets for fluffy results, while waxy potatoes like Yukon Golds maintain structure for salads

- Frying: Double-frying technique (first at 300°F, then at 375°F) creates crisp exteriors by driving out moisture from starch granules

- Gluten-free baking: Potato starch (not whole potatoes) works as a binder, but requires precise ratios to avoid gummy textures

- Dietary considerations: Cooling potatoes before eating lowers their glycemic index, making them more suitable for blood sugar management

Common Misconceptions About Potatoes and Starch

Many people confuse potatoes with pure starch due to oversimplified nutrition discussions. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics clarifies that potatoes qualify as both a vegetable and a carbohydrate source in dietary guidelines. Unlike refined starch products, whole potatoes deliver potassium (more than bananas), vitamin C, and dietary fiber—especially when eaten with the skin.

When comparing potatoes to other starchy foods, consider these context boundaries:

- For blood sugar management: Cooling potatoes increases resistant starch, lowering glycemic impact

- For athletic performance: Potatoes provide quick energy plus electrolytes lost through sweat

- For weight management: Whole potatoes have high satiety value compared to processed starch products

- For digestive health: Potato fiber and resistant starch feed beneficial gut bacteria

Choosing the Right Potato for Your Needs

Different potato varieties contain varying starch levels that affect their culinary performance:

- High-starch potatoes (Russet, Idaho): Best for baking, mashing, and frying (30-35% starch content)

- Medium-starch potatoes (Yukon Gold): Versatile for most cooking methods (20-25% starch)

- Low-starch/waxy potatoes (Red Bliss, Fingerling): Maintain shape when boiled (15-20% starch)

Storage conditions also affect starch content. The Alberta Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry notes that storing potatoes below 40°F (4°C) converts starch to sugar, causing undesirable sweetness and darkening when fried.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4