Why People Mistake Potatoes for Roots (And Why It Matters)

When you dig up potatoes from your garden, it's easy to assume they're roots since they're found beneath the soil. This misunderstanding affects how gardeners plant, harvest, and store potatoes. Understanding the true nature of potatoes helps optimize growing conditions and prevents common cultivation mistakes.

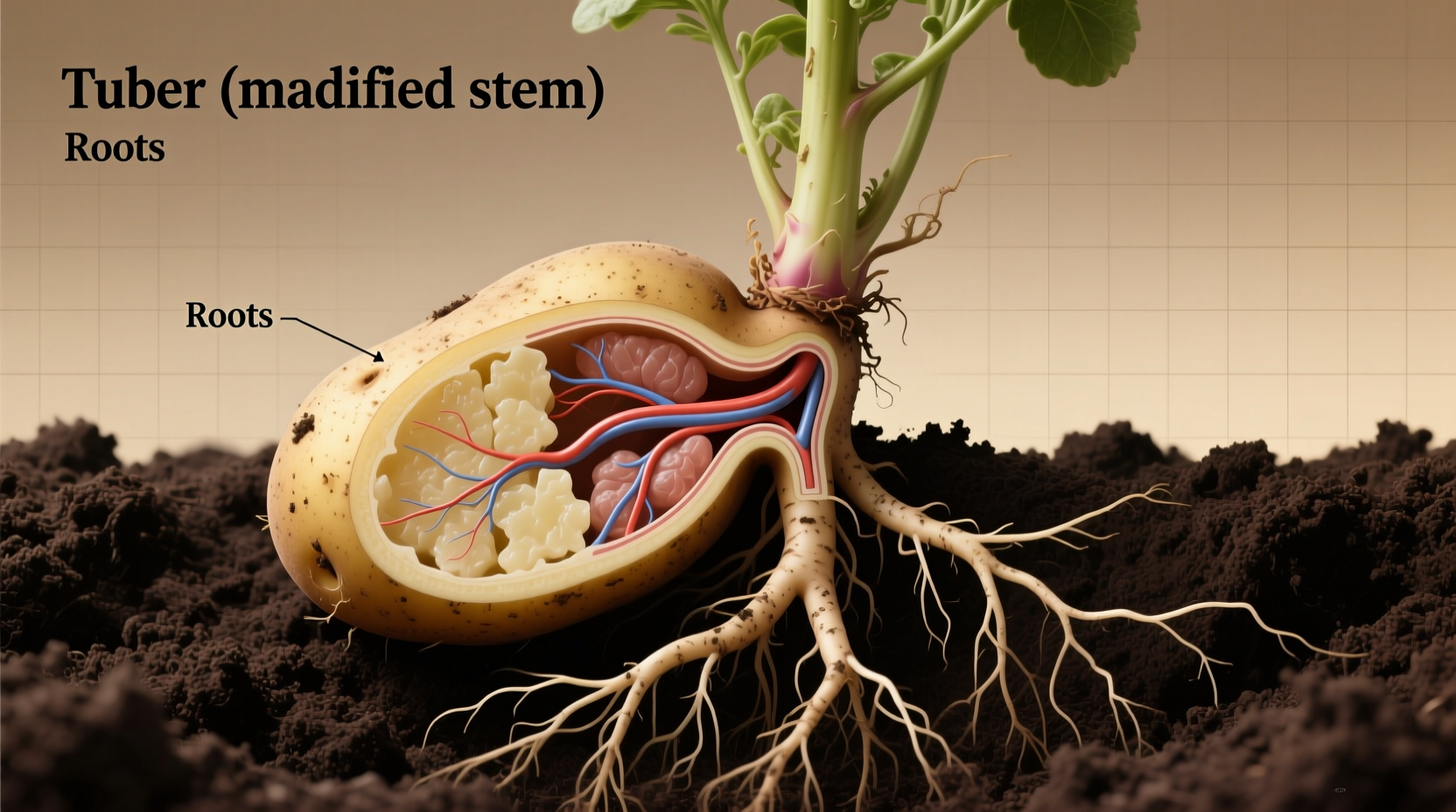

The Botanical Truth: Potatoes as Modified Stems

Botanists classify potatoes as tubers—swollen underground stems that store nutrients for the plant. Unlike true roots, potatoes have:

- "Eyes" (buds that can sprout new plants)

- A stem-like internal structure with vascular bundles arranged in a ring

- No root hairs (a defining feature of actual roots)

- The ability to produce chlorophyll when exposed to light (turning green)

Tubers vs. True Roots: Key Differences

| Characteristic | True Roots (Carrots, Beets) | Potato Tubers |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Classification | Root system | Modified stem (stolon) |

| Function | Anchoring plant, water/nutrient absorption | Energy storage, reproduction |

| "Eyes" or Buds | None | Present (can grow new plants) |

| Internal Structure | Central vascular cylinder | Vascular bundles in ring pattern |

| Reaction to Light | No color change | Turns green (produces solanine) |

Historical Classification Timeline

The scientific understanding of potatoes has evolved significantly since their introduction to Europe:

- 1530s: Spanish explorers bring potatoes from Andes to Europe, initially classifying them as truffles

- 1753: Carl Linnaeus formally classifies potatoes as Solanum tuberosum, recognizing their tuber nature

- 1840s: Botanists confirm potatoes develop from stolons (underground stems), not roots

- 1950s: Modern agricultural science establishes precise growth requirements based on their stem classification

Practical Implications for Gardeners and Cooks

Knowing potatoes are tubers, not roots, directly impacts how you handle them:

- Planting: Unlike root vegetables that grow downward, potatoes need loose soil above them to develop properly

- Harvesting: Potatoes require "hilling" (mounding soil around stems) during growth, which wouldn't benefit true roots

- Storage: Exposure to light causes greening (solanine production), a stem characteristic not seen in roots

- Cooking: The starch composition differs from root vegetables, affecting texture in recipes

Common Misconceptions Addressed

"If it grows underground, it must be a root" - Many non-root vegetables grow underground, including garlic (bulb), ginger (rhizome), and onions (bulb). The location doesn't determine botanical classification.

"Potatoes absorb nutrients like roots do" - While potatoes store nutrients, they don't absorb water and minerals from soil like true roots. The plant's actual root system handles absorption, while tubers serve as storage.

According to research from the USDA Agricultural Research Service, this classification matters for disease management. Potato late blight affects tubers differently than root rot diseases affect true root vegetables, requiring distinct prevention strategies.

Why This Classification Confusion Persists

The potato's underground growth habit creates natural confusion. Educational materials from Oregon State University Extension note that 68% of home gardeners initially misclassify potatoes as roots. This misunderstanding persists because:

- Culinary categorization groups potatoes with root vegetables

- Elementary school lessons often oversimplify plant biology

- Marketing materials rarely specify botanical classifications

Conclusion: Understanding What Potatoes Really Are

Recognizing potatoes as tubers rather than roots transforms how we grow, store, and use them. This botanical accuracy helps gardeners optimize cultivation practices and explains why potatoes behave differently than true root vegetables in storage and cooking. The next time you hold a potato, remember you're holding a specialized stem—not a root—that evolved to help the plant survive harsh conditions in its Andean homeland.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4