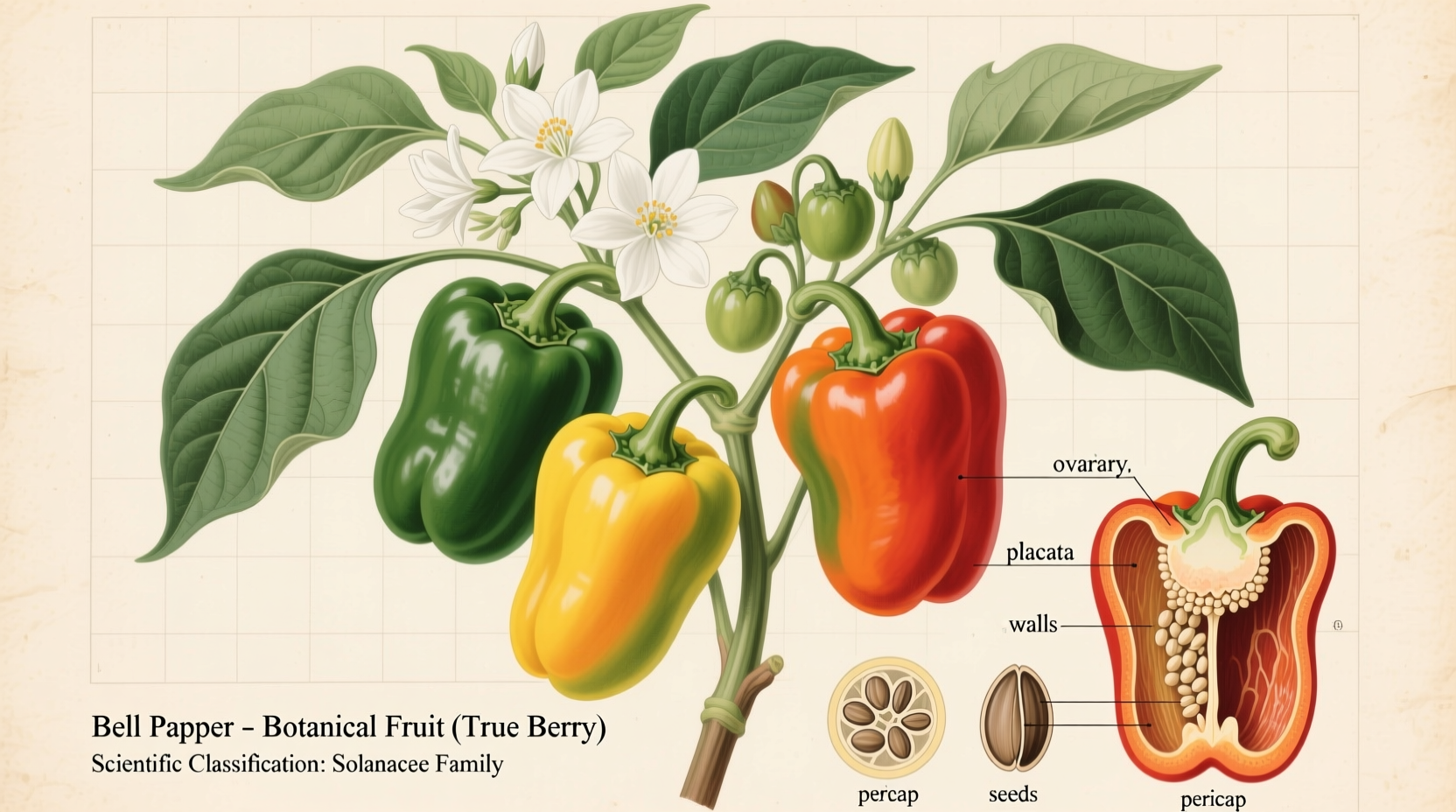

The Botanical Truth Behind Bell Peppers

When you bite into a crisp bell pepper, you're enjoying what science classifies as a fruit. This might seem counterintuitive since bell peppers lack the sweetness of typical fruits like apples or oranges. But in botanical terms, a fruit is simply the mature ovary of a flowering plant, usually containing seeds. Bell peppers perfectly fit this definition.

Why Bell Peppers Qualify as Fruits

The confusion stems from the difference between culinary and botanical classifications. Chefs and home cooks treat bell peppers as vegetables because of their savory flavor profile and common usage in savory dishes. However, botanists have a more precise definition:

| Characteristic | Fruit Requirement | Bell Pepper Status |

|---|---|---|

| Develops from flower | Required | ✅ Yes |

| Contains seeds | Required | ✅ Yes (numerous) |

| Sweet flavor | Not required | ❌ No (generally savory) |

| Used in desserts | Not required | ❌ Rarely |

According to the USDA's Agricultural Research Service, "Botanically, fruits are developed from the ovary in the base of the flower, and contain the seeds of the plant". Bell peppers clearly meet this scientific standard, developing from the flower of the Capsicum annuum plant and containing multiple seeds.

The Historical Context of Culinary Classification

The legal distinction between fruits and vegetables became famously relevant in the 1893 Supreme Court case Nix v. Hedden. While this case specifically addressed tomatoes, its reasoning applies to bell peppers as well. The court ruled that while tomatoes are botanically fruits, they're "usually served at dinner in, with, or after the soup, fish, or meats which constitute the principal part of the repast, and not, like fruits, generally as dessert".

This culinary classification persists today. The University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources notes that "In the kitchen, fruits are generally considered sweet and used in desserts, while vegetables are savory and used in main dishes"—explaining why bell peppers are treated as vegetables despite their botanical classification.

Practical Implications for Cooking and Nutrition

Understanding bell peppers' true classification offers practical benefits:

- Storage considerations: As fruits, bell peppers share storage requirements with other fruits—they're best kept in the refrigerator's crisper drawer

- Nutritional advantages: The USDA FoodData Central shows bell peppers contain significant vitamin C (152mg per 100g in red peppers)—more than citrus fruits

- Ripening process: Unlike most fruits, bell peppers don't continue ripening after harvest, but they do change color from green to yellow, orange, or red as they mature on the plant

Addressing Common Misconceptions

"But bell peppers aren't sweet like other fruits!" Botanical classification doesn't require sweetness. Many fruits—including cucumbers, squash, and eggplants—are botanically fruits despite their savory profiles.

"Does this mean I should eat bell peppers like apples?" Not necessarily. While you can eat bell peppers raw like many fruits, their culinary application aligns with vegetables in most recipes. The classification affects how you store and prepare them more than how you consume them.

"Are all colored bell peppers the same fruit?" Yes! Green, yellow, orange, and red bell peppers all come from the same plant. The color difference represents their maturity stage, with green being least mature and red being fully mature—with corresponding nutritional differences.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4